What We Lost: Remembering Vietnam 50 Years Later W&L alumni look back at the Vietnam War and how it changed them.

Three dozen members of the Class of 1967 crowded the stage in Stackhouse Theater on Alumni Weekend this past April. As the audience looked on, retired Navy SEAL Bill Wildrick ’67 thanked each man on stage for his service, presented him with a black-and-gold pin, and gave him a crisp salute.

The occasion commemorated much more than a 50th class reunion for these alumni — it marked a half-century since they were forced to face a future they could not have anticipated as happy-go-lucky teenagers.

“I went to Vietnam as a 22-year-old boy,” said Jim Oram ’67, “and came home as a 24-year-old man. I was a completely different person.”

The United States’ official commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Vietnam stretches from 2012 to 2025. Although W&L does not have detailed records of the number of alumni who served, many classes that have already celebrated a 50th reunion, and some that have yet to reach that mark, are likely to include Vietnam veterans.

Dr. William Sledge ’67, a psychiatrist who studied the effects of imprisonment on Air Force POWs during and after Vietnam, took part in a panel discussion with other veterans that preceded the pinning ceremony at W&L in April. Later, he noted that while some veterans still prefer to leave their stories untold, many have grown increasingly comfortable reminiscing as the decades have passed, particularly with their families and one another.

“I think that when you get older, it doesn’t matter whether you have been in a war or not, you start thinking about your life in a different way,” he said. “You particularly want to tell your family about it, you want to revisit it … so you remember stuff, and you value the opportunity to let people listen to it.”

‘What the Hell Was Happening’

In the mid-1960s, the conflict in Vietnam was a topic on the nightly news and in classrooms at W&L, but not at parties or on the football field. As Mac Holladay ’67 put it, “I think people were aware. The build-up had started, but it had not reached a fever pitch yet. We just didn’t know very much about it because we were all concentrating on our studies and going on about the future.”

There were a few exceptions: In the basement of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity house every night, Alex Jones ’68 and Barry Crosby ’68 used to watch Walter Cronkite deliver the “CBS Evening News.” “Barry and I shared something that not many other people in my fraternity at the time seemed to,” Jones said, “which was a concern and interest in what the hell was happening in Vietnam.”

As the situation escalated, however, plenty of students began to feel anxious. Many had already planned to attend graduate school, get married, or both, which could result in a temporary deferment prior to the draft lottery of 1969; those who hadn’t considered those options began to regard them with greater interest. Still others had medical deferments, and there were a few conscientious objectors.

A percentage of each class joined the ROTC at W&L, including Oram, who followed the advice his father gave him as they drove to Lexington for his freshman year. Participating in ROTC allowed Oram to be commissioned as a second lieutenant after graduation, but that was still no guarantee of safety during Vietnam. He ended up as an Army Ranger commanding a company in the 101st Airborne Division, otherwise known as the “Screaming Eagles.”

In another effort to prevent being drafted and sent straight to the rice paddies as infantrymen, some students applied for officer training programs. Jones, Holladay and Wildrick were accepted to Navy Officer Candidate School, after which Jones became a naval officer, and Holladay became a search-and-rescue pilot. Wildrick, who stood out as a swimmer and runner at W&L, became a Sea Air Land commando before most people had ever heard of a Navy SEAL. (He retired in 2005 as the last active-duty SEAL platoon officer who served in Vietnam.)

Bruce Rider ’66 went through Air Force Officer Training School (OTS), but not before facing a dilemma: He had already started classes at Princeton Theological Seminary when he got the call about his application to OTS. Most of his fellow students at Princeton wanted to stay safely ensconced there, but every generation of Rider’s family, dating back to the Revolutionary War, had served in the military.

“I felt an obligation to be part of the family tradition to serve in the military,” he said. “I did not want to start a career in the ministry just to avoid service.”

It is estimated that 25 percent of the forces in Vietnam were drafted, and that included some W&L alumni. One of those men was Walter “Buddy” Nicklin ’67, who considers himself fortunate because he was sent to Europe to work as a chaplain’s assistant and never made it to Vietnam. On the occasion of his 50th W&L reunion, he wrote an essay for the May 5, 2017, edition of The New York Times, recounting the personal anxiety and moral questioning that the draft created for him.

