Chronicles: The Play’s the Thing The Armadillo has gone down in lacrosse history books as a game-changer.

Google “The Armadillo Play,” and you’ll find several grainy black-and-white YouTube videos of the most unusual athletic contest in Washington and Lee history. “Unusual” is one way to describe the lacrosse match between the Generals and the University of North Carolina on April 24, 1982. It’s been called other things. Embarrassing. Brilliant. Infamous. Historic.

“Rather outlandish” is the phrase favored by Jack Emmer, the Hall of Fame coach who masterminded the formation in an audacious attempt to upset the No. 1-ranked Tar Heels.

Going into the game, odds of an upset were steep. W&L had stopped awarding athletic scholarships in 1954 but competed in lacrosse against scholarship programs in the NCAA’s Division I until joining non-scholarship Division III in 1987.

Despite the clear disadvantage, the Generals had been more than holding their own, making seven straight trips to the NCAA DI tournament from 1972 to 1978.

By 1982, though, the imbalance was increasingly apparent. The week before the North Carolina game, W&L was beaten badly by Virginia. And the Tar Heels were the defending national champions and winners of 19 straight games.

“We had a solid team but not nearly up to what Carolina was putting on the field. We had to find a way to stay close and maybe win at the end,” says Emmer, who coached W&L for 11 seasons (1973-1983) before going to Army where he was the nation’s winningest college lacrosse coach when he retired in 2005.

So, Emmer dreamed up a drastic scheme to keep the ball away from North Carolina’s vaunted offense. He created a formation with one player cradling the ball in a sawed-off goalie stick with a huge pocket encircled by five teammates with their arms locked to form a human shell — hence the aptly named Armadillo. Emmer figured the Armadillo could not only keep the score close but also frustrate the Tar Heels. He was right on both counts.

As chairman of the national rules committee, Emmer knew his plan was legal. To be certain, he checked with game officials in advance.

“I wasn’t going to do it if it was illegal,” Emmer says.

What would his players and coaches think, though?

“Chuck O’Connell, my assistant coach, is a traditionalist, whereas I was something of a renegade. I had to get him on board,” Emmer says. “Then I had to sell the players. Our kids were used to competing, not standing still.”

Phil Aiken ’84 had mixed emotions.

“I thought it was technically legal but not the most sporting approach,” says Aiken, a goalie who produced one of the game’s most dramatic moments. “But we all went with the tactic.”

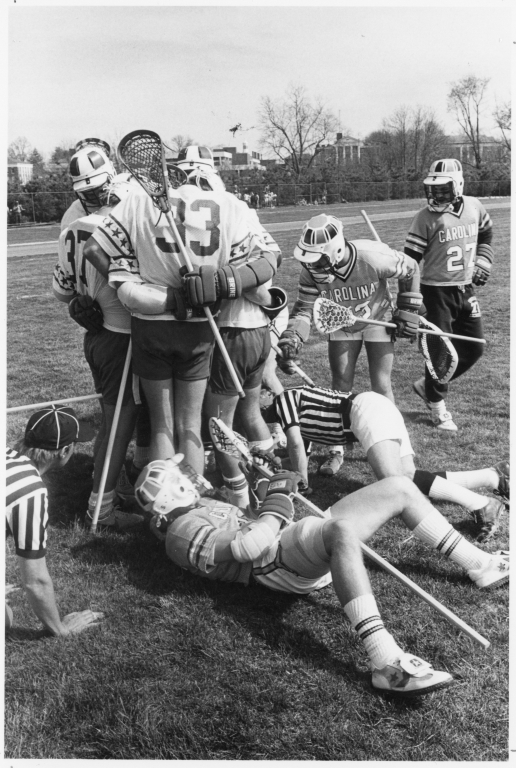

When the Armadillo was unleashed in the first quarter, no one knew what was happening, least of all the stunned Tar Heels.

W&L employed the Armadillo for about 25 of the contest’s 60 minutes. The game got progressively more physical as Carolina’s players tried to dislodge the ball by using their sticks to prod and pummel W&L players from behind, above and even below the Armadillo. The trash-talking accelerated, too.

“In the end, Carolina got frustrated, as you might expect,” Emmer says. “I was concerned our guys might get hurt. For a game where there wasn’t much action, there was a lot of tension.”

Carolina led 5-4 late in the second quarter when goalie Aiken came up with his highlight.

“We were in the Armadillo just behind Carolina’s goal when the rawhide in the pocket of the shortened goalie stick broke, and the ball plopped onto the ground,” Emmer says. “Carolina picked the ball up and rushed toward our goal.”

Since only one goalie stick could be on the field at a time, Aiken was wielding a smaller attackman’s stick as the Tar Heels bore down on him.

“When I was a kid, my dad had me play goalie with an attack stick as a training exercise,” Aiken says. “If you can stop the ball with a small stick, you can stop it with the bigger one.”

And stop it, Aiken did. His save sent W&L fans into a frenzy and kept the Generals within a goal at the half.

Using the Armadillo to stay close, W&L was tied 7-7 early in the fourth quarter, but Carolina made three straight goals to win it 11-8.

The game sent shockwaves through the lacrosse world. Within 48 hours, the rules committee squashed the Armadillo by clarifying the rule on withholding the ball.

“I was glad they outlawed it — and quickly,” Emmer says. “I didn’t want to be responsible for anyone else doing it.”

Outlawed perhaps, but never forgotten. More than four decades later, Aiken says that when the subject of lacrosse comes up, people usually have heard of the Armadillo game.

“Some may still look at it with disdain,” he says, “but I like being part of the lore.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of W&L: The Washington and Lee Magazine.

Photo by Patrick Hinely ’73

Photo by Patrick Hinely ’73

You must be logged in to post a comment.