Alumni Weigh in on Vietnam Anniversary Alumni who served react to the Fall 2017 alumni magazine article about the war, and share some of their thoughts about that time.

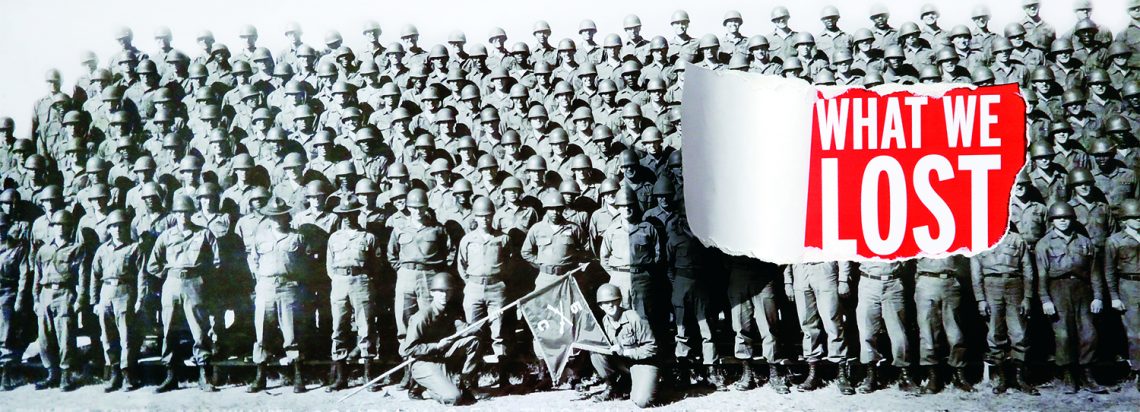

The following correspondence was received by W&L: The Washington and Lee Magazine following publication of “What We Lost: Vietnam 50 Years Later,” which appeared in the Fall 2017 issue.

From Richard Coplan ’64:

I was one of three men in my fraternity at Washington and Lee who went through R.O.T.C. In the ’60s the W&L campus was remarkably quiet. I did not get a sense of the unrest that swept the nation, but perhaps we were a bit early. I volunteered for a program that sent me directly to my active-duty unit without the benefit of branch training. I also wanted to be in a combat arm (infantry, armor or artillery), and volunteered for Vietnam.

Eleven days after graduation in 1964, I was a second lieutenant in the 92nd Artillery, Fort Hood, Texas. The other ROTC men in my fraternity, Jim Wallenstein and David Hyman, served in Vietnam with honor.

Finally, after almost a year of training, our entire unit was scheduled to ship out. Seventy-two hours before, I had been sent to battalion headquarters and told that either I or the other lieutenant in my battery would be going to Fort Sill to teach gunnery. What did I prefer? I honestly didn’t have an answer. The other officer, Lt. Tom Reynolds, said Vietnam.

Three days later, the entire unit was sent to Vietnam and I was on my way to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. It was quite an opportunity. I was in a major’s slot and my boss was a one-star general. Unfortunately, at that time we were sending 200 soldiers a week to Vietnam right from basic training.

My unit was not so lucky. Self-propelled 155m howitzers are heavier than tanks. Fifty years ago they could shoot over eight miles with amazing accuracy, but the terrain was impossible. They couldn’t maneuver. The tracks would embed in the muck. As a result, my unit had to be supported by infantry because the guns simply couldn’t move around, and they had to resort to what was called “direct fire.” They should never have sent these guns into that terrain, but as a result, there were heavy casualties.

I never went to Vietnam, but I lost many friends from the unit. It took years for me to be able to visit the Vietnam Memorial. I was angry, and furious at our leaders. With the benefit of hindsight, from McNamara’s book to the amazing new Ken Burns documentary of the entire war, we can now see how all in power, especially LBJ, got it wrong. Their folly cost us over 58,000 lives.

It remains a sad time in American history.

From Bruce W. Rider ’66:

Thank you for including me in Lindsey Nair’s excellent article, “What We Lost,” about W&L graduates serving during the Vietnam War.

