Get in on the Spring Term Action! We asked professors to share course materials and discussion questions to offer a sneak peek at the breadth of opportunities available during the best term of the year.

Alumni wax nostalgic about their Spring Term opportunities, parents and staff eye the course list longingly, and prospective students? Well, they can only imagine the fun, fascinating educational experiences that await them if they matriculate at Washington and Lee.

For anyone who is not fortunate enough to be enrolled in one of W&L’s many exciting Spring Term classes, we offer an alternative: The chance to dip a toe in one of several courses by checking out some of the material featured in the lesson plans. We asked professors to share some of those materials, along with discussion questions and a few thoughts on their courses.

After reading an article or excerpt, viewing a documentary, movie or television show, or listening to some sweet jazz tunes, feel free to ponder these questions. You could even turn it into a learning party and invite family or friends to a “Spring Term club” meeting!

The best part of our Spring Term read-along/view-along? There will be no pop quizzes, no final exams and no grades—just a chance to join in the thrill of learning.

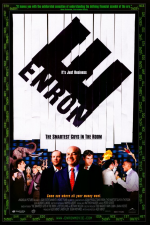

Course: Anatomy of a Fraud

Taught by: Megan Hess, assistant professor of accounting

Watch: “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room,” a documentary that is available for rent through Amazon or your local library.

NOTE: This documentary is rated R for nudity and profanity.

Hess says: “My two goals for this class are to empower students to be able to detect fraud and, more importantly, to prevent it in the first place. I believe that the best way to do those two things is to understand why fraud happens. The Enron case study helps us understand the underlying psychology…There were thousands of people at Enron who knew things were not right, but there was only one person who spoke up about it. If you really want to understand how fraud happens, you have to understand group psychology and how good people start down a slippery slope by rationalizing bad behavior.”

Discuss:

1. How would you describe Enron’s culture – that is, the view employees shared about how business works, the values they held to be most important, and the qualities they admired? In what ways did this culture help to make Enron both the most admired company in America and one of its biggest frauds?

2. What role did Enron’s formal systems, especially its performance evaluation plan, play in this fraud?

3. Who were the “watchdogs” that were supposed to keep Enron in check? In what ways were they complicit in its failure, and why do you think they failed to uphold their duty to protect the public interest?

4. Why were so many employees afraid to speak up about the problems at Enron? What made Sherron Watkins different?

Bonus assignment: Check out a new documentary series, “Dirty Money,” which is currently available on Netflix, to learn about more recent cases of fraud. Dr. Hess recommends the episodes about Volkswagen and Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

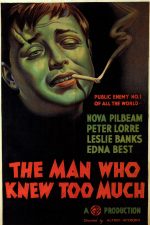

Course: Topics in American Literature: Alfred Hitchcock

Taught by: Edward Adams, professor of English

Watch: “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934 British version starring Peter Lorre) and “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956 American version starring Jimmy Stewart and Doris Day)

Discuss:

1. Hitchcock directed the 1934 version before he knew he’d be drawn to America by the producer David O. Selznick, who brought over England’s leading director after the huge success of “Gone with the Wind” in an effort to continue his run of spectacular financial and critical successes—with “Rebecca” as the Oscar-winning result. “The Man Who Knew Too Much” was one of series of films made by Hitchcock with the rise of Nazi Germany in mind. The later version is one of a series of 1950s films made by Hitchcock long after he’d decided to stay in America—and even become an American citizen—that similarly address the Cold War. Which film do you find more interesting as a “Cold War” or “war threat” film? How would you compare the British patriotism at the center of the first film to the American patriotism in the second one? What do you think of the strong sense that the later film also develops the notion of the so-called “Ugly American,” that is, the American abroad who demonstrates an easy sense of superiority, even disdain, for foreign customs and values?

2. One of the oddities of Hitchcock’s critical and cultural status as a leading director—perhaps the greatest director of the 20th century—is that he didn’t make epic films. Ambitious epic films with high production values, long running times and heroic themes of national greatness (or sometimes failure) are almost required for a director to be placed in the highest rank, yet Hitchcock shied away from them. “North by Northwest” is Hitchcock’s closest approach to an epic film, though the 1956 “Man Who Knew Too Much” has some claim to that status. What epic qualities do you find in this film? What ultimately disqualifies it from being an epic, if indeed you reject giving it that generic status?

3. Hitchcock was eloquent and precise in describing how the most effective suspense in a film depended upon the viewer being carefully instructed in what exactly is happening, the precise logic of the task the characters must perform, and how the characters themselves understand their task and its demands as well. (In short, Hitchcock disdained suspense in the form of a confusing mish-mash of action, no matter how spectacular and fast-paced.) How does the remake of this film demonstrate his careful attention to explaining the logic of the film’s action in order to create the maximum suspense?

