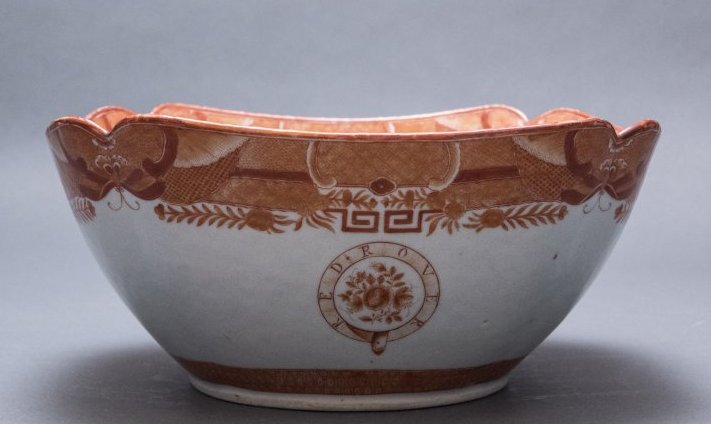

A Salad Bowl with a Sordid Past This elegant bowl, which is part of W&L's Reeves Collection, can be traced back to the Opium War of 1839-1842.

Drug wars may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you see this elegant and elaborately decorated piece of Chinese export porcelain. But this bowl, from a large service emblazoned with the name of the ship Red Rover, is intimately connected to the smuggling of opium from India into China in the 1830s and the first Opium War fought between China and Great Britain from 1839 to 1842.

Red Rover was a 97-foot long, 245-ton, three-masted ship built in Calcutta, India, in 1829. Named after the swashbuckling pirate in James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Red Rover,” she was the first of what became known as “opium clippers,” which were fast sailing ships that smuggled opium from India to China.

Based on American clipper ships designed during the War of 1812, Red Rover was built for speed, with a sleek hull, flush deck and raked masts. These features allowed her not only to go fast, but also to sail close into the wind, allowing her to sail from India to China even during the winter monsoons that blew from north to south. On her maiden voyage in 1830, she sailed from India to China and back in just 86 days, beating all previous records. She made two other voyages to China that year, a schedule she continued most years until she was lost at sea in 1853.

For most of her life, Red Rover belonged to Jardine, Matheson & Co. The company had been founded in 1832 by the Scotsmen William Jardine and James Matheson, and was the leading merchant house involved in the lucrative but illegal opium market; by 1834 they were responsible for one-third of the opium smuggled into China. They were also among the leading proponents of “free trade,” which to them meant forcing China to ease trade restrictions and open more ports to foreign merchants, by force if necessary.

Opium, a narcotic that Chinese addicts mixed with tobacco and smoked, had been illegal in China since 1729. However, British and American merchants smuggled it into China starting in the early 18th century. The amount grew each decade, from around 4,000 chests a year (a chest would hold about 140 pounds of the drug) in the early 1800s to 10,000 chests in the 1820s. That figure was up to 19,000 chests in 1831-32, and 40,000 in 1838-39.

This made vast fortunes for a few British, American, Indian and Chinese merchants, and created serious medical, social and economic problems in China. As Cheng Hanzhang, a Chinese official, described it, opium was “a poison that foreigners do not use themselves but still sell to China, harming our people, consuming our wealth to the tune of millions of taels per year, all secretly in exchange for silver that will leave and never come back.”

All of this and other issues led to what became known as the Opium War, which last from 1839 until 1842 and ended in defeat for China. It marked the end of long period in which China was powerful, prosperous and envied around the world, and the beginning of what China has called its “Century of Humiliation” in which European, American and later Japanese governments would seize Chinese territory, meddle in Chinese politics and dictate Chinese trading policies. The Opium War and what came after continues to color Chinese perceptions of the rest of the world; according to one historian, “No event casts a longer shadow over China’s modern history than the Opium War.”

That British merchants did not see anything wrong with their actions is reflected in this bowl. It was part of a large service meant for elegant dinner parties, and may have been used on board Red Rover, or by William Jardine or James Matheson in their homes in Macao, Hong Kong (which the British got in 1841 as part of the settlement of the Opium War), or Scotland. The name of their fastest and most famous ship, emblazoned on a garter (a heraldic device that had connotations of the exalted Order of the Garter), would have been an obvious reminder of the source of their wealth and influence.

The Red Rover salad bowl is on display at the Reeves Center on the Washington and Lee campus. Read more about the Reeves Collection here.

This bowl, emblazoned with the name of the ship Red Rover, is intimately connected to opium smuggling and the first Opium War.

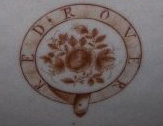

This bowl, emblazoned with the name of the ship Red Rover, is intimately connected to opium smuggling and the first Opium War. Detail of Red Rover medallion

Detail of Red Rover medallion

You must be logged in to post a comment.