Life in Disneyland A letter in W&L's Special Collections, written by former English professor George Harding Foster to Harrison Kinney '47, provides a glimpse of the inner workings at Disney Studios in the 1950s.

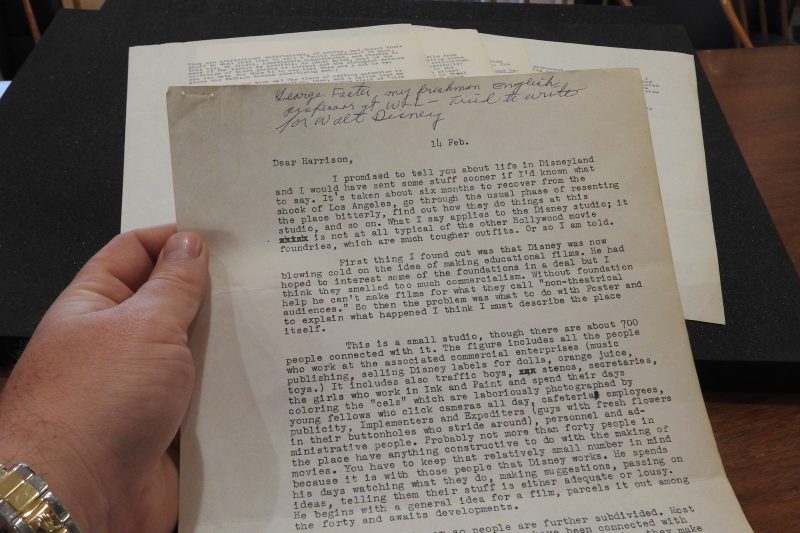

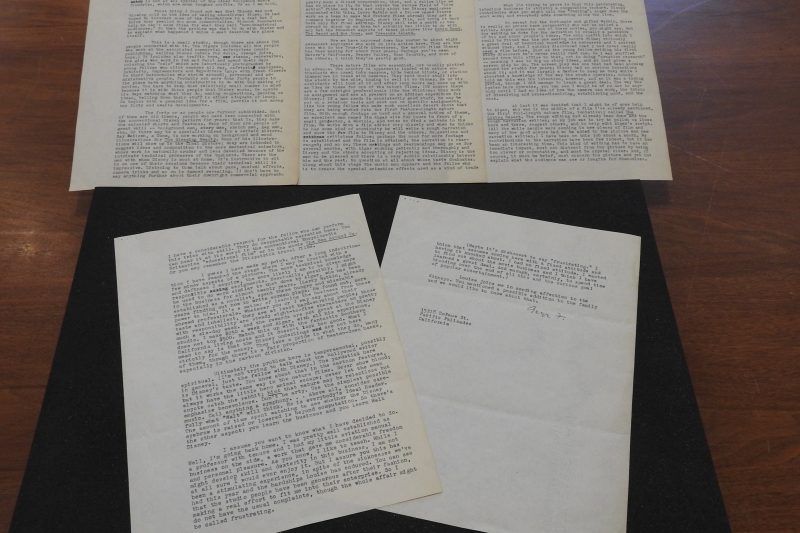

In early June, I received a research request by email that caught my eye immediately. The individual identified himself as a Disney historian, author and editor of a number of books about the Disney Studio and its artists. Unaware that we had any material in our archive related to Walt Disney and the Disney Studio but not completely surprised since our collection continues to yield heretofore unknown treasures on a regular basis, I searched our vault holdings for the single document requested. Once again, I was totally overwhelmed by the impact of a single five-page, typed letter.

George Harding Foster was on the English faculty at Washington and Lee in the 1940s before he left in 1952 to work for Disney Studios in Los Angeles. One of his students at W&L was Harrison B. Kinney ’47. Six months after commencing his tenure at Disney Studios, Foster wrote the most extraordinary letter to Harrison describing “life in Disneyland.” The letter, dated February 14, starts with Foster declaring “It’s taken about six months to recover from the shock of Los Angeles, go through the usual phase of resenting the place bitterly, find out how they do things at this studio, and so on…I would have sent some stuff sooner if I’d known what to say.” Foster goes on to describe the Disney operation in detail:

This is a small studio, though there are about 700 people connected with it. The figure includes all the people who work at the associated commercial enterprises (music, publishing, selling Disney labels for dolls, orange juice, toys). It includes traffic boys, stenos, secretaries, the girls who work in Ink and Paint and spend their days coloring the “cels” which are laboriously photographed by young fellows who click cameras all day, cafeteria employees, publicity, Implementers and Expediters (guys with fresh flowers in their buttonholes who stride around), personnel and administrative people. Probably not more than forty people in the place have anything constructive to do with the making of movies.

