SABU: Advocating with One Voice In 1971, Black students founded the Student Association for Black Unity, launching a 50-year tradition of advocacy on campus.

In the Fall of 1970, Washington and Lee enrolled 15 Black students. Neither the university nor the students were fully prepared for the changes required for success, but both parties were willing to make the effort to transform the university into a more diverse school. That work reshaped W&L, paving the way for more minority students, faculty and administrators on campus and inaugurating traditions observed today.

During their first year on campus, the students went through a series of racial incidents that emphasized to them that change was necessary. In 1971, they held meetings to discuss the best path forward and decided they needed an organization to fulfill their political, social and cultural needs, as well as provide protection when necessary.

Their solution was to form the Student Association for Black Unity (SABU), which became the voice of the Black student body. Its founding members included Walter Blake ’72; William Hill ’74, ’77L; Johnny White ’74, ’85L; Matthew Towns ’74; Johnny Morrison ’74, ’77L; Bobby Smith ’74; Thomas Penn ’74; Phillip Hutcheson ’74; Ernest L. Freeman III ’75; Robert Ford ’75 and Gene Perry ’75, ’78L.

Implementing Change

At the time, there were Confederate items displayed all over campus, and “Dixie” was played at many campus events. Under the guidance of “elder statesman” Walter Blake ’72, who became SABU’s first president, the students discussed their options and met with administrators, including President Robert Huntley ’50, ’57L, an important ally.

After their meeting, Huntley sent out a memo that prohibited playing “Dixie” on campus at any event. Shortly thereafter, a fraternity sent the group a note: “We’re going to play ‘Dixie’ [at an upcoming basketball game]. And we’d like you to come stop us.” The Black students and the fraternity attended the game on opposite sides of Doremus Gymnasium. In the end, the fraternity backed down. “That crystallized what it meant to have a group representing us in force,” Towns said.

Other efforts by Huntley and his administration included helping them acquire more furniture for their unofficial campus house and helping get Black music on the jukebox at the Cockpit, a small restaurant and hangout in the student center. “Those things may seem small,” said Towns, who succeeded Blake as SABU’s president, “but they mattered.”

The undergraduate campus, which integrated in 1968, could be openly hostile, not just to SABU but to Black students individually. Perry, SABU’s third president, had bleach poured under his door and his dorm room vandalized after he switched floors freshman year. SABU became “an all-encompassing entity” that could help with those sorts of incidents.

“We would meet, and we would talk about it,” Perry said. “It helped us to speak with one voice, and you could talk to another Black student who had a similar experience. A wealth of knowledge was brought to these meetings.”

Leaders in Action

In February 1972, SABU held its first Black Culture Week, anchored by keynote speaker Parren Mitchell, the first Black member of Congress from Maryland. At the end of the week, they sponsored the first Black Ball — one of the first black-tie events of its kind among universities in the area, most of which had been recently integrated.

Many founders remained involved with SABU for years; some who attended the Law School were active on campus for the better part of a decade. They continued to advocate and hold events, and in ways large and small, they changed W&L. For Towns, who helped change his school mascot from “Rebels” to “Chargers” in high school, their impact reflected their character.

“Just like the other students at W&L,” he said, “the Black students that came in the classes of ’74–’84 were already leaders in sports, student government or other organizations. SABU, like other organizations, helped to fortify the foundation that I received from my parents: be honest and hardworking, always try to do the right thing even when it’s not easy, and if things are not right, try to make them right.”

In SABU’s early years, Perry and White co-authored an admissions pamphlet on its behalf to help recruit Black students to W&L. It read in part, “Black students at all-male W&L are confronted by limitations on social life and the problems of being fully accepted in the small close-knit community that is Lexington. However, Washington and Lee gives the Black Brother who is progressive and has an eye on the future a start that is an asset for life.”