Barry Crosby, the young man who sat in the glow of that fraternity house TV with Jones as they watched the news, was not so fortunate. Jones was on a U.S. Navy ship in the Gulf of Tonkin when he found out that Crosby had been killed. He was one of 18 W&L alumni who died in Vietnam.

“Whenever I go anywhere near the Vietnam Monument in Washington, I always visit his name,” Jones said. “It was a personal loss that, I think, a lot of the people who knew Barry felt very powerfully.”

Cultural Divide

The Vietnam War was a frustrating and difficult one to fight, in an inhospitable climate with unfamiliar terrain. The cultural divide between Americans and Vietnamese made it harder to distinguish friend from foe. Guerrilla warfare made for a particularly deadly and dirty fight.

Washington and Lee alumni were among the men who put their lives in danger for a war that sometimes felt pointless. They went on intelligence-gathering missions, set up ambushes, marched through jungles pocked with punji pits, and watched comrades impaled on sharpened, feces-covered stakes. They dodged bullets, rescued airmen from downed planes, and had their Jeeps blown up by kids with C-4 explosive.

That’s merely a sampling of the tales they tell, which are usually short on the most troubling details. Of course, it does not begin to encompass the memories that will stay buried in gray matter for the rest of their lives.

Oram starkly summed up the reason so many veterans have kept mum about their service: “There are some things that are too scary to even recall and try to talk about. Some of us might have done stuff we’re not very proud of. When you are secretly scared to death and you are a ranger commando, you aren’t going to tell anybody.”

When these soldiers came home, it was not to the victory parades and hero worship with which World War II veterans were met — it was to a country that was deeply divided over the war, and that offered few support systems. Veterans were alternately spit upon, goaded into fistfights, and ignored.

“Vietnam was full of ambiguity and misunderstanding, and a lot of conflict in the general culture about whether we should be fighting this kind of war,” said Sledge, the psychiatrist. “We didn’t win it, we lost it. And a lot of people lost their lives. There is a bitter sense of loss and ineptitude on our part and on the part of politicians.”

As a result of his experience as an Air Force intelligence officer, Rider went legally blind within a year of coming home. Other fallout from the war included a lost job and a failed marriage, and he remembers feeling incredibly alone.

“This is hard to conceptualize, but something died inside of me,” he said. Although he was proud of his service, he said, “There was this part that was just dark and angry and resentful.”

Most veterans had to come to terms with the U.S. government’s handling of the war, and solidify their own opinions about it, which sometimes changed drastically after they came home. Holladay, who now suffers from peripheral neuropathy and COPD as a result of his exposure to Agent Orange, decided within the last decade to read everything he could find about the war. “I have learned a lot, and I certainly understand that we were misled and lied to, and that if there was a way to win, we did not do that,” he said. “We didn’t try to do that, I don’t believe.”

Some vets also harbor feelings of guilt for reasons they may or may not be able to articulate. “I can tell you that goes all the way up to guys who won the Medal of Honor but feel guilty because they survived and the other guys didn’t,” Oram said. “Others feel guilty because they didn’t get into combat. I’m in the middle: I did what I did and I survived, and I feel guilty that I couldn’t do more.

“That is a common thread that goes all the way back to the beginning of mankind. The only ones who don’t feel guilty are the ones who got killed, and that’s just because they can’t.”

A Desire to Serve

No matter their military branch, service experience, or political leaning, most of the alumni veterans interviewed for this article said that the war, as difficult as it was, spit them out as better people than they had been when they went in. They seem to share a lifelong desire to serve their communities and their country.

Holladay, haunted by an image of naked, hungry children picking over a garbage dump in Indonesia, remembers thinking, “If I can get home safely, I want to try and make sure nobody in my hometown of Memphis is ever looking for something to eat.” He devoted his entire career to community and economic development not only in Memphis, but also across the nation.

Sledge continued his research with POWs and became one of the first psychiatrists to publish on what is now known as post-traumatic growth. Rider is involved in multiple civic activities, including veterans’ organizations, fraternal groups, the historical society, and his local library. Jones is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. Wildrick became an instructor who helped to set up reserve SEAL support commands on the East and West coasts, providing the closest link between active and reserve forces in the 30-year history of the Naval Special Warfare Reserve.

