Ancient Tablet is ‘Exquisite in its Simplicity’ In the first installment of this new series, Tom Camden offers the story of a Sumerian clay tablet that is the oldest recorded document in W&L's Special Collections.

Editor’s Note:

Welcome to “Out of the Vault,” a brand new series in The Columns that will highlight the many fascinating objects in Special Collections at Leyburn Library. Through the ages, Washington and Lee University has been a trusted steward of important documents; today, it is home to many rare books, manuscripts and other intriguing finds.

Some of these items are on display for the campus community and visitors to see, while others are currently housed in the vault. In addition, the university frequently acquires new objects for Special Collections. In monthly installments written by Special Collections staff, “Out of the Vault” will tell the stories of some of these items, from the oldest objects to the most exciting new acquisitions.

If this subject matter is of interest to you, you may enjoy our other new series, “From the Collections,” about items in the University Collections of Art and History. New installments in these series will appear monthly in The Columns.

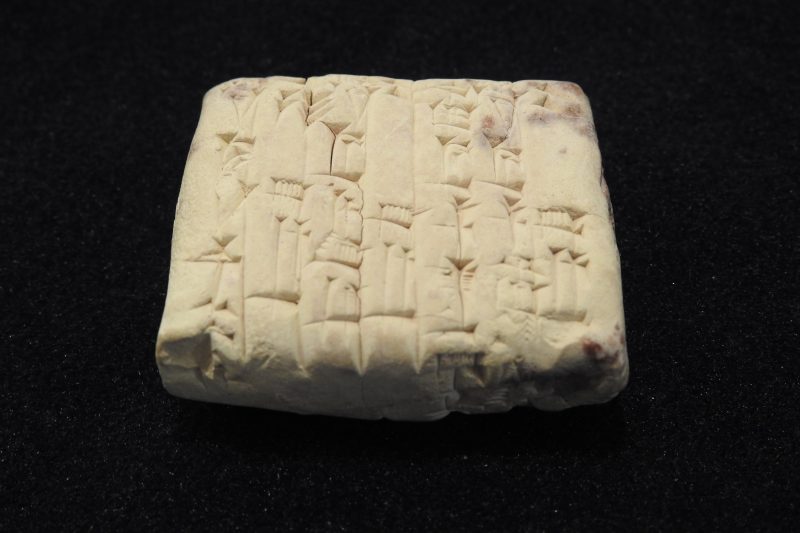

Quite plain, yet exquisite in its simplicity, the tiny clay object lies nestled in its recently crafted, elegant custom-made protective enclosure.

This Sumerian clay tablet is one of Washington and Lee University’s most intriguing treasures, and the oldest recorded document in the collection. It dates from 2030 BCE and resides in the vault in Leyburn Library’s Special Collections, where it has been housed since it was given to W&L in 1983 by Jean Knight of Buena Vista. Her husband, Benjamin P. Knight Jr., was a 1929 graduate of the university.

The little clay tablet, which measures 1 ½ inch by 1 3/4 inch, is from the southern Mesopotamian (Iraq) city of Ur (Ur of the Chaldees). Written in Sumerian, it is just over 4,000 years old. The form of writing is known as cuneiform (wedge-shaped), and was, at the time, the only type of writing that was known. Cuneiform was invented in the same area because of the prevalence of clay and reeds, which were used to make the tablet and stylus and form the characters.

The tablet itself is a commercial document and relates to the distribution of wheat to certain individuals. Because it references specific rulers of Ur, we are able to determine its date of origin. From the Sumerian King Lists, it is known who ruled Ur during this last century of the Third Millennium BCE, and two of the five kings of this Ur dynasty are actually mentioned in Washington and Lee’s tablet. The kings who had their capital at Ur, which is well known to biblical scholars as the home of Abraham, had a uniform method of keeping the record, as is evidenced by the tablet. Abraham himself would have been familiar with the wedge-shaped cuneiform writing in which all business and official correspondence was then conducted.

While Washington and Lee’s tablet records the distribution of wheat, many similar tablets recorded the tax on grain and other products, or provided instructions to priests or temple servants. Others were contracts, lists of sacrifices, or records of the payment of salaries from temple stipends. Still others were inventories of sheep and goats, and some were records of payments made to messengers who traveled from city to city.

Sumerian tablets are molded from clay that contains a great deal of marl or chalk and was relatively free from grit. After the cuneiform characters were marked in the damp clay by a scribe, the tablet was then sun-baked or kiln-dried. These tablets would have to be periodically re-fired, or baked even harder, in order to be preserved.

This lends another intriguing and powerful aspect to W&L’s tablet, which was recovered from ancient ruins. About 24 years after the tablet was created, the Sumerian government experienced a rapid collapse, possibly brought on by famine. In 2006 BCE, southern Mesopotamia was invaded by the Elamites from southern Iran, who attacked Ur, took the last king captive and burned the city of Ur to the ground. One side of W&L’s tablet shows the very distinctive scorch marks of that burning.

The Sumerians disappeared forever. However, the tiny clay tablet that remains is a poignant reminder that the fires of destruction that destroyed Ur likely ensured the preservation of Washington and Lee’s oldest document.

Click here to watch a video about this tablet.

At more than 4,000 years old, this Sumerian tablet is the oldest object in W&L’s Special Collections.

At more than 4,000 years old, this Sumerian tablet is the oldest object in W&L’s Special Collections.

You must be logged in to post a comment.