Dreaming of Freedom Washington and Lee Spanish professor Seth Michelson has compiled a book of poems written by incarcerated undocumented teens and translated by some of his students and him.

To the average American teen, poetry may seem like a scourge.

To the undocumented teenagers incarcerated in a maximum-security facility in Virginia, with no family to comfort them, no lawyers to advise them and little hope that their dreams will ever be more than imaginings, poetry is a speck of light in an otherwise dark existence.

Washington and Lee University Spanish professor Seth Michelson knows this because he has spent the past two years as a volunteer leading poetry workshops at this detention center, where teens are held in isolation cells. During Fall Term 2016, he taught a class, Poetry and the Politics of Immigration, which allowed residents to work one-on-one with W&L students who translated their writings.

As a result of his volunteer work, Michelson compiled “Dreaming America: Voices of Undocumented Youth in Maximum-Security Detention,” a collection of poetry and prose written by undocumented teens. Sales of the book, which was recently published by Settlement House, will benefit a legal defense fund for the incarcerated youth, who are not constitutionally guaranteed legal representation under U.S. law.

“Poetry can prove a powerful tool for both introspection and interpersonal connection,” Michelson writes in the book’s forward, “and those twin possibilities seemed important to cultivate in relation to the presumed agonies of life in isolation cells in a foreign land.”

Out of necessity, some mystery surrounds this project. In exchange for permission to lead the workshops, Michelson — and his W&L students — agreed to the Department of Justice’s terms. They do not disclose the exact location of the facility, which is within easy driving distance of Lexington. They also do not discuss conditions at the detention center, the number of children incarcerated there, their countries of origin, or their names.

But most of these young people have a similar story. Most are from the most dangerous and violent places on earth. They were born into poverty, abandoned at a young age, and left to streets ruled by drug cartels. With no education or support systems, they set out for a better life — and they found America, but not long before U.S. Border Patrol or Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents found them.

The vast majority of undocumented and unaccompanied children who are swept up by immigration control forces do not end up in maximum-security detention; most go to group homes to wait out the determination of their residency status. Those who are sent to these “secure care facilities” have been assessed as a threat to themselves (i.e. self-harm or suicide) or others, based on prior behavior.

Although Michelson acknowledges the seriousness of the circumstances that put them there, he said, “these kids are languishing.”

“They are just like any teen, but when they do something wrong the consequences are catastrophic. They are mono-linguistic, many with no more than a 2nd-grade education. Many have been sexually traumatized. Many have a history of violence against themselves or others. Some have gang affiliations through no fault of their own, because the cartels are so powerful in their home countries. They are babies. Many are diminutive and pre-pubescent, and they are being locked up.”

For Michelson’s 10-week course, students spent Mondays and Wednesdays studying theories of belonging, current events, and immigration. They read poetry by prisoners and Latino immigrants. On Fridays, they traveled to the detention center and did poetry workshops, with each of the nine W&L students working one-on-one, one at a time, with incarcerated teens in each pod of federal detainees.

“Being from Tucson, Arizona, I thought I knew issues around immigration,” said Erin Ferber ’18, “but meeting with these kids, I was like, wow, there is a huge system that I didn’t even know about.”

Before the class began, people asked Ferber if she was afraid to enter the facility and visit so-called violent teens. She realized her only fear was that the kids, many of whom are younger than her 15-year-old sister, wouldn’t like her enough to open up to her.

Indeed, the class became as much about making connections as it was about Spanish or poetry. The W&L students used small talk to build relationships with the teens, bit by bit, before drawing them into larger conversational themes such as family, the journey north and dreams for the future. Some of these conversations eventually turned into poems.

Ferber describes the course as one of the most rewarding experiences she’s had at W&L, but she admits it was hard — not academically, but emotionally.

Once, after wishing a boy a happy 18th birthday, she wondered why he wasn’t more enthusiastic. Then she found out that he would be shipped to a men’s maximum security detention center because he was now considered an adult. Then, there was the kid who carved “I want to die” into his arm, and the teen who found out his entire family had been murdered back home.

Michelson knows the detention center can be traumatic, even for those who get to walk out and go home to free lives at the end of the class period. University psychiatrist Kirk Luder visited the class at the beginning of the term to discuss the effects of working with traumatized children. Michelson built in plenty of time for debriefing in class and in his office, and reminded students to take advantage of the University Counseling Center if necessary.

