A 345-Year-Old Bestseller “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China" tells the story of a trade delegation sent from the Dutch East India Company to China in 1655-57.

Today, if you want to learn about China, you have many choices; a Google search yields 135,000,000 hits in less than a second, and if you want a hard copy, Leyburn Library at Washington and Lee has over 9,000 books on the subject. In the 17th century, your choices were far more limited. This book, “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China,” was one of the few available, and was considered by many to be the best.

It is actually an English translation of Johan Nieuhof’s “Het Gezandtschap der Neêrlandtsche Oost-Indische Compagnie, aan den grooten Tartarischen Cham, den tegenwoordigen Keizer van China.” First published in the Netherlands in 1665, it is an account of a trade delegation sent from the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (the Dutch East India Company) to Shunzhi, the emperor of China, in 1655-57.

The Dutch East India Company, which was often known by its initials VOC, had been founded in 1602 and had a monopoly on Dutch trade with Asia (which in 17th-century Europe was known as “the Indies”). One of the first joint-stock companies in existence, the VOC helped create the modern global economy, building a trade network that linked Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and the Americas. It also helped popularize and commercialize a wide range of Asian products, such as spices, silk, cotton, porcelain and tea, to European and American consumers.

The company had been acquiring Chinese goods via Chinese traders who brought them to VOC trading settlements in Taiwan and Indonesia, but wanted direct access to China itself. Eschewing violence and intimidation (tactics they used often to force trading concessions in other parts of Asia), they opted for negotiation, and sent a trade delegation, or “embassy,” as they referred to it, to Beijing.

The delegation was led by two merchants, Pieter de Goyer and Jacob Keijser, who were accompanied by four other merchants, six servants, a surgeon, a steward, a drummer and trumpeter, the last two no doubt to assist in making a grand entrance. The trip from the Dutch settlement of Batavia in Indonesia to Beijing and back took almost two years. Diplomatically and economically it was not a success; the Chinese refused to allow Dutch merchants to trade in Chinese ports. It did, however, lead to the production of this book, which was written by the delegation’s steward, Johan Nieuhof (1618-1672).

Nieuhof, who had previously worked for the Dutch West Indian Company in Brazil, was instructed to make a written and pictorial record of the delegation’s trip through China. He saw it as an “opportunity to make a more exact Discovery of the Genius and Manners of the People, and Customs of the Place, and Countrys supposed by all Geographers to be the richest in the World.”

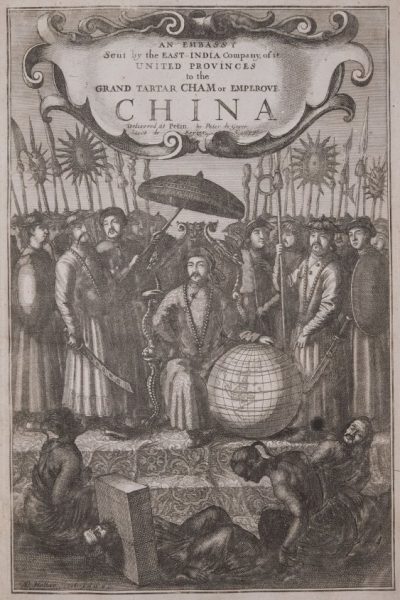

In addition to 431 pages of text that touched on China’s geography, government, religion, economy and history, the book was illustrated with over 150 engravings “taken from life” that provided “accurate Maps and Sketches, not only of the Countreys and Towns, but also of Beasts, Birds, Fishes, and Plants.” Among the illustrations were depictions of Chinese cities like the port of Guangzhou and the capital, Beijing; monuments like the porcelain pagoda at Nanjing and the Great Wall (which he did not actually see); and one of the earliest depictions of a tea plant to be published in Europe.

Though Nieuhof claimed that he had provided “an accurate description of the Chinese cities, villages, government, sciences, crafts, customs, religions, buildings, costumes, ships, mountains, crops, animals etc…,” in reality his observations were combined with accounts by earlier European missionaries. Many of the illustrations were embellished with people, animals and ships to make the scenes more exotic and visually appealing than his original on-site sketches.

Despite these flaws, Nieuhof’s “Embassy” was one of the most comprehensive, accurate and lavishly illustrated books on China published in 17th-century Europe. It was a bestseller, going through 14 editions in five languages (Dutch, French, German, English and Latin) by 1700, and was avidly read by merchants, armchair travelers and manufacturers, who mined its illustrations for designs for paintings, textiles, silver, and ceramics.

The original edition was translated, or “English’d,” as the title page attests, from the Dutch by the London-based cartographer and publisher John Ogilby (1600-1676) in 1669. Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), a Prague-born etcher who worked in London, copied the illustrations. The English translation proved so popular that a second edition, of which this book is an example, was published in 1673.

This particular copy is inscribed on the flyleaf “Mary Curtis 1911.” This is probably the Mary Curtis born in 1878 (date of death unknown). She was the sister of Francis Gardner Curtis (1868-1915), a painter, Asian scholar and curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in the early 20th century. Mary shared her brother’s interest in Asia. From her, the book passed to her niece, Helen Coolidge, and from her to her son, Francis Coolidge. It was gifted to the Reeves Center in his honor by his wife, Marylouise, and their two daughters, Lucy Coolidge and Georgina Coolidge ’08.

Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China.”

Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China.” Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China,”

Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China,” Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China,”

Illustration from “An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces to the Grand Tartar Cham Emperor of China,”

You must be logged in to post a comment.