W&L Law Unveils Tribute to First Female Graduates A new installation at Washington and Lee University School of Law celebrates the first female graduates of the law school.

Today, women make up half of the student body and faculty at W&L Law, so it is hard to imagine what trailblazers like Amber Lee Smith and Sally Wiant found when they matriculated with the first class of women in the early 1970s.

The University made the decision to allow female students rather late in the year, Smith ’75L said, recalling her admittance. Her father, an alumnus of W&L, had been keeping tabs on the controversy through a friend on the inside. After the decision was made, her father’s “spy,” as Amber said, quickly sent an application over in the mail.

Later, Smith, along with six other women, formed the first co-ed class in W&L Law’s history. It was 1972.

“I used to go on and on about the halls, the portraits,” Sally Wiant ’78L, a member of the first class of women and now emeritus professor, said. “They are all important portraits,” she continued, “but it would seem that there have been enough of us [women] that have made contributions to the school, the profession, the bar, the bench.”

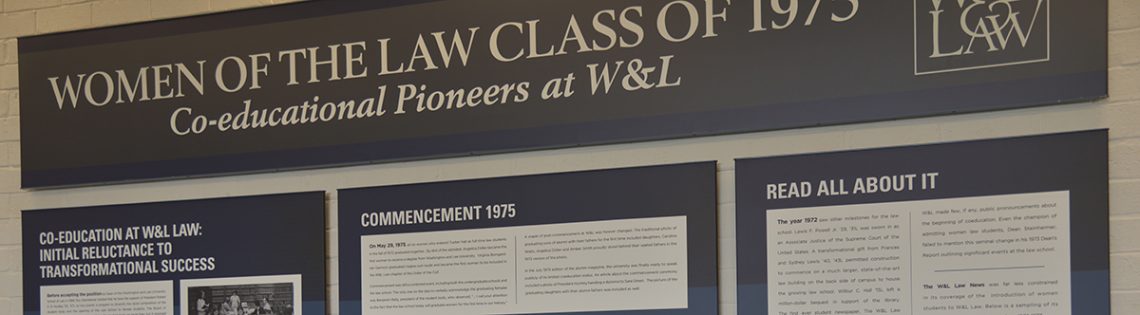

Now, in addition to honoring the many male leaders of the school, the walls pay tribute to the first women of W&L Law with a new installation in Lewis Hall. The display, in the Moot Court Lobby, includes photos of their time at the law school, news clippings about coeducation, and coverage of their graduation.

When speaking about that first year, both Smith and Wiant laughed about how logistically unprepared the law school was to meet their needs. “When we arrived, we just arrived,” Wiant said.

“A lot of things weren’t thought through clearly,” Smith agreed.

For instance, Smith said that, before they arrived, there was a small, single-stall women’s bathroom for staff. But after women were admitted, the school switched the women’s bathroom with a faculty bathroom down the hall, since it had more stalls and space. They hastily put up paper signs to indicate the change: “STOP: this is NOT the women’s bathroom,” one said. And “STOP: this is NOT the faculty bathroom,” the other said.

“We put a big potted plant in front of the urinal,” Smith laughed, adding that, if the female students wanted to have a meeting, they would just go to the bathroom. The athletic facilities at the school didn’t accommodate women either, said Wiant, who as a student had wanted to swim for exercise.

“But there was a huge tradition where the guys swam in the buff,” she recalled. Plus, everyone who wanted to swim had to enter through the men’s locker room. “It took the athletic committee a year to work that out.”

That first class experienced some hardship and prejudice from classmates, Wiant and Smith said. A man at a party once told Smith that, when he signed up for W&L Law, he was under the impression that he wouldn’t be attending school with women.

Smith also didn’t like standing out wherever she went. Before going to law school, she had attended an all-women’s college, and she missed the freedom that she experienced there as an undergraduate while walking on the W&L campus.

“It was like going to class in a fish bowl,” she said. “You couldn’t be anonymous or even unremarked.”

One of their female classmates had a hard time getting an apartment, too, Smith recalled, because the landlords didn’t want to be responsible her getting home by ten o’clock.