“He was incredibly supportive and passionate about it, which I think really cultivated this environment of inclusivity,” Ferber said. “He made sure we were comfortable and, in turn, could create these spaces where the kids felt comfortable enough to talk to us.”

Michelson said he experienced “unanimous, unflagging support” from his colleagues, Dean Suzanne Keen, Provost Marc Conner and the Office of General Counsel throughout the process. He said that being able to do a class like Poetry and the Politics of Immigration at W&L makes him feel fortunate to be part of the university community.

One thing that does bother Michelson and his students is the fact that, because of the DOJ restrictions, they had to publish the works in “Dreaming America” without using the writers’ names.

“They have left behind family and friends to traverse countries via perilous pathways,” he writes in the introduction, “only to find themselves locked in cubicles of concrete and steel in the Land of the Free, where I am acutely aware of the painful irony in my obligation to publish their writing anonymously.”

Michelson continues to volunteer at the facility, and will teach the Latin American and Caribbean Studies capstone course there this winter. Next fall, he will teach another class at the center, a variation on the Fall 2016 course called Poetry in Prison: Immigration, Empathy, and Community Engagement.

“By learning with and from the incarcerated children in concert with focused coursework, each W&L undergraduate inevitably gains more refined, informed and nuanced insights into the relationships between theory and practice,” Michelson said, “thereby equipping her to grow intellectually and emotionally, and empowering her to add her voice more confidently and intelligently to the many democratic communities to which she belongs.”

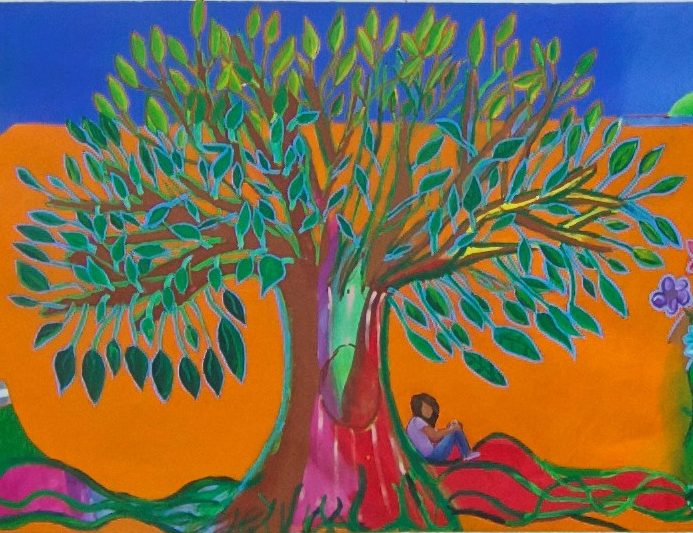

The mural below, “Tree of Life,” was made by undocumented children. It hangs in the maximum-security detention facility where Professor Michelson and his students did poetry workshops with teens. Click play to see all the details.

If you know any W&L faculty who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

More about "Dreaming America"

Seth Michelson will present an author talk on “Dreaming America: Voices of Undocumented Youth in Maximum Security Detention” on Nov. 7. The talk will take place from 5-6 p.m. in the Main Floor Book Nook at Leyburn Library.

The following poems are excerpted from the book.

Forget

Without reason to exist

I often forget that I am

real and this makes ache

the soul that I don’t have

or that can’t find me

as I wander

somewhere else.

— Anonymous

Hate

You enter, are

here speaking with me,

while others keep vigil

over their parents’ deaths,

while you and I are talking

others are at war,

others are killing boys and girls,

others are crying, others laugh,

others suffer,

others dance, and still others shout,

and I mull

my life’s frustrations.

If they wanted to write

what I know to be

happening, there wouldn’t be

ink

or paper enough

to write

everything that could be seen.

— Anonymous

To order a copy of “Dreaming America,” which includes a preface by poet and writer Jimmy Santiago Baca, click here.

This is a detail from a mural, “Tree of Life,” that hangs in the detention facility. To see the entire mural, scroll down.

This is a detail from a mural, “Tree of Life,” that hangs in the detention facility. To see the entire mural, scroll down. Professor Seth Michelson

Professor Seth Michelson “Dreaming America”

“Dreaming America”

You must be logged in to post a comment.