4. The 1956 version is the only example of Hitchcock remaking one of his earlier films. To be sure, other later films often redo or update earlier films in less explicit ways—for example, the 1950s “North by Northwest” clearly reworks, refines, and expands central features of his 1939 film “The 39 Steps”—but “North by Northwest” is not a full-blown remake. Why do you think he chose to remake only this film out of all his early films?

Course: Seminar in Literary Studies: Neo-Slave Narratives

Taught by: Ricardo Wilson, assistant professor of English

Watch: “Django Unchained” (2012) and “Birth of a Nation” (2016)

NOTE: “Django Unchained” is rated R for strong graphic violence throughout, a vicious fight, language and some nudity. “The Birth of a Nation” is Rated R for disturbing violent content, and some brief nudity.

Wilson says: “My class, at its heart, asks two questions: How does an engagement with the genre of neo-slave narratives help to develop our thought about the institution of slavery across the Americas? And, perhaps most importantly, how does this body of work force us to reexamine our cultural inheritance? These questions are particularly urgent at an institution that is now attempting to situate itself in relationship to its own slave history.”

Discuss:

Both Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” (2012) and Nate Parker’s “Birth of a Nation” (2016) address, in quite different ways, ideas of rebellion. What do the respective visions do to productively unsettle or problematically reify our understanding of what we inherit?

Course: A Year in Jazz: 1948

Taught by: Terry Vosbein, professor of music

Listen to: “Elegy for Alto” and “Machito,” both performed by Stan Kenton

Read: “What’s Wrong With Kenton?” an article available on this webpage

Vosbein says: “The music industry was undergoing significant shifts in 1948. Stan Kenton became the first jazz leader to gross a million dollars at the box office, all while playing experimental Progressive Jazz. Bebop had virtually replaced swing for young musicians. And the American Federation of Musicians called a year-long strike against the recording industry, in an effort to protect the livelihood of musicians. It was a tumultuous year for the music industry, pitting creative artists against the machinery of the record and radio industries. Students will gain insights into the history of the music industry, and learn of the parallels facing contemporary music industry issues, and how it affects their consumption of music today.”

Discuss:

1. In listening to the two tracks, can you imagine how such experimental music, being sold under the name of jazz, became top box office in 1948?

2. Imagine yourself a Big Band fan during the era. Review tracks by Glenn Miller, Count Basie or Tommy Dorsey to understand the sounds generally associated with Big Band jazz. What sort of reaction might you have in hearing Kenton’s music in a concert setting, far from the dance floor from which it evolved?

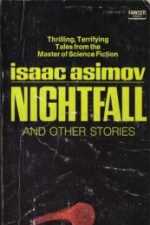

Course: Philosophy and Science Fiction

Taught by: Nathaniel Goldberg, professor of philosophy

Read: Isaac Asimov’s short story, “Nightfall” and Plato’s dialog, The Republic, Book One

Goldberg says: “Philosophers play with concepts. When Socrates kick-started Western philosophy, he struck up conversations. Some still engage in ‘public philosophy,’ as Chris Gavaler (my colleague in English) and I do in our forthcoming book, ‘Superhero Thought Experiments.’ But the best ‘public philosophy’ is done by science-fiction writers. Science fiction allows writers to play with concepts such as knowledge, justice, and reality. My class investigates what can be learned by reading academic and public philosophy together.”

Discuss:

1. In “Nightfall,” in what way is knowledge on Lagash cyclical?

2. Is knowledge on Earth cyclical?

3. Does “Nightfall” suggest anything about, or do you have any thoughts on, what political system might be best at breaking the cycle?

4. In Book One of The Republic, what are Cephalus’s and Polemarchus’s concepts of justice, and what do you think of them?

5. How does Thrasymachus challenge the very idea of doing philosophy?

6. Is there a concept of justice that might be best at helping society break the cyclical nature of Lagash’s, or our, knowledge?

Course: “Black Mirror”

Taught by: Stu Gray, assistant professor of politics

Watch: Season 3, Episode 1: “Nosedive” and Season 3, Episode 4, “San Junipero”

Read: “Engaging Transhumanism,” an article by Hava Tirosh-Samuelson (chapter one of this document)

NOTE: “Black Mirror” episodes include mature themes that some viewers may find disturbing.

Gray says: “The television series ‘Black Mirror’ asks us to reflect on some of the very deepest personal, ethical and social-political issues that face contemporary and future societies, particularly issues surrounding various forms of gadgetry and technological ‘development.’ In an age of increasing technological acceleration, the show’s dystopic visions dare us to question what it means to be human, the nature of reality, and what qualifies as a desirable social-political relationship. In doing so, the show presses us to use our imagination to conceive of worlds that we may or may not want to inhabit—it should both haunt and inspire us.”