What we gained was a lifelong dedication to building peaceful institutions after our military service, bolstered by the examples of both George Washington and Robert E. Lee, who turned away from the dark heart of war to create frameworks for government and education girded by honor and integrity.

The exciting new look and feel of the magazine still includes obituaries of the 1930s and ’40s graduates, many if not most of whom, like my father (Cowl Rider ’37) served in World War II (as did the remarkable philosophy professor, Harrison J. Pemberton, whose recent passing was reported in this issue).

Washington and Lee University has honored its namesakes by sending some to war but leading all to lives of civic participation and meaningful service.

From Donald B. McFall ’64, ’69L:

I served for two years as an officer in the United States Army in the mid-1960s. I was lucky in that I did not have to serve in Vietnam. Instead, after attending the Field Artillery Officer Basic Course at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, I spent about three or four months in an infantry division in West Germany. I was stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, for the rest of my tour.

Fort Campbell was the home of the 101st Airborne Division, and the division, at that time, had one brigade (about 2,000+ troops) serving in Vietnam. I was lucky enough to serve on the Special Staff of the Commanding General of the 101st Airborne Division and Fort Campbell. One of the duties I had was to represent Major General Barsanti at funerals of soldiers killed in Vietnam when he could not attend the funerals.

You have never had your heart broken until you attend a funeral for a young soldier who died far from home — and often alone. Many times, there would be a young widow, lost and alone, with one or two children in her arms.

The boys who served never got the respect and attention they deserved, so that is why what you are doing to honor them means so much to me and others like me. It is not too late for W&L to say “Welcome Home” to the ones who served in Vietnam, and “Thank You” to others who spent two years or more in the service of our country.

From Charlie Tomm ’68:

1968 was indeed a complex time, and a period I have intentionally avoided contemplating. Doing so is like opening a troubling time capsule, as there was much looming ahead.

However, there was never any doubt in my mind about entering the military after graduation from Washington and Lee, at least partly because of the examples set by members of my family. My father was a widower with an infant daughter and exempt from military service in World War II. Nevertheless, he entered the Navy, left his daughter in the care of his parents and made 16 crossings of the North Atlantic.

My great uncle was exempt due to age, but became an Army medic, spent two years on various fronts in Europe and received two Purple Hearts. My uncle was a P-51 pilot who died two weeks before Japan surrendered. My grandparents grieved every day for the remainder of their lives.

One recollection is thinking of Vietnam as our generation’s war, just as almost every prior generation seemed to have one. At the time I viewed military service as a duty to fulfill, and that sentiment remains. Other memories are not nearly as sanguine, such as the spring ’67 death of my Western PA friend and teammate, Marine 2nd Lt. Jack Kelly ’66. His loss caused some pause in my thoughts.

With the passage of summer, my thoughts eased. In the fall of ’67, I took the oath to enter Navy OCS and volunteered every time there was an opportunity. My four years of active duty service provided many lessons on the crucial roles of self-discipline and teamwork, as well as the critical importance of focusing upon details. Those lessons continue to be invaluable in my personal life and work endeavors.

Fifteen months after graduation from W&L, I was 12,000 miles away as a diver and officer for almost two years on the Navy’s only troop-carrying submarine, which was an experimental diving unit built inside of a submarine. We drilled constantly and engaged in few actual operations.

Most would view us as being among the fortunate. But we felt guilty for not doing more to contribute to the war effort, especially when a couple of our diving unit buddies were wounded in other operations. This caused additional pause for thought, as did daily news of numerous casualties. However, the worries of those back home who cared about us were much greater than our own, because we were well-trained to react and adapt quickly to our situations.

Returning to the U.S. in the summer of ’71 for my final year in the Navy was a befuddling experience. Anti-war sentiment was rampant and reported daily in the media. It was also expressed in many protest songs that I largely tuned out, although “Bring the Boys Home” by Freda Payne in ’71 remains quite poignant.

