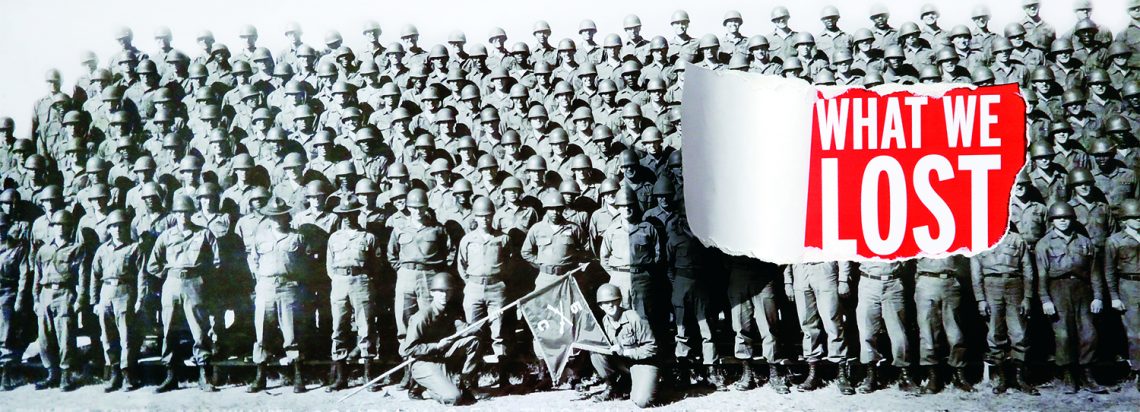

‘I Have Been a Very Lucky Man’ John Gulick '63, who served as a Navy SEAL in Vietnam, was on the wrong end of an ambush about one week after his arrival in country.

“Looking straight ahead at our direction of travel, I saw a huge water spout rise up before me … I didn’t know what the source of this waterspout was, but it had to be serious. Every gun on the boat began firing … for our survival.”

— John Gulick ’63

John Gulick ’63 served in Vietnam as a lieutenant in the Navy SEALs. He was awarded a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart for his valor. Here, he tells the story of his first night mission in Vietnam, and how that experience affected him for the rest of his life. This essay was originally published in The Blast, the newsletter of the UDT-SEAL Association. It was written just before he returned to Vietnam for a 2001 visit. “I think I wrote it to free up some uncomfortable feelings about going back there,” he wrote in an author’s note. This essay is shared here with permission.

After about a week in country and getting acclimatized, it was time for my platoon to set its first night ambush. We were split in two fire teams consisting of six enlisted and one officer. I was the most junior SEAL officer in the whole place, but I thought my job was more like an E-5 (a second-class petty officer, or lower). We hod gone on a simulated patrol, just to get our feet on the ground. When we did this, I realized that I was in a war and had to face all the risks involved in such an endeavor. The thought come to mind: What is a guy fresh out of college from Somerville, New Jersey, doing here? Trouble was, I was no longer that naive boy, and I had spent the ensuing years, after leaving home, trying to become a tough guy who was willing to do anything — and the universe was now calling for me to really be that, instead of play-acting.

So we had a briefing of sorts, but I don’t remember much of anything about it. In typical fashion, we rode a modified Landing Craft, Medium, Mike boat. It was nicknamed “Mighty Moe,” and it was something. Someone had gun decked over the cargo hold, so that instead of being completely open, our boat had a heavy deck above the regular deck. There were .50 Cal. machine guns (two forward, two amidships and one in the stern). We also had two .30 Cal. machine guns next to the coxswain’s station. There was a small sand mortar pit, from which we could fire a 60 mm mortar, in the center of the deck, just forward of the coxswain’s station. Above the coxswain was a sand bagged platform where we had a recoilless rifle. We were definitely loaded for bear. On this particular night, my platoon was the cargo, and the boat was manned with all SEALs except for an engineman and a blackshoe LCDR running the show and a crewman who manned the rear .50 Cal. machine gun.

Dave Janke and half of our platoon were to disembark first, and I would go in with the rest. We shoved off from Nha Be around 6 p.m. and motored along for the Long Tau River. The Mike boat’s engine had a calming rumble, and the smell of diesel was comforting because it was so familiar a smell in a place where the smells were all new and foreign. As we rode along, I chatted with my good friend, Bill Pechacek, and he was telling me about how he was soon getting out of the Navy, and he thought he would go into the CIA — as he had been recruited. Funny, I remember Bill as my friend, yet the SEALs are so unique that every man there was my friend. No matter officer or enlisted — we lived together and were frogmen/commandos together. We shared everything, and so we were unique in military life, and we were all brothers and comrades, each one willing to give everything for the others.

