Prelude to Reformation Four Martin Luther tracts housed in W&L's Special Collections were fully restored in time for the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation.

Four years ago, one of my freshmen work-study students dropped by my office to ask if he could look at the Martin Luther pieces housed in the Special Collections vault. He had found them listed in the library catalog.

Of course, I encouraged him to pull the items for viewing, with one caveat: He had to show them to me first, since I had not seen them and was not aware that Washington and Lee owned early Martin Luther items. What we discovered was nothing short of sensational.

Exactly 500 years ago, on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a German theology professor, composer, priest and monk, nailed his “Ninety-five Theses” to a church door at Wittenberg, Germany, effectively launching a period of history known today as the Protestant Reformation.

On that fateful day, Luther had written to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his “Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” which came to be known as the “Ninety-five Theses.” The Latin theses were printed in several locations in Germany in 1517.

A few months later, supporters of Luther translated the “Ninety-five Theses” from Latin into German. Within two weeks, copies of the “Theses” had spread throughout Germany; within two months, they had spread throughout Europe. Luther’s writings circulated widely, reaching France, England and Italy as early as 1519. Students thronged Wittenberg to hear Luther speak, and this early part of his career was one of his most creative and productive. He made effective use of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press to spread his views, switching from Latin to German to appeal to a broader audience. In fact, between 1500 and 1530, Luther’s works represented one-fifth of all materials printed in Germany.

At some point in the latter part of the 19th century, Washington and Lee was given four early Luther tracts by Dr. Samuel Rolfe Millar. Millar, a Virginia native, had been appointed United States Consul at Leipsic, Germany by President Cleveland in March 1886. From the handwritten inscription made by Millar, it is apparent that he acquired the tracts while in Leipsic. Millar was guest lecturer at Washington and Lee University during the 1891-92 academic year, so the gift may have been made during that period. Dr. Millar’s son, Samuel Rolfe Millar Jr., graduated from Washington and Lee in 1911.

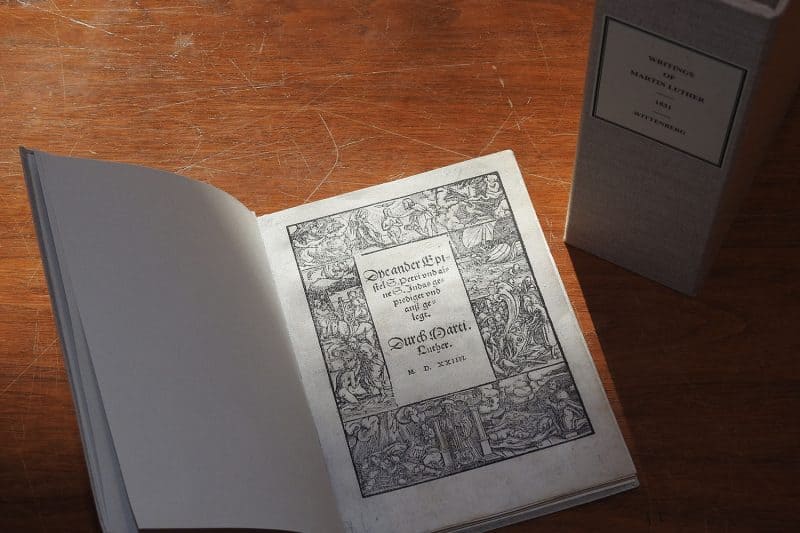

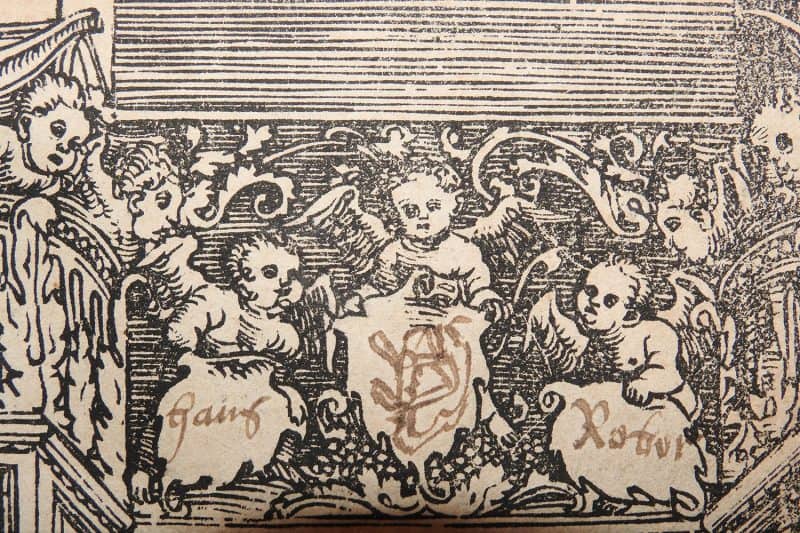

The earliest of Washington and Lee’s Luther tracts was done in 1523 and, like the other three, was printed in German. The title of the tract translates to “An Order of Worship for the Community,” and the tract is graced by an exquisite woodblock paper cover executed by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a staunch financial supporter and ally of Martin Luther.

The other three tracts, one published in 1524 and two in 1531, are sermons. The 1524 publication is a sermon on Peter and Jude, and the 1531 pieces include a sermon on Hebrews and one on angels. All have detailed woodblock covers, possibly done by Cranach, although the 1523 tract is the only documented Cranach woodcut.

After making such a sensational “rediscovery,” Special Collections has shared the Luther tracts in numerous classes and special group presentations. In fact, I was able to do some very detailed research on Luther’s writing during summer 2017. While in residence at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, I examined their Luther pieces for comparison purposes.

In light of the 500th anniversary of Luther’s “Theses,” and taking into account the increased attention to such wonderful rarities, the decision was made in winter 2016 to have full conservation work done on all four pieces. That conservation work, including full treatment of every leaf in each tract and the fabrication of elegant linen protective enclosures, was completed in late spring 2017.

In a fitting tribute to the impact of Luther’s simple paper tracts, the full restoration of the pieces was generously paid for by Joshua Duemler ’17. It was Josh, my dedicated and inquisitive work-study student, who brought these pieces to my attention nearly four years ago.

Who knew that the timing of this could be so perfect?

Detail of a woodcut

Detail of a woodcut

You must be logged in to post a comment.