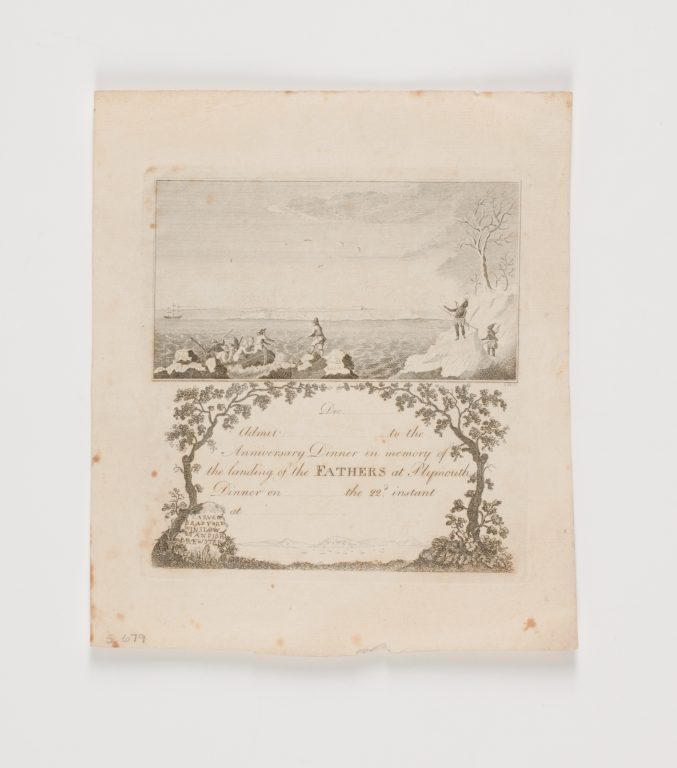

Serving Up a Story This 1820s plate in the Reeves Museum collection depicts the landing at Plymouth Rock, a likely myth that became a central story in the history of America.

Four hundred years ago, on December 21, 1620, the Pilgrims set foot in what they would come to call Plymouth. William Bradford, one of the leaders of the colony, described the event:

“On Monday they sounded the harbor and found it fit for shipping, and marched into the land and found diverse cornfields and little running brooks, a place (as they supposed) fit for situation; at least it was ye best they could find, and ye season, & their presente necessitie, made them glad to accepte of it. So they returned to their shipp againe with this news to ye rest of their people, which did much comforte their harts.”

Notice that Bradford does not mention the one thing that almost all of us think about when we think about the arrival of the Pilgrims: Plymouth Rock. The landing on Plymouth Rock, which is depicted on this plate made in the 1820s, is considered by many to be a key moment of American history. However, it is likely a myth. But myths are important; as archaeologist James Deetz, who excavated several sites in Plymouth, wrote, “historical myths of this kind provide a common shared sense of where we have come from as a people.”

The Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts on November 11, 1620, anchoring in what is now Provincetown harbor at the very tip of Cape Cod. Deciding that the Outer Cape was unsuitable for settlement, they sailed across Cape Cod Bay and, after the day of exploration by several of the colony’s leaders described by Bradford, chose the vacant Wampanoag village of Patuxet as the site of their new home.

There is a large rock on the Plymouth waterfront. However, most of the waterfront is sandy, so it is far more likely that the Pilgrims simply pulled their small boat up on the beach to disembark rather than clamber up onto a boulder, especially if the boulder was a large as the one depicted on the plate. So why do we think they landed on the rock?

The story emerged in 1741, when plans to construct a wharf around the rock led Thomas Faunce, a 95-year-old descendant of one of the early settlers, to protest that they were threatening to bury what “his father had assured him was that, which had received the footsteps of our fathers on their first arrival.”

It seems that the town fathers did not entirely bury the rock, but little seems to have been done with it until 1774, when, according to one 19th-century historian, “the inhabitants of this town, animated by the glorious spirit of liberty that pervaded the Province, and mindful of the precious relic of our forefathers, resolved to consecrate the rock on which they landed to the shrine of liberty.” While moving the rock to the Liberty Pole they had erected on the courthouse grounds, the patriots accidentally broke the rock into two pieces; in an attempt to put a positive spin on the calamity, they declared it to be symbolic of the splitting of the British Empire.

The rock became an important symbol of Massachusetts’s Pilgrim past and patriotic present. It became an important site for Forefathers’ Day, the holiday commemorating the Pilgrims’ arrival that is mistakenly celebrated on December 22, not the 21st.

Forefathers’ Day was celebrated with sermons, speeches and public dinners. It was the invitation to one of these dinners held in Boston in the late 1790s that seems to have served as the design for our plate. The invitation to the “Anniversary Dinner in memory of the landing of the FATHERS at Plymouth” was engraved by the Boston artist Samuel Hill. Below the scene of the landing is the text, with blanks left for the name, time and location of the dinner framed by trees and a view of Plymouth with the rock inscribed “CARVER/ BRADFORD/ WINSLOW/ STANDISH/ BREWSTER.”

The rock’s fame grew in the early 1800s, especially after the prominence given to it during the bicentennial celebration of the Pilgrims in 1820. The senator and orator Daniel Webster gave the Forefathers’ Day speech that year, proclaiming that:

“We have come to this Rock to record here our homage for our Pilgrim Fathers; our sympathy in their sufferings; our gratitude for their labors; our admiration of their virtues; our veneration for their piety; and our attachment to those principles of civil and religious liberty, which they encountered the dangers of the ocean, the storms of heaven, the violence of savages, disease, exile, and famine, to enjoy and to establish.”

Webster not only centered the rock in the Pilgrim story, but he centered the rock in the story of the history of the nation. Plymouth Rock became, according to the French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville, “an object of veneration in the United States.”

Of course, not all Americans venerated the rock or the Pilgrims. In 1836, William Apess, a member of the Pequot tribe, wrote that instead of celebrating Forefathers’ Day, “let every man of color wrap himself in mourning, for the 22nd of December and the 4th of July are days of mourning and not joy.” Also, as the nation expanded westward and the citizenry became more diverse, the New England-specific story of Plymouth Rock lost some of its resonance, replaced by a more universal celebration of Thanksgiving, first declared a national holiday by Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

But while the rock itself might have faded some in significance, commemorative plates like this one became more prominent among collectors. By the late 1800s, plates like this one were “perhaps more highly prized than any other historical Staffordshire wares, especially by all descendants from and lovers of the Pilgrims,” according to Alice Morse Earle, whose “China Collecting in America” was first published in 1892 and was an important guide for collectors well into the 20th century. That is probably why Euchlin and Louise Reeves acquired the plate for their collection, which came to Washington and Lee in 1967.

Plate made of pearlware (lead-glazed earthenware) by Enoch Wood & Sons, Staffordshire, England, 1820-1830.

Plate made of pearlware (lead-glazed earthenware) by Enoch Wood & Sons, Staffordshire, England, 1820-1830. Invitation to dinner in memory of the landing of the fathers at Plymouth

Invitation to dinner in memory of the landing of the fathers at Plymouth

You must be logged in to post a comment.