The time came for Dave and his men to disembark, and I really don’t remember much about that. Such an evolution takes very little time, and when the men are off the boat, they quickly fade into the brush and are gone, completely swallowed up by the swamp vegetation. Then, we proceeded on to where my men and I would get off. We rode a short while, and I called for my men to assemble at the lead edge of the gundeck. We all just sat around watching the dusk take over and the colors becoming muted. It really was a very tranquil sight, and I don’t remember being apprehensive. I was just green.

Then, something happened. Looking straight ahead at our direction of travel, I saw a huge water spout rise up before me. I froze in time, and I thought back to the “Victory at Sea” series about WWII, where many waterspouts were depicted, coming from bombs from planes and shells fired from guns. I didn’t know what the source of this waterspout was, but it had to be serious. Every gun on the boat began firing, suppressing fire — for our survival. My team didn’t have anything to do. Our station was below the gundeck and standing by for orders. We would be anything, from a landing party to reserve gunners or ammo handlers, if someone went down. Sounds good, but I am a very impatient man, and standing around watching Tom Truxell serving as an ammo handler, and as cool as could be, didn’t help. I decided that I should go to a portion of the lower deck and climb the coxswain’s ladder to the gundeck and see if I could help, or be of more use.

I climbed the ladder and thrust my head and shoulders above the surface of the gundeck. When I did that, I heard incoming bullets up close and personal for the first time. What an interesting and menacing sound they make. It gets even better when they strike the metal side of the boat or objects that are metal. Gene Krupa would have been proud of those VC gunners for the music they made beating a tattoo on our boat. But for me, it just meant that this place was inhospitable in the extreme, and that my place was back down below with my men. With that, I began descending the ladder, on which I had been standing while I evaluated the situation and got my first dose of combat religion.

When I reached the bottom of the ladder, I turned and took a step. At that moment a mortar round went off above me and made the loudest sound I have ever heard. I felt like someone had used a bath towel rolled up to whip me in my left leg. The mortar’s blast came down the ladder, and had I been descending when it hit, instead of already down the ladder and a step away from it, I would have been struck by a lot more of the fragments and blast. The implications of that possibility have often occurred to me over the years. Who handled the timing of my descent? My leg stung, and the impact felt somewhat forceful, and I realized that I had been wounded. After checking my men, who were all okay, I went back up the ladder to see what had happened topside. When I got there, it was pretty dark and smoke was still blowing, from the mortar and the machine guns, which were now silent.

Men lay prostrate on the deck, and it looked very bad. My first impulse was to find out if any officers, besides me, were available to take the con, and as far as I could tell, there was no one but me. The problem was that if we continued deeper into the swamp, I didn’t know my way around and didn’t feel confident that I could get us home. So, I told the coxswain, a character and very significant badass, Leon Rauch, to turn the thing around and go back the way we had come. Leon had some kind of compress on his face and a blood streak running down it, and I thought he was such a magnificent pirate — and he was. But Leon didn’t like the order I gave him, and, well, he shouldn’t have. A basic tactical rule is never return to an ambush kill zone, and that is what we were in. More than that, we were dead in the water, as our diesel engine crapped out when the mortar hit. Our non-SEAL engineman went down into the engine space and performed some kind of magic, and we had power again. By that time, our senior officer surfaced, wounded and in pain from a collapsed lung from mortar fragments, and countermanded my order to Leon, and we proceeded away from the ambushers.

I then walked around to the stem of the boat to see the rear .50 Cal. gunner prostrate and out with his weapon unmanned. I could see muzzle flashes from the ambush position and decided that I would take them under fire. I hesitated before I began to fire, because that is the way to draw return fire, but I did it anyway. The .50 was damaged and wouldn’t fire on automatic. I had to chamber a round each time I fired, and that got old fast. I then came back to the coxswain’s station and noticed a lot of commotion around Bill Pechacek. He was down being attended by Joe Churchill, our chief corpsman, a veteran of WWII, the Chosin Reservoir in Korea and now Vietnam. Soon Joe instructed us to muscle Bill down to the bottom deck, out of the way of any other gunfire, and to a place where Joe could work on him. I grabbed Bill’s head and left arm as we man handled this big man like he was a sandbag. When we got him down, Joe looked at me with a lot of emotion and said, “I don’t think he is going to make it.” I don’t recall feeling a thing. It was then that I noticed something very thick and viscous on my hand and looked in the poor light to see what it was. Joe saw me do that and said, “That’s Bill’s brains.”