1. What are the major lessons, or take-away points, from “Nosedive”? Why might future human societies want to develop this sort of technology and associated practices? After all, aren’t we already engaging in these types of social assessments and evaluations? What’s wrong with ratings? Consider the various types of social media and those that may develop from existing forms. Would such rating systems make us more kind, respectful and responsible to one another…or would they be more likely to induce the psychological states we see exhibited at the end of the episode?

2. If you were to be born and live in the sort of society depicted in “Nosedive,” what would you do?

3. Tirosh-Samuelson: What struck you most about this chapter? According to Tirosh-Samuelson, what is transhumanism’s conception of human nature, the good life and happiness (29-33; 35-39)? As a bridge to our discussion of “San Junipero,” what is Tirosh-Samuelson’s assessment of radical life extension (39-42)? Do you agree with Tirosh-Samuelson that aging is not such a dangerous thing to be avoided? Why?

4. What were your initial reactions and thoughts regarding the episode “San Junipero,” its major characters and themes, and its plot twist? What lessons might we take from this episode?

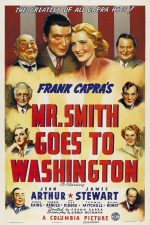

Course: Seminar in Politics, Literature and the Arts (Bill approved)

Taught by: Bill Connelly, John K. Boardman Jr. Professor of Politics (After three decades of directing our spring Washington Term Program in D.C. Prof. Connelly is teaching his first ever spring term course on campus.)

Watch: “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” (streaming or available at local libraries)

From the professor: “I argue in the course that the Jimmy Stewart character embodies the perspective of the Anti-Federalists, i.e. the critics of the Constitution. The movie correctly identifies the defects of Congress, many evident today; yet, the ‘cure’ remains elusive at best. James Madison, in the Federalist Papers, offers a more realistic perspective on Congress.”

Discuss:

- What is the argument of the movie?

- What ideal does the Jimmy Stewart character, Jefferson Smith, represent?

- Does the Jimmy Stewart character embody the Federalist or Anti-Federalist perspective?

- What is the essential criticism of Congress and the American political process articulated in the movie? Is the criticism accurate?

- What defects of Congress does the movie identify?

- What cures to the defects of Congress does the movie offer?

- Who saves Jefferson Smith from defeat and despair — and how?

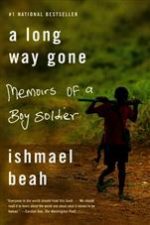

Course: Special Topics in Literature in Translation: The African Child Soldier

Taught by: Mohamed Kamara, associate professor of Romance Languages

Read: The novel “A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier” by Ishmael Beah

Kamara says: “To be honest, this is a course I would rather not teach. However, the militarization of children and everything that comes with it are a part of our reality. We cannot shy away from this reality if we are to become a more perfect species. After all, how can we expect to make better decisions as individuals and citizens of the world if we are not ready to face and learn from our mistakes? It is natural for a story about the militarization of children, especially when told by the children themselves, to be heartrending. Yet, in the middle of all the gore and gloom, students will recognize and celebrate the human spirit and all that is admirable about it: courage, resilience, adaptability, kindness and love.”

Discuss:

- Reflect on the various ways Ishmael portrays the disappearance of his and other children’s childhood. What effects does the seminal transformation have on them and society?

- To what extent do rap music and other elements of Western culture influence the attitudes and actions of Ishmael and others? What does this tell us about the universality and universalization of culture? Think more specifically about the role of literature (Shakespeare) and film (Rambo).

- Can one be a child and a soldier at the same time? How do Ishmael and other child soldiers grapple with the notion of childhood and the confusion that accompanies the treatment and participation of children in armed conflicts? What does the oxymoron say about society in general?

- What factors make the oxymoron of the child-soldier possible in the first place? In other words, how and why do Ishmael and his friends become (and, in some cases, want to stay) soldiers? In answering this question, reflect mainly on the role played by (1) family in all its forms, in its presence or absence, and (2) the allure of the power to be somebody and to access material necessities of life.

- Are Ishmael and other child soldiers responsible for their actions? To what extent should we hold children criminally culpable–if we should–for their ‘crimes’ committed under adult supervision, regardless of whether they cease fighting as children or adults?

- How do the actions of Ishmael and his friends illustrate their capacity for adaptability and resilience during and after their engagement in fighting?

- Prevention, to be sure, is better than cure. What role can we as parents and guardians, adult brothers and sisters, and citizens of the world play in the prevention or mitigation of the militarization of children?

Click here to read more about W&L Spring Term courses.

Ricardo Wilson, assistant professor of English, with his Spring Term class, Seminar in Literary Studies: Neo-Slave Narratives

Ricardo Wilson, assistant professor of English, with his Spring Term class, Seminar in Literary Studies: Neo-Slave Narratives

Stu Gray, assistant professor of politics, talks with students in his class, “Black Mirror.”

Stu Gray, assistant professor of politics, talks with students in his class, “Black Mirror.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.