A Translator, Not an Interpreter Professor Jeff Barnett publishes a translation of Cuban poetry.

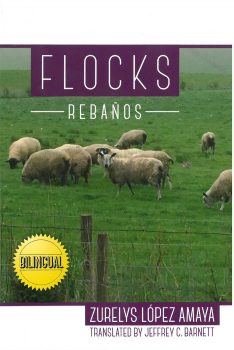

Jeff Barnett, professor of Spanish and head of the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program at Washington and Lee University, has partnered once again with Cubanabooks for his latest work of translation, “Flocks”/“Rebaños” (2017) by Zurelyz López-Amaya.

Although Barnett has worked on translations of other Latin American authors, most recently Uva de Aragón’s “The Memory of Silence”/“Memoria del silencio” (Cubanabooks, 2014) and Carlos Fuentes’ “Litany of an Orchid”/“Letanía de una orquídea” (Exchanges, 2015), this marks his first book-length translation of a poetic work.

“López Amaya is a new voice in Spanish-American literature,” said Barnett. “She was first published in 2010, and I didn’t know anything about her until the editor of Cubanabooks brought her to my attention. After I finished reading ‘Flocks,’ I said, ‘Wait a minute, am I understanding what she’s saying?’ ”

Barnett chose to translate López-Amaya’s poetry because “I thought it was cleverly done. This is a bittersweet love affair with Cuba. It’s a blunt indictment of the system — an attack on the Castro regime — but at the same time displays a nationalistic pride. There’s plenty of literature that attacks Castro, but what was different and enticed me is that this was someone who clearly and deeply loves Cuba but hates what it has become.”

Barnett noted, “Western civilization has always put an emphasis on the pastor of the flock. But here, it’s the flock, not the shepherd, that’s important — it’s the people. Zurelys’ work questions who are we as a flock when we are without a shepherd. It becomes a not-so-thinly veiled metaphor for the allegory for what it’s like to be in a flock when the shepherd has abandoned us, and we are roaming freely. How do I maintain my identity in the flock, how do I recapture that, how do I move the flock along, and what is good for the flock?”

As he started working on “Flocks,” Barnett wrestled with López-Amaya’s “deep imagism,” which was new to him. Her volume consists mostly of prose poetry, with some free verse. Her topics, seemingly mundane objects, such as her desk chair, her garden, a bird that visits her feeder every day, “celebrate the ordinary in order to show us that nothing is insignificant,” said Barnett. “Zurelys’ work is not a lament or an eulogy for Cuba, but is a longing to recognize and recover all that is good.”

Working with poetry was “a whole new ball game for me as a translator,” Barnett said. “With prose, you can navigate through long sentences without people ever hearing your voice. You always have to be true to the author’s voice — the translator should never be an interpreter. With Zurelys’ poetry, I had to be very careful how far I led readers to where I think she wants them to be without hitting them over the head with it.”

As satisfying as this project was, Barnett is looking forward to his next project, which he describes as the opposite end of the spectrum from “Flocks.” This summer he’ll start work on translating another book by Uva de Aragón, about a female Cuban-American detective. “Spanish-American literature has a long tradition of detective fiction, but this is the first one I know of where a female protagonist plays the lead role of detective,” said Barnett. “ ‘Flocks’ took a long time to translate because I had to fight for every word, every line. It was rewarding, but in a different way than translating prose. In a novel, you get to know the characters as they evolve and take on their own life and, after a while, they seemingly tell you what to say.”

If you know any W&L faculty who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

You must be logged in to post a comment.