Recent Gift Illustrates Poet’s ‘Twin Obsessions’ Friends and classmates of Jeanne de Saussure Smith ’08 have dedicated an E. E. Cummings painting to W&L in her memory.

In summer 2018, Washington and Lee University received a generous gift of a painting by Edward Estlin (E. E.) Cummings that was made possible by members of the W&L Class of 2008 in memory of Jeanne de Saussure Smith ’08, a vivacious young woman from Charleston, South Carolina. Jeanne was an English major at W&L, and the painting now hangs in Payne Hall, home of the English Department. Tragically, she died at the age of 22 during her first semester at the University of South Carolina School of Law.

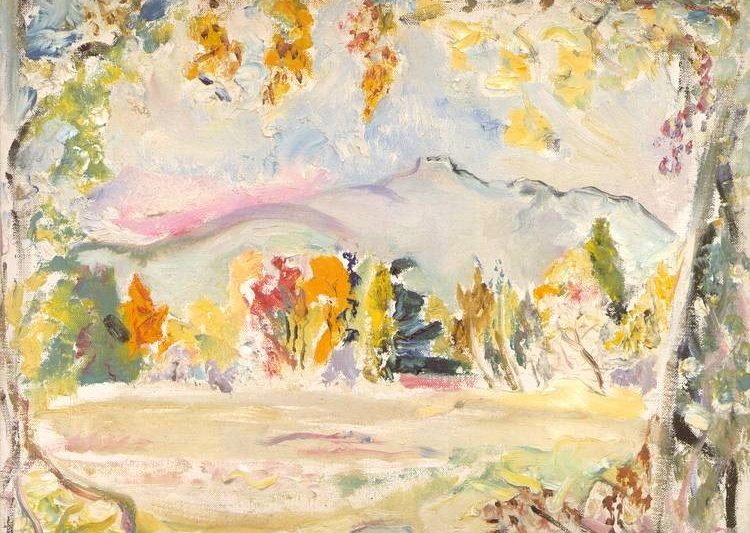

Entitled “Fall Landscape: Chocorua” and composed in 1937, the work is a small oil painting on canvas board that lyrically and exuberantly expresses the landscape Cummings saw near Joy Farm, his family’s summer home in the Silver Lake part of Madison, New Hampshire. In the painting, Mount Chocorua, a summit in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, is centrally depicted in front of Chocoura Lake, which is edged by colorful autumn trees. The entire composition is framed with a fringe of leaves and vegetation. In addition to Cummings, this mountain and lake have inspired many artists over the last two centuries, including Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School; watercolorist John Marin; Frank Stella, proponent of 20th century hard edge abstraction; and contemporary New England artist Eric Aho.

E. E. Cummings is best known as a 20th century avant garde poet who created a distinctive personal style of writing by boldly experimenting with form, syntax, punctuation and spelling. Praised as one of the most innovative poets of his time, Cummings was also a self-taught visual artist who considered writing and painting his “twin obsessions.” His contemporaries reported that he actually painted more than he wrote.

As a mature writer, Cummings divided his time between Greenwich Village in New York and Joy Farm, in addition to traveling abroad when possible. He was introduced to Paris in 1917, when he volunteered for service in the Ambulance Corps after receiving his B.A. and M.A. from Harvard University. Cummings was sent to France, where he ended up in a prisoner-of-war camp on suspicion of espionage because of his anti-war grumblings and writings. His three-and-a-half-month stint became fodder for his 1922 publication, “The Enormous Room.”

After WWI, Cummings returned to his beloved Paris to live for several years. There, he was friends with writers Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, and attended parties with F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Cole Porter, Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein, in whose house hung works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cezanne and other leading artists of the early 20th century. At the time, Paris fomented with avant garde art movements, including Dadaism, Surrealism, Cubism and Fauvism, and young artists of all types were caught in the throes of intellectual stimulation.

Cummings both wrote and painted daily, responding to his surrounding environment. He painted street scenes as well as abstract works that reflected the influence of Post-Impressionists like Cezanne and Fauves like Henri Matisse, both of whose paintings vibrated with color and atmosphere. Cubism influenced Cummings’ writing, and he broke down forms and reassembled poetic elements much as Picasso and Braque had done with objects and figures a decade earlier in painting. Charles Riley, author of “The Jazz Age in France,” describes Cummings’ paintings of the 1920s as “…dashed on the canvas with a jaunty busy brush that never labors, never hesitates. They are so fast and vivacious that they blur in just the Modernist way his poetry does.” At the time, Cummings’ abstract works were widely acclaimed and his drawings were published in the Modernist journal, “The Dial.”

After 1928 and for the rest of his life, E. E. Cummings painted representationally, focusing on portraits, still lifes, figures and landscapes like “Fall Landscape: Chocorua.” His paintings became increasingly personal, bursting with exuberant color. Cummings also wrote extensively about visual art, color theory and aesthetics, but mostly in unpublished notes.

