Eastern Art Meets Western Virginia Dr. Ling-ting Chiu, a Fulbright Scholar and assistant professor of history at Soochow University in Taiwan, spent the summer at Washington and Lee studying the works of former W&L professor and artist Professor I-Hsiung Ju.

Those familiar with the history of art at Washington and Lee will have heard of Professor I-Hsiung Ju, an artist-in-residence and professor at W&L from 1969 to 1989. Professor Ju’s name can be found on art still hanging on university walls, as well as on an endowment for art studies and on the Ring-Tum Phi’s 1971 award for Professor of the Year.

But Dr. Ling-ting Chiu only recently became acquainted with Ju’s work. A Fulbright Scholar and assistant professor of history at Soochow University in Taiwan, Chiu came to Lexington in June 2018 to study Ju’s life, legacy and art. She has taught courses in both Chinese and Taiwanese art history, and has published four books in those areas. Her next book, she hopes, will be about Professor Ju.

Chiu’s current research studies the impact of traditional Chinese artists, specifically Chinese literati painters, who went overseas to practice their art. Born in Jiangyin, Jiangsu, China in 1923, Ju came to the United States in 1968 and became an artist-in-residence at W&L the following year. Among his many art classes, he taught literati painting.

“He was a very versatile artist,” Chiu said.

Literati paintings are done in black ink and bold yet delicate brushstrokes, often focusing on beautiful landscapes and the expressions of nature. More than the beauty of painting itself, Chiu says, literati is about the artist behind the canvas: “The research of literati painting is not about the style of work, but about the challenges the painter faced.” She believes that studying Ju and his work in Lexington will provide a new perspective of literati painting untold in current academia.

Chiu first learned of Ju from his daughter, Jane Ju, an associate professor of art history at National Chengchi University in Taiwan. “The academic trend has been to really focus on literati painting in one place: Taiwan or China,” Chiu said. “We were ignoring overseas painters like I-Hsiung Ju, but it’s important to recognize the role they play in the tradition.”

Since arriving in Lexington for on-site research as a Fulbright Visiting Scholar, Chiu has been working closely with staff throughout the university. Leyburn Library, Special Collections and the Global Learning Center have all contributed to helping her document the impact that Ju had on campus as both an artist and educator. The Reeves Center has played the special role of introducing her to many of Ju’s paintings still in University Collections of Art and History.

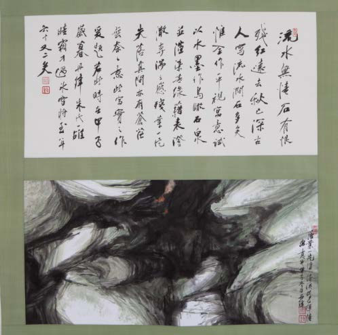

Chiu’s favorite piece is “One Autumn Leaf,” which portrays a “relentless flow of water,” “stones full of hate,” and a falling red leaf, seen as if looking from above. But, she explains, the true expertise of this painting isn’t in its style or skill — or even the poetic phrases that grace the top of the painting — so much as the feeling it is meant to portray to the viewer.

“For a realist painter, water, stone and leaves are just objective existences, but for a literati painter, each existence shares the mood of a moment from the painter,” Chiu said. She noted that Ju was 62 when he painted “One Autumn Leaf,” and that the water and stones in the painting are symbolic of his feeling of life.

While the format of the painting has many elements of traditional literati painting, the bird’s-eye composition, a break with tradition, highlights Ju’s mastery for combining the traditional and the modern. Chiu’s research is focused on this shift: how overseas literati painters took traditional styles and techniques and used them in new ways, bringing Eastern art to the West.

But Chiu wanted to explore Ju’s influence as both an artist and educator at W&L, so she interviewed many of his former students. That included those who attended W&L and took his classes, and those who studied under him at the Art Farm, which he and his wife, Chow-Soon, opened in Lexington after he retired from W&L. These interviews revealed the most interesting aspect of Ju’s work in America.

“I’ve spent a lot of time studying literati in Taiwan,” Chiu said, “but at W&L, my interviews are different. These students are now 60 or 70 years old, but when they talk about Professor Ju, they get teared-up. They were so inspired because his teaching wasn’t just about skill or painting, but about life and philosophy. When the students entered university, they thought he was just teaching literati painting, but when a literati painter paints, he shares a piece of himself. So when they were taught, it wasn’t just how to paint; it was about the life and the personality of the teacher. And they still carry that with them.”

In Chiu’s eyes, this revelation makes Ju an important figure in the “East-to-West” transfer of art, and provides a new perspective in rethinking the value of literati in the 20th century.

“I am fully aware of the love and influence that Professor Ju left behind,” said Chiu, who will finish her research in August. “Ju’s case shows us how a Chinese literati painter had a great influence on these American students in their early lives.”

Dr. Chiu stands with one of Professor Ju’s paintings.

Dr. Chiu stands with one of Professor Ju’s paintings. “One Autumn Leaf” by I-Hsiung Ju

“One Autumn Leaf” by I-Hsiung Ju

You must be logged in to post a comment.