There were no female professors, no role models to look up to. Pantsuits were scandalous. Wiant remembered a colleague of hers at a library in Texas getting fired—on the spot—for showing up to work in a pink pantsuit. She herself experienced a lighter kind of disdain for pantsuits.

“If I saw a certain professor walking on the colonnade—if I had a dress on he would say hello, if I had a pantsuit on he would act as if I was air.”

Because she worked in the law library while studying, Wiant graduated later than her other classmates. When she became the director of the law library law after graduation, she remembered being told that she had just doubled the number of women on the faculty.

Still, Wiant said she made close male friends, and Smith described her professors as supportive, “or at least not anti-female.”

“We were proving that, academically, we could be there,” Smith said. It wasn’t always easy—law school is intimidating no matter what your gender is, she qualified—but being a woman added a whole different set of considerations.

“[But] when you are 21, 22-years- old, you really believe that you can do anything,” she continued. “If you are given this opportunity to prove that women can do things—of course you’re going to do it— so I did.”

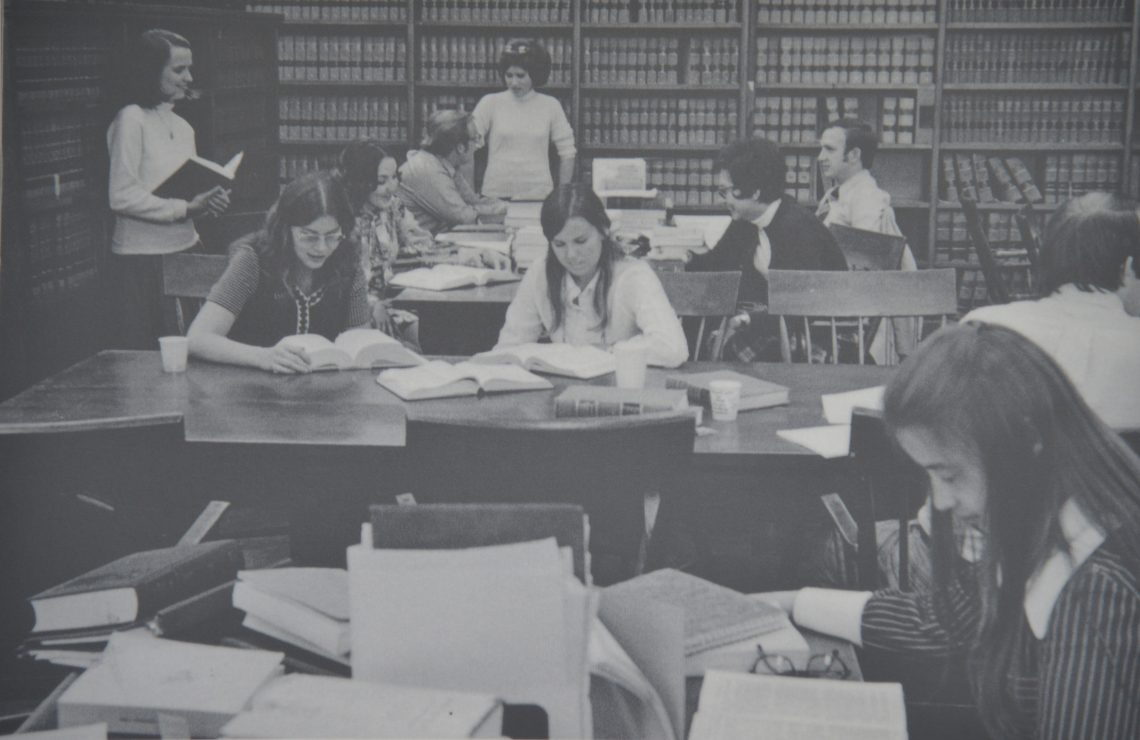

All of the women of the Class of 1975 studying in the reading room of the Tucker Hall law library.

All of the women of the Class of 1975 studying in the reading room of the Tucker Hall law library. Sally Wiant

Sally Wiant

You must be logged in to post a comment.