However, in 1945, just after his 50th birthday, Cummings wrote a foreword to a catalog for a one-man exhibition of his work at the Memorial Gallery in Rochester, New York, that included a prose poem written in the form of a question-and-answer interview with a painter. The same piece was later published in 1965 in a small book titled “E.E. Cummings: A Miscellany Revised,” now out of print, in which Cummings wrote his ideas on what it means to be an artist. Essentially, he saw absolutely no difference between being a poet and a painter.

Cummings is not unique in being both a visual artist and a writer. John Dos Passos, Cummings’ Harvard classmate and friend in France, was a novelist and a painter, as well as a playwright. Other notable writers who painted or drew included William Blake, George Sand, William Carlos Williams, Henry Miller, Mark Strand, Sylvia Plath, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac and Kurt Vonnegut, among many others. Poets and writers also have influenced visual artists. Soon, a print by 20th century artist Grace Hartigan will hang in Payne Hall along with Cummings’ work. Hartigan’s 1960 lithograph, entitled “The Hero Leaves His Ship,” was inspired by a poem of the same name by New York School poet Barbara Guest.

E.E. Cummings died in 1962, at which time his wife, Marion, inherited all of his artwork of approximately 1,600 drawings and paintings. After her death, their daughter, Nancy Cummings Andrews, inherited the works and donated them as a means of fundraising to the Luethi-Peterson Camps, a nonprofit organization that operated summer camps for children for the promotion of international understanding, one of them close to the Cummings summer home in New Hampshire. Over time, the collection has been sold to museums and private collectors.

A decade after Jeanne Smith’s death, her W&L classmates, led by Dargan Rain ’08 and her husband, Rob Rain ’07, wished to honor her memory at their 10th Class Reunion. Jeanne’s parents, Margaret Rinehart Smith and Park B. Smith Jr., suggested the friends raise money for a gift of art to hang, if possible, in Payne Hall for the English Department. Dargan Rain first contacted the Development Office and then approached me, as curator of the university’s art collection, for guidance in finding and choosing an appropriate work of art.

Early in the process, Margaret Smith told me of a landscape of the Cotswolds in the English Department that was dedicated to Carlton Davies “Bubba” Walker ’80, an old friend of her husband’s. “We drop by to see it when we visit the campus. It reminds us that Bubba Walker dearly loved his time there, and his time at the school.”

After much research, thought and discussion with Dean Suzanne Keen before her departure, I suggested purchasing a painting by Cummings, whose estate is handled by Ken Lopez Bookseller in Hadley, Massachusetts. Jeanne’s mother, who had just read a section of her daughter’s journal that quoted Cummings’ poem, “i carry your heart with me,” was thrilled by the idea. It seemed like serendipity.

At Margaret Smith’s request, Jeanne’s friends chose three Cummings paintings that they believed reflected the feeling of the poem, and that Jeanne would also have liked. I made the final selection and submitted an acquisition proposal to the Collections Committee, which supported the purchase of the painting, made possible by a gift of funds from 17 of Jeanne’s classmates.

The painting has since been newly framed and installed in Payne Hall, where it immediately generated interest among faculty and students. A dedication ceremony planned for Young Alumni Weekend in September was cancelled because of Hurricane Florence, but I sent photographs of the painting to the Smiths and to Dargan Rain. Rain responded, “We have been so touched by the university and your thoughtfulness to this dedication. It has turned out better than we could have dreamed or imagined.”

“It is our hope,” wrote Margaret Smith, “that returning students will visit the painting and be encouraged to hold their memories of their time in Lexington (and perhaps Jeanne) in their hearts.”

Poems by E. E. Cummings

Jeanne de Saussure Smith’s mother found the following Cumming’s poem in her daughter’s journal after she passed away.

[i carry your heart with me(i carry it in]

i carry your heart with me(i carry it in

my heart)i am never without it(anywhere

i go you go,my dear;and whatever is done

by only me is your doing,my darling)

i fear

no fate(for you are my fate,my sweet)i want

no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true)

and it’s you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life;which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that’s keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart(i carry it in my heart)

The following untitled Cummings poem, written in the form of a Q&A with a painter, was published in 1965 in a small book titled “E. E. Cummings: A Miscellany Revised,” now out of print.

Why do you paint?

For exactly the same reason I breathe.

That’s not an answer.

There isn’t any answer.

How long hasn’t there been any answer?

As long as I can remember.

And how long have you written?

As long as I can remember.

I mean poetry.

So do I.

Tell me, doesn’t your painting interfere with your writing?

Quite the contrary: they love each other dearly.

They’re very different.

Very: one is painting and one is writing.

But your poems are rather hard to understand, whereas your paintings are so easy.

Easy?

Of course — you paint flowers and girls and sunsets; things that everybody understands.

I never met him.

Who?

Everybody.

Did you ever hear of nonrepresentational painting?

I am.

Pardon me?

I am a painter, and painting is nonrepresentational.

Not all painting.

No: housepainting is representational.

And what does a housepainter represent?

Ten dollars an hour.

In other words, you don’t want to be serious —

It takes two to be serious.

Well, let me see… oh, yes, one more question: where will you live after this war is over?

In China; as usual.

China?

Of course.

Whereabouts in China?

Where a painter is a poet.

“Fall Landscape: Chocorua”

“Fall Landscape: Chocorua”

You must be logged in to post a comment.