Oram has served on the board of directors for the child services organization that arranged his own adoption when he was a baby. He is also an elected supervisor in his township, and is involved in the local veterans’ organization and other nonprofits. “I realize even more, now that I’ve started talking about Vietnam, that my whole life has been building toward this crescendo of service,” he said.

Some of these veterans recognize that if it had not been for the war, they may never have been exposed to diversity. “We are all created equal,” Holladay said. “I relied on people of all colors and shapes and attitudes during my five years of service, and it certainly changed my outlook on diversity and the world.”

“I think the war was a good experience in terms of exposing me to things I otherwise wouldn’t be exposed to, and it also politicized me,” Nicklin said. “When I was at W&L, I was more interested in poetry and personal experiences and beautiful sunsets, not really politics. I thought politics was kind of a waste of time and for silly people, but the Vietnam War and being drafted made me understand that politics is always what society is all about.”

Washington and Lee has worked with alumni to create opportunities for Vietnam-era graduates to return to campus and reconnect over their shared experiences. In 2009, the university held a well-attended Alumni College program titled “Vietnam: A Retrospective.” This year’s Alumni Weekend panel discussion, which featured Holladay, Sledge and Oram, along with historian and author George Herring, brought veterans together to reminisce about both the war years and their W&L careers.

“I thought one of the things that was wonderful about our seminar was the opportunity to hear different perspectives and see the interest that we all have in those different perspectives of all the people who served,” Holladay said. “It was personal for each one of us.”

The Alumni Magazine welcomes additional memories from W&L alumni about the Vietnam War Era, and may publish some of those comments in a future issue or on the website. Whether you went to Vietnam or not — and for any reason — we are interested in hearing about your experience. Please email us at magazine@wlu.edu.

Eight Days in May

During the Vietnam Era, college campuses across the country became hot spots of political unrest. Although W&L was not completely insulated from this, its campus did remain relatively quiet — until May 1970. On May 4, Ohio National Guard members shot four unarmed students during a protest of the Vietnam War at Kent State University. Nationwide, campus protests exploded in size and intensity. At W&L, the shootings sparked a week of rallies, meetings and debates remembered today as “Eight Days in May.”

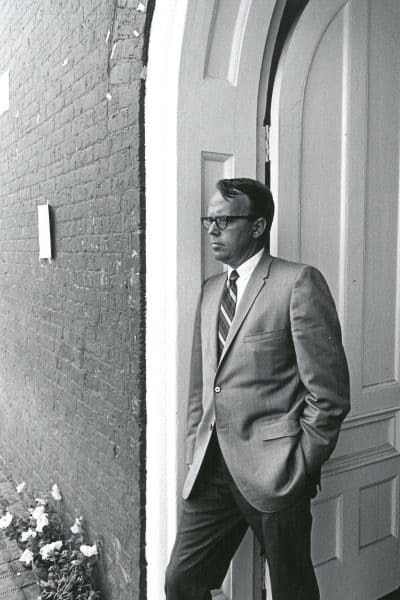

Tuesday, May 5: From 400 to 500 students gather on the lawn in front of Lee Chapel for a rally. Some suggest boycotting classes or calling for the university to close. President Robert E.R. Huntley ’50, ’57L leaves his Law School class to address the crowd, warning against violence and encouraging those with opposing opinions to share them civilly with one another. He receives a standing ovation. That night, the SEC adopts a resolution to call attention to activities planned for the next day, “Freedom Day.”

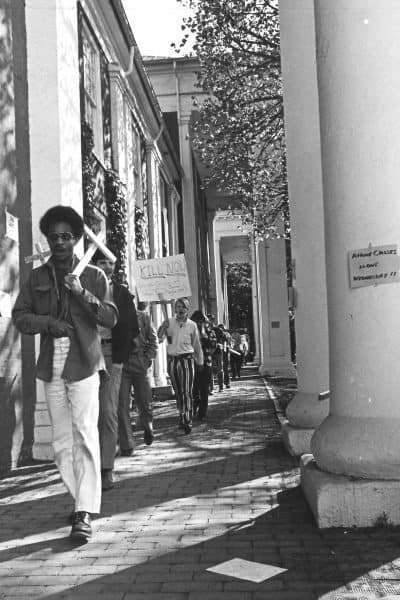

Wednesday, May 6: While many students attend classes as usual, 30 to 40 picket on the Colonnade for two hours. About 200 students travel to a rally in Charlottesville. The student body president, Marvin “Swede” Henberg ’70, calls for a student assembly on May 8.

