Art That Talks Theater students at W&L were challenged to select a piece from the university's art collection and give it voice.

In late October, I gave a special curator’s tour to a Fall Term Acting I class to help Associate Professor of Acting and Directing Jemma Levy introduce her students to their individual end-of-term projects involving works in the university’s art collection. Levy, in planning this assignment, was inspired by the “Talking Statues” project that began in Copenhagen in 2013 and quickly spread throughout the world. Authors wrote dialogue for select statues —mostly cultural figures — and actors gave them voice. Using a smartphone and a QR code located on a traditional identification label, visitors can now connect with the statue, who “calls” the person, and learn about their history. There is also “an app for that.”

Historical information and absolute accuracy are not motivations for this particular theater class project, however. The primary purpose is to give the Acting I students experience in writing and voicing dialogue. The artwork provides inspiration. Twelve students each selected a painting, print or sculpture from among many displayed across campus. My role was to share my curatorial knowledge about these works during a 45-minute socially distanced, mask-wearing sprint across campus to where the works are displayed, ranging from Wilson Hall to Leyburn Library and, finally, to Tucker Hall.

We had fun as we all looked quickly at each of the works to get a sense of the overall composition and superficial content. I then inquired about the reasons for their particular selections. All had a connection with either the work itself or the subject matter, some having personal associations with the characters, and some because the work or subject related to a course they took. We chatted about how just a bit deeper research could make their initial interpretation of the work shift in new directions that might be of interest to the story they would write. I shared with them brief backgrounds about the artists, the subject matter and the time period in which the works were made, hoping to spark some investigations. I trust the students all went away with an eagerness to delve below the surface and think about more complex and nuanced information to inform their creative monologues.

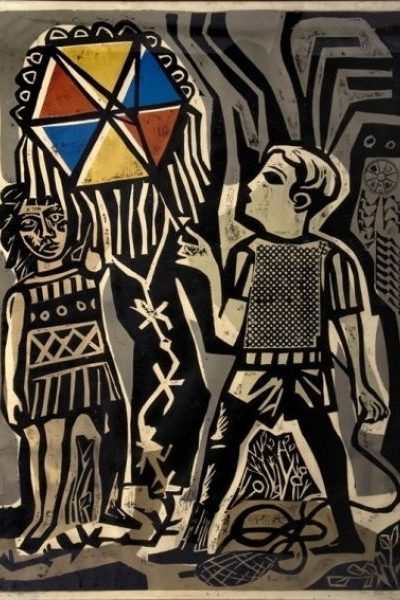

Two works especially provoked me to consider the gap between the students’ collective first impression of an artwork and the artist’s layered subject matter. One is a print by the ground-breaking Latin American artist Antonio Berni (1905 – 1981). The students described the very large woodcut titled “Juanito remontado un barrilete” (Juanito flying a kite), as a depiction of children having fun with a colorful hexagonal kite with streamers on a windy summer day. That indeed is true, and that may be the story that the student ultimately chooses to write and voice for one of the figures.

However, with just a bit of research, one learns that Berni, after studying in France and painting as a surrealist, became the founder of the Nuevo Realismo movement in Argentina that highlighted social injustices in his native country. Our woodcut is related to this movement. In the late 1950s, he created a social narrative with two archetypal characters who populated his most significant work. Juanito Laguna is an impoverished boy from the villas miseria, or shanty towns, of Buenos Aires, and he is the boy who holds the kite in this print. Ramona Montiel is a young girl born of the streets who becomes a prostitute in order to survive. For 20 years, Berni told their stories and revealed the economic and political problems of Argentina not only in prints and paintings, but also in assemblages constructed of trash and discards of daily life. His two fictional figures became popular folk heroes in modern Argentina, eliciting poems and songs to be composed about them. This large print, also called a xylograph — a woodcut in high relief that often incorporates collage elements — is among the earliest examples of Berni’s Juanito and Ramona works. Created in 1962, it is the fourth print in a small series of only 10. That same year, Berni received first prize in printmaking at the 31st Venice Biennale.

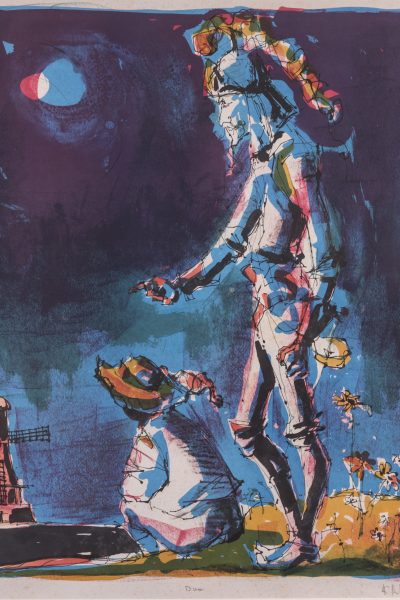

Another print selected by a student that I thought more about is titled “Duo,” and it depicts an image of a knight with a short companion who points to a windmill. Sound familiar? The lithograph is by Alvin Carl Hollingsworth, a leading African-American artist and educator who began his career as a comic book illustrator. He is notable for being a member of the Spiral Group, a coalition of Black artists brought together by Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis in response to the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom planned for August 1963. In the 1970s, Hollingsworth painted wall murals for the Don Quixote Apartment Building in the Bronx in New York City, and for over a decade, he created a series of lithographs and paintings that depicted Cervantes’ characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. The series began about the time the musical “Man of La Mancha” opened on Broadway in 1965. Indeed, that may have been the inspiration for these works, rather than Cervantes’ book.

I am anxious to see and hear what the students do with all of the works selected from W&L museums’ art collection. In addition to Berni’s woodcut and Hollingsworth’s color lithograph, students selected portraits, including a ca. 1865 etching of the French poet Baudelaire by his friend Edouard Manet, a late 19th century lithograph of French singer and comedian Poulin caught onstage by artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and a screenprint of Queen Ntombi Twala of Swaziland that is part of Andy Warhol’s 1985 series titled “Reigning Queens.” Two students selected 19th century sculptures: a bronze copy of the Roman “Dancing Faun of Pompeii” and a wooden carving of the Japanese deity “Daikoku.” Others selected paintings with stories rooted in mythology and the Bible, and still others chose works depicting musicians and bibliophiles.

The mission of the Museums at W&L is to advance learning through direct engagement with collections, to stimulate appreciation of global cultures, and to inspire leadership in the arts and sciences. Working with classes like Acting I in the Theater, Dance, and Film Studies Department allows museum staff to do just that. If this project is successful, then with a little technological assistance, we may actually end up with some artwork that talks.

“Juanito remontado un barrilete” (“Juanito flying a kite”), 1962 Antonio Berni (Argentinean, 1905 – 1981).

“Juanito remontado un barrilete” (“Juanito flying a kite”), 1962 Antonio Berni (Argentinean, 1905 – 1981). “Duo,” from the Don Quixote Series, ca. 1979. Alvin Carl Hollingsworth (1928-2000)

“Duo,” from the Don Quixote Series, ca. 1979. Alvin Carl Hollingsworth (1928-2000)

You must be logged in to post a comment.