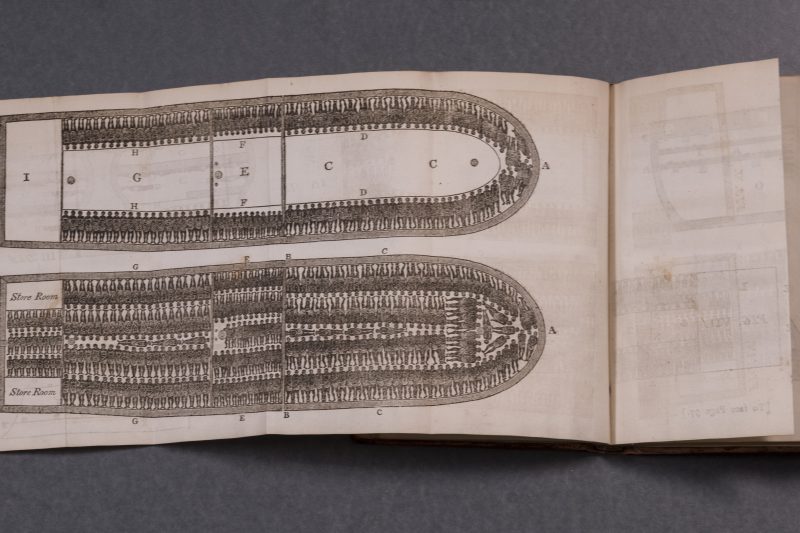

A Plan to Sink Slavery A plan of the slave ship Brookes that was used to advance the cause of abolitionists has been acquired by the Reeves Museum at Washington and Lee University, where it will complement a collection of abolitionist ceramics.

The movement to abolish slavery was one of the earliest social movements to use objects decorated with provocative imagery to advance its cause. And no image used by abolitionists was more provocative or became more recognizable than the plan of the slave ship Brookes.

The plan shows 451 African men, women and children crowded onto the lower deck of the Brookes, a 297-ton ship which made regular voyages between Liverpool, the Gold Coast of Africa (modern-day Ghana) and the Caribbean in the 1780s and 1790s. The plan was developed by the Plymouth chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1788, and it was based on research and observation of the ship. The image was revised by the London chapter (creating the version of the image seen here) and reprinted throughout Britain, Continental Europe and the United States. The plan would, according to one historian, “prove to be among the most effective propaganda any social movement has ever created,” and it became the defining symbol of the cruelty of the Middle Passage that transported millions of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas.

According to Thomas Clarkson, one of the founders of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, the plan was “designed to give the spectator an idea of the sufferings of the Africans in the Middle Passage.” While the slave trade was an important part of the economy of Great Britain, Continental Europe and the United States, for the vast majority of white people, it happened out of sight and was therefore out of mind. The stark image of people shackled together with “not so much room as a man in his coffin” made unavoidably visible the fact that slave ships were places of cruelty, violence and death.

As horrible as the image is, its depiction of anonymous, motionless figures paints an incomplete picture of what it was really like in the crowded decks of a slave ship. Olaudah Equiano, one of the few Africans to write about his experience on the Middle Passage, comes closer with his description: “the closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smell, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died.”

Copies of the plan were sent to political leaders, clergymen and other influential citizens throughout Britain, Continental Europe and the United States, where they were displayed in public; the Edinburgh chapter of the society instructed members to “paste up a plan of a slave ship wherever they think it will be seen by many.” The stark and disturbing image succeeded in raising public awareness; according to Clarkson, “this print seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it, and as it was therefore very instrumental, in consequence of the wide circulation given it, in serving the cause of the injuring Africans.”

This edition of the plan appears in “Abstract of Evidence delivered before a Select Committee of the House of Commons in the Years 1790 and 1791 for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.” A distillation of the hundreds of pages of evidence presented to Parliament in favor of abolishing the trade, it includes text detailing the horrors of the slave trade, a map of the West Coast of Africa from which most enslaved people were bought, and the plan of the Brookes.

This 155-page booklet is considered one of the most widely read anti-slavery publications ever published. Thousands of copies were printed, and it was widely circulated in Britain and the Americas; one observer in the north of England noted that Thomas Clarkson was “disseminating the Abstract throughout the realm I trust with such effort that it will grow up and ripen to an abundant harvest.” Copies even made it to Jamaica, where nervous colonial officials noted that “perhaps nothing has contributed to the dissemination of these notions [of freedom] among our Negroes than the publication of the witnesses’ examination before the House of Commons, most industriously sent out by persons in England, and explained to our Slaves by free people of colour.”

The society’s attempts to convince the British Parliament to abolish the slave trade were not immediately successful. While their testimony and advocacy convinced many, it was not enough to overcome the entrenched interests in preserving the status quo (which was quite profitable for many in Britain and her Caribbean colonies) or the fears raised by the revolutions in Haiti and France. However, the issue, once raised, could no longer be ignored. Attempts resumed in 1807 and succeeded in abolishing the slave trade in that year.

“Abstract of Evidence” was recently acquired by the Reeves Museum of Ceramics. While we do not actively collect books or other printed material, the Reeves has one of the largest collections of ceramics made for the anti-slavery movement in existence. Adding this important image and text will help us better interpret the movement to abolish the slave trade and slavery itself, as well as to interpret how activists use objects to advance their cause.

This plan of the slave ship Brookes was used by abolitionists to further their cause.

This plan of the slave ship Brookes was used by abolitionists to further their cause.

You must be logged in to post a comment.