Thursday, May 7: Concerned students meet with Huntley to request relief from academic schedules to participate in the student movement. About 100 students gather in the Cockpit, as the University Center tavern was known, for an open forum. This results in a resolution to close the university for the year so students will be free to participate in national events. The faculty declines to cancel classes but allows students to submit a request in writing and receive an incomplete grade until Sept. 30, when the “I” will be replaced by an “F” if work is not completed.

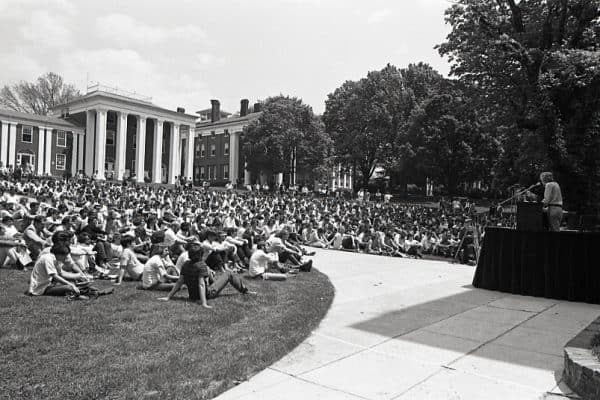

Friday, May 8: About 900 students meet in front of Lee Chapel, where Henberg presents the resolution and invites discussion. The vote is postponed until Monday.

Saturday, May 9: Reunion Weekend (and the annual Alumni Association meeting) takes place. Many students travel to Washington for large demonstrations, while others, half-dressed and unshaven, hang around in tents they’ve pitched on campus. Students and alumni engage in constructive discussions about the war, and alumni praise Huntley for his handling of the previous week’s unrest.

Sunday, May 10: Students hold a memorial service in the University Center (now Evans Hall) for the four students killed at Kent State. The SEC endorses the resolution to close W&L but wants students to be able to continue classes if they wish. Debate continues into the evening.

Monday, May 11: Some 78 percent of the student body votes to cancel classes, retroactive to May 6 and through Fall Term. Faculty gather that evening, and many express sympathy for the student viewpoint. Some support university closure, but Huntley refuses, citing obligations to the trustees and university charter to keep the school open. Instead, faculty reiterate their action of May 7, saying students who wish to take incomplete grades must inform them in writing by May 21. Upset students boycott classes.

Tuesday, May 12: Students hold an assembly on the Front Lawn at 8:45 a.m. and read a statement condemning the faculty motion. Huntley holds a student assembly at noon, during which he assures students that ‘lack of agreement” from the faculty and administration does not equal a lack of concern. “I must say I believe you have succeeded in bringing this student body into a sense of community, a sense of willingness to talk, a sense of willingness to share deep conviction, a sense of dedication to something higher than self,” he tells them.

Source: “Washington and Lee University, 1930-2000: Tradition and Transformation” by Blaine A. Brownell ‘66

BY THE NUMBERS

9.2 million Americans served in the military during the Vietnam Era

2.7 million Americans served in Vietnam (rather than at home or in another theater)

58,220 Americans were killed in the war

18 Washington and Lee University alumni were killed in the war. They were:

William Michael Akers ’58

Charles Christopher Bonnet ’65

William Caspari III ’58

Robert Barry Crosby ’68

Jon Price Evans ’37

Robert Morrow Fortune ’67

Henry Poellnitz Johnston Jr. ’70

Leo John Kelly Jr. ’66

John Peter Luzis Jr. ’70

James Howard Monroe ’66

Thomas Alexander Nalle Jr. ’54

Ronald Oliver Scharnberg ’63

Louis Otey Smith ’58

Jay Webster Stull ’60

Frederick Nicholas Suttle Jr. ’67

Walter Ludman Toy ’63

Scott Mitchell Verner ’65

James Schenler Wood ’63

More Memories from W&L Vietnam Vets:

Mac Holladay ’67 on the dangers of war:

“I had all kinds of experiences. I tied my seaplane up to a palm tree, rescued people from a downed aircraft on two B52 crashes off Guam, which was tragic. I had a fire in my H34 — a crewman we affectionately called Pineapple put it out at great risk to himself. Once, I was trying to rescue a man in a typhoon, and the helicopter turned virtually upside-down. I got shot at a few times. But I certainly was not in harm’s way like [Jim] Oram and the guys on the ground were.”