Foster goes into some detail about the work of the forty “specialists” he refers to as mostly “old timers” – background men, story men, sketch men, gag men, etc. or specialists who are hired for certain pictures, such as “Kay Neilsen, a Dane, now working on background and mood illustrations for ’The Sleeping Beauty.’” After much discussion of where he thinks he fits into the organization, Foster concludes by admitting:

…the rewards are not great at the Disney studio. I make $250 a week and Algar (a Senior Technician), with all his experience, does not top $500. Match this up with the fantastic Southern California living costs and it doesn’t look too good. What I mean to say is that the Disney underlings are not here strictly for the money. They take a pride in what they do, many of them, though there is a fair proportion of beaten-down hacks, especially in the cartoon division…ultimately, the problem here is temperamental, possibly spiritual. (I’m not trying to talk about the Hollywood writer in general, just the fellow with Disney). The yardstick here is Disney’s taste. You know about that in the cartoon features, but it works the same way in the nature films. Never show blood; always have the little hero animal escape; never let the mean coyote catch the rabbit; hint that nature may be relentless but emphasize benevolence. Don’t be arty. Use the simplest possible music. Call anything a symphony…Above all, consider carefully what “Walt” will think. He is everybody’s Ideal Reader. The amount of time spent watching to see whether the Disney eyebrow is raised or lowered is beyond computation.

Foster’s insightful letter to Harrison Kinney ends on a very pragmatic and somewhat surprising note:

I assume you want to know what I have decided to do. Well, I’m going back home. I was pretty well established as a professor with tenure…as you know, I like to teach. While I might develop skill and dexterity in this business, I am not at all sure I would ever enjoy it. But I assure you this has been a stimulating experience.

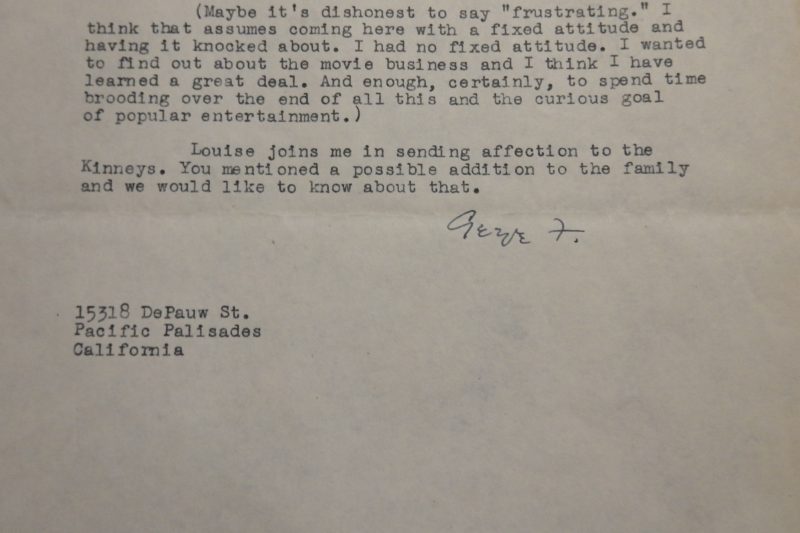

While Foster admits to his former student that working in the Disney Studio has been a “stimulating experience” and he does not harbor the usual complaints, he confesses that “the whole affair might be called frustrating.” He concludes, in a brief parenthetical statement, with a further explanation that speaks volumes about the early years of the Disney studio.

Maybe it’s dishonest to say “frustrating.” I think that assumes coming here with a fixed attitude and having it knocked about. I had no fixed attitude. I wanted to find out about the movie business and I think I have learned a great deal. And enough, certainly, to spend time brooding over the end of all this and the curious goal of popular entertainment.

Dr. George Harding Foster, W&L Class of 1934, returned to Washington and Lee University in 1953 as an associate professor of English after his one- year leave of absence at the Disney Studios. At his untimely death on Thanksgiving Day, 1959, he was serving as head of the Department of Comparative Literature. His remarkable letter regarding life in Disneyland is, to our knowledge, the only document we have in university archives related to his brief career in the movie industry. It is worth noting Harrison Kinney’s keen sense of posterity in saving this letter and presenting it to his alma mater. Harrison B. Kinney ’47 passed away on February 9, 2019.

A letter in W&L’s Special Collections, written by former English professor George Harding Foster to Harrison Kinney ’47, provides a glimpse of the inner workings at Disney Studios in the 1950s.

A letter in W&L’s Special Collections, written by former English professor George Harding Foster to Harrison Kinney ’47, provides a glimpse of the inner workings at Disney Studios in the 1950s. George Foster

George Foster .

. .

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.