Some parts of the country were markedly different than before. On a visit to a friend in Boston, I was called names and cursed, and almost permitted myself to be goaded into a fight. Some were spat upon.

I entered W&L Law School in the fall of ’72. A first-year law school classmate who attended a Northeast college actually told me those of us who served in the military were dumb to do so, which kindled a violent reaction. He avoided me for the balance of law school. Many politicians, academics and entertainers actively encouraged the anti-war sentiment, and even advocated poor treatment of the military. To this day, I cannot comprehend why we were treated so poorly for fulfilling our perceived duties.

It is shameful that our politicians and diplomats mishandled the war so egregiously. At the same time, the media sought fresh headlines every day and seemed largely disinterested in the enemy’s treatment of the Vietnam populace and American POWs.

We were completely puzzled as to why the war was being fought with no apparent intent to win, and with nothing positive ever reported in the media. The lack of a will to win wasted many lives. It greatly increased the pain of those who lost loved ones or must continue to live with lifelong disabilities.

I will never understand!

From Rev. Tom Crenshaw ’65:

I read with great interest the article “What We Lost.” I was particularly interested in the comments from Dr. William Sledge and Jim Oran, who were two classes behind me and members of the football team. In 1962, I transferred from Virginia Military Institute to Washington and Lee, where I was captain of the baseball team and co-captain of the football team. I was president of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and we would often visit area orphanages and nursing homes. I worshiped at the First Presbyterian Church in Lexington.

I graduated in 1965 and headed off to Princeton Seminary, where I earned a bachelor of divinity degree in 1968. During my second year at seminary, I became concerned about the nature of the Vietnam War, and like many others, I was significantly impacted by the television picture of the street execution of that unarmed Viet Cong soldier.

While my dad had been a colonel in the military, and while I had always considered myself a strong supporter of the military, my attitude drastically changed as I continued to read more and more about the war. Unlike many young men my age who were being drafted into service, I was protected by my seminary exemption status, something that I felt was unfair. At a worship service, I turned in my draft card as a way of protesting my exemption, and in doing so I voluntarily put myself in the same status as most other young men who were unprotected by any exemption they may have been granted.

Over the course of a couple of years, my draft board in Watertown, New York, called me in to determine how to respond to my action. I met with them a number of times, but they seemed unsure how to address my decision. They presented me with a number of questions about how I might have responded to past wars to determine if I could be declared a conscientious objector. I answered that I did not know what I would have done had I been faced with a decision to be involved in the War of 1812, World War I or II, or the Korean War, but I knew I was opposed to this one particular war. Because of my limited objection to a particular war and not all wars, they could not classify me as a conscientious objector who was opposed to all wars. The meetings dragged on for over two years, and while no decision was ever communicated to me, I never heard from them again.

Today I honor and respect all of those who did go and fight. I am a strong supporter of our military and am grateful for their willingness to serve and to protect our freedoms. However, watching the “Vietnam” series by Ken Burns, I feel to some degree vindicated for the position I took. However, having said this, I regret the many lives that were lost during that war, and the grief and suffering so many families endured as a consequence of the war.

During my time in seminary, I spoke in a number of churches whose members were curious as to why I took the position I did. I was a conservative, evangelical Christian, far different from many of my more liberal counterparts who were protesting the war, and it was hard for them to understand why I had taken the position I did.

From Kevin R. Rardin ’84L:

I greatly appreciated the thoughtful and well-written article in the Fall W&L magazine about the graduates who served in Vietnam. I could appreciate many of their thoughts and feelings. I also served in a war.

From 2007 to 2008, I served a year on active duty as U.S. Army judge advocate in Afghanistan. Of course, my experiences were different. I was a 50-year-old lawyer in a war that has not divided our country the way Vietnam did. Still, some things seem the same: the sense of being transformed by the experience, a certain amount of both guilt and gratitude for being alive, and a desire to make one’s life count.

Thank you for writing about these men. They deserve the recognition. They make me proud to be a W&L graduate.

If you know any W&L alumni who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.