Locating the Law In his most recent book, Russell Miller charts the constitutional history of Germany though text and images.

Mounted behind the judges’ bench in the German Federal Constitutional Court is a six-hundred-pound, hand-carved wood sculpture of an eagle. The Bundesadler, or Federal Eagle, is the symbol of the Federal Republic of Germany. Normally rendered in a sharp, precise—even aggressive—style, the sculpture by Hans Kindermann has a soft and living quality. The wings are not outstretched, but rather positioned as if to enfold the chamber and its occupants.

For Washington and Lee law professor Russell Miller, who has devoted his academic career to studying German law and legal culture, the Bundesadler in Karlsruhe has layers of significance. The wood in the sculpture comes from the Pacific Northwest where Miller grew up, and the sculpture itself hangs in the court where Miller was granted an unlikely fellowship 25 years ago that has since defined his scholarship and teaching.

“So here I am in that courtroom, far from home, far from my natural cultural identity and location, learning so much, learning to love that court,” said Miller. “And there’s this little connection to home through this really meaningful work of art in the courtroom. I resolved that if I could tell a story through that image about constitutionalism, I would try to do it.”

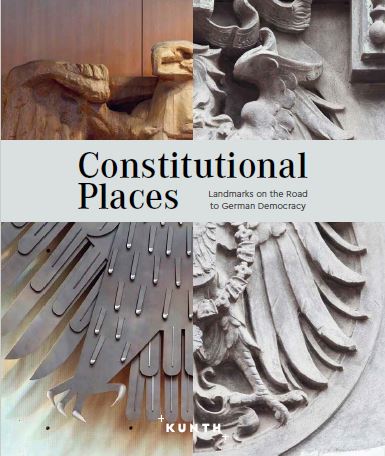

Kindermann’s sculpture can be seen as the touchstone for two major works of scholarship Miller has completed in the last year. The most recent, titled “Constitutional Places: Landmarks on the Road to German Democracy,” is a book of photos and text that Germans would refer to as a Bildband. While there is no direct English translation, a coffee-table book comes the closest to capturing the work’s look and feel. In fact, the project fits in with the emerging scholarly movement examining the materiality of the law, the notion that infrastructure and physical space can have as much impact on how the law works as do the words of statutes and laws. For example, Miller noted that the size and shape of the standard wax tablets used to codify the Roman Civil Code worked to confine the expression of legal principles.

“Even in my purely narrative work, I write about law as it interacts with society and how some cultural artifacts might actually inform our understanding of the law,” said Miller. “So this book is a total surrender to that methodology and to say, ‘yes, you should think about the law in cultural or aesthetic terms and adopt those media to tell that story’.”

Miller and his coauthors, along with the stunning photography of Alexander Telesniuk, trace the roots of German constitutionalism through 26 historical sites, stretching back far earlier than the Basic Law established in 1949. For example, one chapter focuses on an 1882 decision by the Prussian Higher Administrative Court—the Kreuzberg Judgement—that put a limit on state power over property rights. The decision, viewed by many scholars as the “wellspring of the Rule of Law” according to Miller, was handed down in a structure destroyed in World War II. Ironically, the most prominent structure in this location in East Berlin today, where the Rule of Law was born, is the North Korean Embassy.

Among the most somber entries is an exploration of the relationship between the Buchenwald Manifesto, written in 1945 by inmates of the notorious concentration camp just days after their liberation, and the simple preamble to Germany’s new constitution.

“The echoes of that manifesto can be found in the preamble to the Grundgesetz, the Basic Law, ‘Conscious of their responsibility before God and man’,” said Miller. “In 1949, it was clear to everyone what that meant: never again.”

Miller’s other significant project, published in 2024, is a book titled “An Introduction to German Law and Legal Culture.” The book provides an accessible introduction to the foundations of German law as well as to the theory and doctrine of some of the most relevant fields of law: Private Law, Constitutional Law, Administrative Law, Criminal Law, Procedural Law, and European Law. While not a companion piece to the Bildband, Miller acknowledges the “strong methodological link between the two.”

It is perhaps not surprising that the first American to clerk for the Federal Constitutional Court would take on the ambitious task of surveying and summarizing an entire legal culture. But that outsider perspective helped Miller understand that you can’t really tell the story of German Constitutional Law without some competence in other areas. Beyond that, one of the main reasons he wrote the book was to be the definitive guide for anyone with a need to understand German law and the German legal mind.

“Let’s say you are Croatian judge at the European Court of Human Rights, for example, sitting with 16 other judges on a German case involving some Administrative Law Principle,” said Miller. “This book is the way in.”

For Miller, an English-language treatment of the German legal system is especially important given its influence on developing democracies around the world as most of the new democracies created after the end of the Cold War adopted key components of the German post-war constitutional model.

“The German constitutional system is hugely influential in a place like South Africa, where the South African Court regularly hires German law specialists as clerks so that they have ready access to someone with expertise in German legal systems,” said Miller. “Almost all criminal law in Latin America is heavily influenced by the German Criminal Code, and private law all over Asia is heavily influenced as well.”

In fact, the one democratic country with perhaps the least in common with Germany when it comes to the law is the United States. However, Miller argues that doesn’t mean America has nothing to learn from the German approach to constitutionalism.

“There’s a lot of constitutional failure in the German story, but if you experience 500 years of constitutional failure, you also have a lot of constitutional determination,” said Miller. “What does it look like when everything goes wrong with your constitution? Do you quit? How do you put it back together? In their history, Germans keep returning to this dream, this constitutional dream, the commitment to democracy. And maybe, suddenly, that would be an important lesson for Americans to learn.”

If you know a W&L faculty member who has done great, accolade-worthy things, tell us about them! Nominate them for an accolade.

- Available in German at Amazon.de (https://amzn.eu/d/0PK2o2o)

- Available in English upon request from Markus Lang (m.lang@dnb.de)

Professor Russell Miller

Professor Russell Miller

You must be logged in to post a comment.