Dr. William Sledge ’67 on the prisoners of war he met through his research:

“First, I was enormously touched by the humanity of these people and was very proud to be associated with them. Before them, I didn’t think they were anything special, just people who were at the wrong place at the wrong time. But these were everyday folks who discovered what they were made of and were proud of it, and I was enormously impressed by them.”

Jim Oram ’67 on fear of dying:

“It never occurred to me that I could be killed. That wasn’t on my radar until I got over there, then it got on my radar pretty quickly. I even said to my wife, ‘You don’t have to worry about me. I’m not going to be killed.’ But once I got there, I didn’t have a fear of dying so much as a fear of letting my soldiers down. And I can’t lie, there was also an element of excitement after every incident. It’s like jumping out of an airplane.”

Bill Wildrick ’67 on his children and the military:

“The kids don’t really ask about Vietnam. They used to love to wear the T-shirts and paraphernalia. I didn’t get any one of them to go into the military. The closest thing was that my daughter was in the Girl Scouts. I talked to her about maybe being an intelligence officer, and she finally said, ‘Look, Dad, I’ve heard your spiel, and I appreciate what you did, and I support you 100 percent, but if I develop an interest, I’ll let you know.’”

Bruce Rider ’66 on war:

“Anybody who is in favor of war has really not been in one. I think we have a responsibility to build peace in our lives where we are. You try to live a better life as a result of warfare and you tend to have fewer strongly held views … most rigid people just don’t have the experience or the appreciation or the empathy that war survivors should have.”

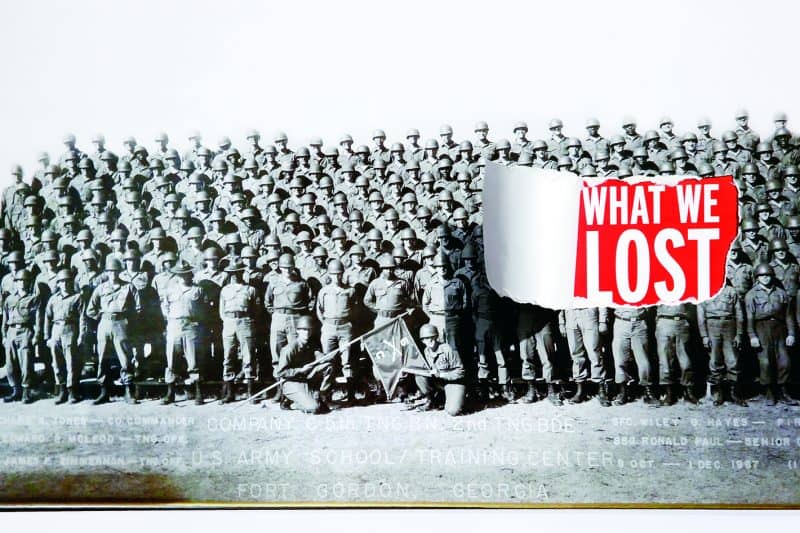

Walter “Buddy” Nicklin’s training company photo

Walter “Buddy” Nicklin’s training company photo

Students picket along the Colonnade in May 1970 during “Eight Days in May.”

Students picket along the Colonnade in May 1970 during “Eight Days in May.” Students gather on the lawn during “Eight Days in May” 1970 to hear student body president Marvin “Swede” Henberg ’70.

Students gather on the lawn during “Eight Days in May” 1970 to hear student body president Marvin “Swede” Henberg ’70. President Robert Huntley ’50, ’57L looks on from the Colonnade as students

President Robert Huntley ’50, ’57L looks on from the Colonnade as students

You must be logged in to post a comment.