We then got the boat to a place where our seriously wounded could be medevaced out, and choppers came in and got that done. Those of us not wounded or not seriously wounded remained on the Mike boat to crew it back to Nha Be, and this included me. But I was getting seriously uncomfortable as the little slap on my leg got stiff and painful. We succeeded in getting the boat in, and a chopper was waiting for me. I got on for the ride to the 3rd Army Field Hospital, just near the airport in Saigon.

When I got to the hospital, I only remember waiting. Bill Pechacek was the worst of us and would need hours of neurosurgery, and I needed almost nothing — just basic debridement. I remember looking at Bill unconscious on his gurney and thinking that I couldn’t imagine anyone alive with such horrific wounds. His back was crisscrossed with cuts from the mortar, maybe 200 of them. His head was encircled with bandages, and he was out.

The doctor finally came for me, and I walked to a table where I took my pants off and laid on my stomach. I don’t remember pain — only unpleasant tugging and pulling on my leg. I don’t recall how long it took, but finally he told me that he was finished. I stood and looked down on the floor to see what looked like ground beef strewn around by a careless hamburger patty maker. I asked what that was, and the doc looked at me for a long moment and said, “that’s you.” With that cheerful bit of information, I limped after an orderly or nurse to my bed. The day was over, and maybe it was even the next day. And I was numb, but grateful that I wasn’t Bill about to go into many hours of surgery.

The next day, the Admiral, who was in command of all Naval forces in Vietnam, came to the hospital and handed out Purple Hearts to us. Leon’s bed was next to mine, and I don’t remember talking to him about the Admiral. But, I did think that it was nice that the Admiral pinned a Purple Heart Medal on my pajamas. Leon, being who he was, managed to get a mirror that he placed on a pair of slippers next to his bed. It was strategically positioned so that he could look down at the mirror when a nurse came to talk to him and see upward — hopefully at what was under her skirt. Suffice it to say that Leon had a mischievous and resourceful side to him.

Turned out that Bill Pechacek would never walk again without crutches and would be destined for months of coma, only to miraculously come out of it, completely disabled and unable to speak or read or anything so that his dad was made his guardian. Lesser men wouldn’t have lived or persevered the way Bill did to relearn everything. In time, he became a teacher, married, and had children. Unfortunately, injuries like his don’t get better, and he died early. But he made the most of what was left for him, and after all these years, his brains remain on my right hand. I can’t get it off; it has been with me every day that has been gifted to me as a reminder of how lucky I was that day.

Another aspect of the luck that has followed me everywhere is that we were ambushed from the very place that my fire team and I were supposed to be dropped off to set up our ambush. Had the enemy mortarman held his fire, we would likely have been hit as we disembarked into the water to wade ashore. This happened to other SEALs during the war, and some were killed doing it. Yet on October 7, 1966, the mortarman dropped a mortar into his tube and signaled us to return murderous fire. More importantly, my team and I didn’t get into that water that night. I don’t remember that we ever learned how many we killed that day, but it had to be a bunch — to allow for some speculation.

As the years have passed, I have no regrets or any guilt at all, and I didn’t when I visited Vietnam in January 2011.That visit included a trip into the Rung Sat from Nha Be, where I prayed for the souls of the dead, theirs and those of us who died early because of their injuries — mainly Bill Pechacek and Bob Henry. I also went to the mouth of the Varn Sat River, along with my friend and former UDT-12 teammate, Lance Mann, and to the site where my UDTRA classmates, Dan Mann and Ron Deal, were killed on April 7, 1967. We paused and said prayers for those men who died and those who were injured.

I have tried to live a good life, have loved my children and, despite many mistakes, I have done the very best I could. I didn’t earn the grace that was accorded to me, nor the gift of my own life. And I don’t take it for granted or take it lightly. I have been a very lucky man in so many ways.

If you know any W&L alumni who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

John Gulick (right) and his fire team accompany the head boat on a mission in Vietnam.

John Gulick (right) and his fire team accompany the head boat on a mission in Vietnam. The “Mighty Moe.”

The “Mighty Moe.” Action on shore.

Action on shore. The SEAL fire team back on board the Mighty Moe after a different operation.

The SEAL fire team back on board the Mighty Moe after a different operation. John Gulick ’63

John Gulick ’63

You must be logged in to post a comment.