‘Uncharted Territory’ As city manager of New Rochelle, New York, Chuck Strome ’80 is at the center of New York's pandemic.

By Jeff Hanna

April 1, 2020

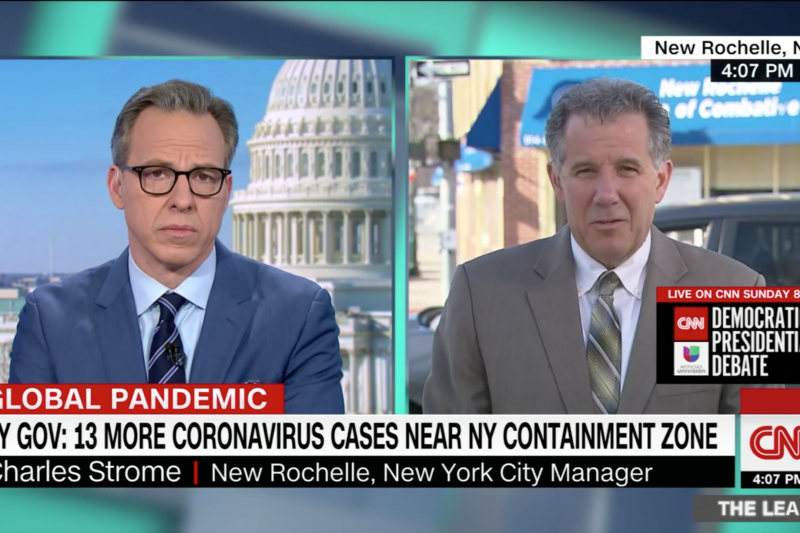

Chuck Strome ’80 (right) was interviewed by CNN’s Jake Tapper.

Chuck Strome ’80 (right) was interviewed by CNN’s Jake Tapper.“The people of New Rochelle have dealt with this extremely well. I think we’ve been a good example of what people can and should do in this case.”

~ Chuck Strome ’80

As city manager of New Rochelle, New York, for the past 18 years, Chuck Strome ’80 had helped steer the city through numerous disasters, including hurricanes, nor’easters and blizzards.

Then came COVID-19, and nothing Strome had faced could have prepared him for what would happen when New Rochelle became ground zero for the initial outbreak of the virus in New York state.

On March 2, one of New Rochelle’s 80,000 residents, a man in his 50s, tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19. This was seen as the first case of community spread, which means the source of the virus was unknown. Within a week, more than 50 cases of COVID-19 could be linked to the initial patient. These included family members, neighbors, friends and friends of those friends.

“We know how to respond to challenges like the weather-related disasters because those are fairly well defined, and we’ve done them,” said Strome in a telephone interview from his office in New Rochelle’s City Hall on March 23, three weeks after the first case was discovered there. “In New York state, we don’t have a public health function per se as a city. Consequently, we were scrambling to deal with what the state and county health folks were telling us to do.

“Meanwhile, residents were calling and wondering and worrying about their health. Needless to say, it’s been uncharted territory.”

The initial patient in New Rochelle was a member of the Young Israel of New Rochelle synagogue, which has about 1,000 members. In the week before testing positive, he had attended three events at the synagogue — a bat mitzvah, a funeral and a general service.

“Essentially, he was in contact with the entire synagogue during that week. He became the index case for our cluster and thrust us squarely into the center of the crisis,” said Strome, explaining how the city teamed with the Westchester County Health Department to contact members of the synagogue, all of whom voluntarily self-quarantined for two weeks.

“If any of the members developed symptoms, they were tested,” said Strome. “It turned out that more than 100 of them did test positive. As it got bigger, the state government came in and created a containment zone — a one-mile radius of the address of the ‘index patient.’ All the schools in that were closed, business were closed except for restaurant takeout, large gatherings inside the area were prohibited, and satellite testing areas were set up.”

The containment zone in New Rochelle was a preview of what was coming. A week later, all of New York essentially became a containment zone, and many areas throughout the country soon followed suit.

When the National Guard arrived in New Rochelle on March 12, attention already being paid to the city increased dramatically.

“People hear the National Guard is coming, and they immediately think you’re being put under a state of military law. That was not the case, of course,” Strome said. “They came to do two things. First, they came to help distribute food to vulnerable seniors and students who are on the free lunch program in the schools. Secondly, they cleaned many of our buildings — houses of worship, City Hall. That was their role, and we needed to make that clear to everyone. They weren’t in tanks. They weren’t armed.”

As if the situation were not already stressful enough, things got crazier once Strome began juggling appearances on CNN, Fox News, MSNBC and the BBC, along with local media outlets.

A journalism major at W&L, Strome had spent eight years working on a local radio station in Westchester County while also doing freelance for NBC radio and CBS-TV in New York City. Consequently, he was not unaccustomed to dealing with media, but this was different.

“I suddenly found myself talking with Jake Tapper of CNN and Harris Faulkner of Fox News, for instance, and this was something I’d never experienced before and never dreamed I would be doing,” Strome said. “My friends from W&L would say they knew I always wanted to be involved in something like this, but it would be sports and I’d be on the other side of the camera.”

Strome praised the way residents in his city, particularly members of the synagogue, have performed under the circumstances and believes New Rochelle has served as a good model for the country.

“The people of New Rochelle have dealt with this extremely well. I think we’ve been a good example of what people can and should do in this case,” Strome said. “We’re vastly smaller than New York City, which is essentially unmanageable, but when I see people congregating in a park in the middle of this or kids on the beach in Florida, it’s mind-boggling for me.”

As of March 23, New Rochelle was officially reporting 225 confirmed cases. Strome admits that number is undoubtedly misleading because of the same lack of testing that has been problematic nationwide. Still, he said, it’s clear the containment zone made a difference because most of the cases in New Rochelle were confined to the area where the virus first started and there had been a leveling off after three weeks.

The New York Times highlighted New Rochelle in a March 28 story and showed how the curve had begun to flatten in the containment area. The Times said state and local health officials warned that it was too early to declare victory but that they were encouraged by how the measures first adopted in New Rochelle seemed to be showing success.

Strome said that while the data from New Rochelle were somewhat comforting, the challenging environment is bound to continue for weeks, at the least, and that when the crisis does eventually end, the residual effects are going to be hard to calculate.

One silver lining for Strome is how governments have shown they can collaborate under such dire circumstances. He’s been in city government in New Rochelle for 31 years, first as director of emergency services, then assistant city manager and city manager since 2002. His roles have all been non-partisan. He is appointed, not elected, but is no stranger to the political battles that often lead to inter-governmental skirmishes.

“I have been gratified by the way the state, the county and the local governments have worked together because that has not always been the case during normal times,” Strome said. “We’re all trying to put our heads together and do the best we can for our citizens.”

Strome said he had not been tested and had no plans to be tested. “I suppose if I went down and really pushed it, saying ‘I’m city manager and would like to be tested,’ I probably could be. But given the shortage of tests, they really need them for people who show symptoms — more than mild symptoms, in fact,” he said. “Those are the people who should be getting tested because there aren’t enough test kits at this point. So I’ve not been tested, but I feel wonderful.”

Strome became interested in city government because that was one of his beats at the radio station. He took an entry-level position and went to graduate school at nearby Pace University for a master’s in public administration. He is former president of the New York State City/County Managers Association and past president of the Municipal Administrators Association of Metropolitan New York. He’s won numerous awards from community organizations, including the New Rochelle Chamber of Commerce, the Calabria Society and the Boys’ and Girls’ Club of New Rochelle.

If you know any W&L alumni who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

You must be logged in to post a comment.