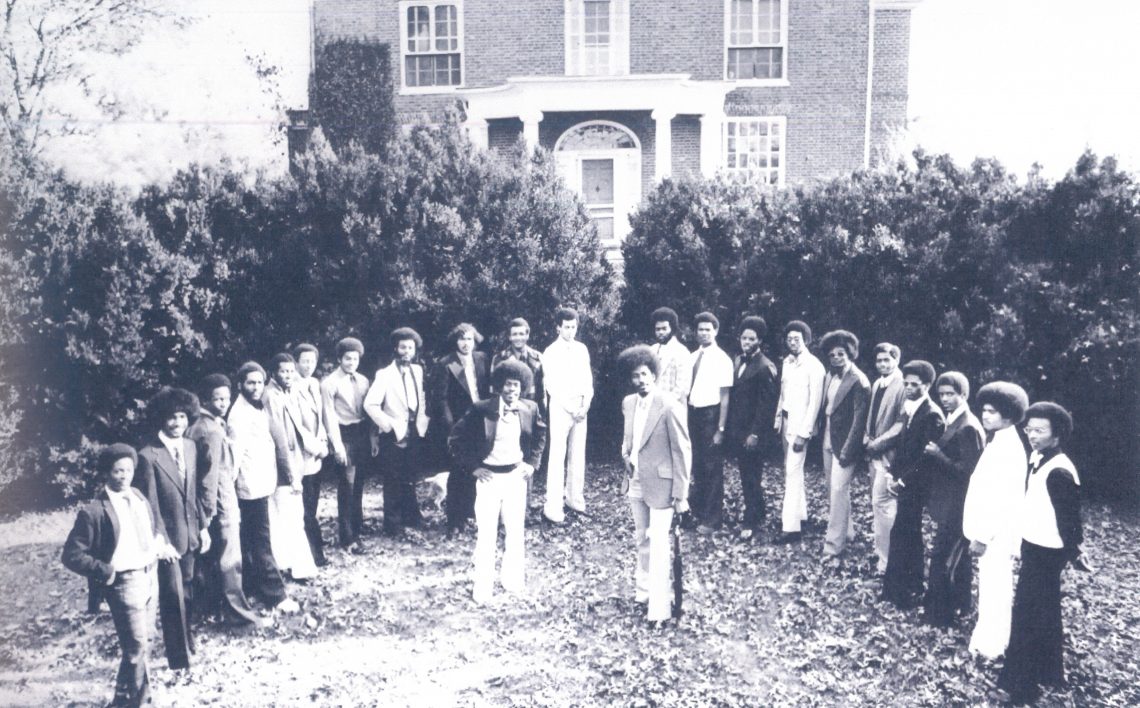

Above Photo: SABU group photo from the 1975 Calyx. Center: Gene Perry ’75, ’78L (left) and Ernest L. Freeman III ’75. From l. to r.: Pete Fisher ’78, Randal Johnson ’77, Derrick Abney ’78, Stephen Outlaw ’77, Robert Ford ’75, Stan Packer ’79, Dennis Mason ’76, Curtis Stewart ’78, Larry Crocker ’78, John Evans ’76, Ray Bowling ’78, Marshall Strickland ’77, Elliot Hicks ’78, Hoffman Brown ’77, Michael Brooks ’77, Talmadge Powell ’77, John X. Miller ’77, ’80L, William Harrison ’77, Eamon Cassell ’78, Aaron Lewis ’77, Al Boykin ’78. Not pictured: Anthony Perry ’77.

Photo right: Members of SABU, along with Jerry Darrell, a friend of the group and retired head of dining services, celebrating SABU’s 44th anniversary on campus.

If you know any W&L alumni who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

SABU Over 50 Years

1968: W&L’s undergraduate campus integrates. Two Black students, including future SABU president Walter Blake ’72, matriculate.

1970: W&L enrolls 15 Black students who become SABU’s founding core.

1971: SABU is founded to fulfill the political, social and cultural needs of Black students on campus and help ensure their safety.

1972: SABU hosts the first Black Culture Week, featuring speakers and events including the first Black Ball.

1973–1974: SABU assists in recruiting Black students; around 20 enroll after years of matriculating only one or two.

1985–1986: SABU is converted into the Minority Students Association (MSA); many early SABU alumni avoid campus for years in protest.

2010–2011: SABU re-forms as a separate entity from the MSA.