Pulitzer-Winning Team Includes Two W&L Alumni Michael Hudson '85 and Scott Bronstein '93 both worked on the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers investigation, which relied on the collaboration of some 400 journalists around the world.

In 2015, an anonymous source leaked more than 11 million financial and legal records pertaining to secret offshore companies. This leak of what would eventually be known as the “Panama Papers” launched a massive reporting project that involved some 400 journalists from around the world, including two Washington and Lee University alumni. Michael Hudson ’85 is a senior editor at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists; he reported on the project and was one of the main editors. Scott Bronstein ’93 is editor of the English language section of La Prensa newspaper in Panama; he and his wife, Rita Vasquez, an attorney who also works for La Prensa, did reporting on the project, helped other reporters understand offshore companies and assisted with contacts in Panama.

In April 2017, the Panama Papers investigation received the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. The award is shared by ICIJ, McClatchy, the Miami Herald, the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners.

Hudson and Bronstein took time to fill us in on their involvement in the project and their memories of being journalism students at W&L.

“Journalists aren’t necessarily known for teamwork and patience. This project showed what can happen when we treat each other as allies instead of competitors – and are willing to work for a year or more to dig into stories that are hard to unravel.”

— Mike Hudson ’85

What is ICIJ and how did it become involved in this story?

ICIJ is a nonprofit news organization. Its funding comes from many of the same kinds of foundations, such as Ford and the Pew Charitable Trusts, that support National Public Radio. We’re headquartered in Washington, D.C., but much of our staff of 15 is spread out around the globe – we have team members in Australia, Costa Rica, Spain, Paris and New York (that’s me, in Flatbush, Brooklyn, a few blocks from where the Dodgers used to play).

We operate on the principle that many stories are too big, too complex and too global for a lone-wolf reporter or single news organization to tackle. Over the past five years we’ve partnered with dozens of news organizations and hundreds of journalists around the world to investigate offshore-fueled money laundering and tax evasion. Each project was sparked by a leaked trove of files documenting who’s behind shell companies and secret bank accounts. The Panama Papers investigation began after one of our longtime media partners, German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung, received a new leak of unprecedented size – 11.5 million digital files from a Panama law firm that specializes in setting up offshore companies for clients who want to remain in the shadows. Instead of hoarding the documents for themselves, our German partners shared them with ICIJ, allowing us to pull together a cross-border partnership and join forces with SZ, McClatchy, the Miami Herald and more than 100 other news organizations to investigate the explosive documents.

In all, more than 400 journalists worked on the project.

Working with just one other journalist on a project can be a challenge. What was it like having hundreds of journalists working on the same project?

Difficult and invigorating. Working with so many smart, relentless reporters from around the world was wonderful. They knew lots of stuff I didn’t know and, occasionally, I knew stuff that they didn’t know. All of us were able to pool information and resources and come up with stories that were stronger and deeper than if we’d worked alone.

Journalists aren’t necessarily known for teamwork and patience. This project showed what can happen when we treat each other as allies instead of competitors – and are willing to work for a year or more to dig into stories that are hard to unravel.

To be part of the collaboration, you had to agree to (1) share your research and reporting with everyone else, and (2) wait to publish or broadcast at a common go-date. No. 2 made No. 1 easier to live with – knowing you weren’t going to get scooped made it easier to think about sharing information with journalists from other news outfits. We used password-secured, online platforms to swap documents, questions and interview notes.

What was the most exciting moment for you in the process of reporting this story?

The biggest waves of excitement came in early April 2016, after ICIJ and all of our partners began releasing our first stories. The response around the world was amazing. There was a firestorm of media, political and grassroots reaction. #PanamaPapers quickly became the No. 1 trending topic on Twitter. Citizens hit the streets in protest. They threw rocks in Pakistan and cultured yogurt in Iceland. Iceland’s prime minister and other high-profile figures were forced to resign. American network news, comedy shows – and even the daily newspaper cartoon Doonesbury – were compelled to weigh in on the Panama Papers. Dozens of countries have passed new laws toughening anti-money-laundering standards. More than 150 inquiries, audits and investigations have been launched in roughly 80 countries. The reverberations are still being felt in places like Pakistan and Uruguay, more than a year later.

Can you describe the vibe in the room when you and your colleagues learned that you had won a Pulitzer? How did you all celebrate?

We had about 15 people in our cramped headquarters in D.C., along with team members from around the world on video chat. We watched the Pulitzer board’s livestream of the announcement. When we heard that the Panama Papers investigations had been selected as the winner of the Pulitzer for Explanatory Reporting, there was some cheering, hugging and high-fiving. We popped a couple of bottles of champagne. Maybe because we work so hard, we don’t really remember how to party, in the old Front Page newsroom/”Mad Men”-style. We ended up taking lots of phone calls, answering emails, putting out a story about the honor, etc. We went out to dinner together and then the next day, we were talking about what we needed to do on our next investigation.

Let’s look back to your time as a journalism student at W&L:

I wasn’t a serious student in high school. I was mostly interested in playing basketball and drinking beer. While I was at Ferrum College and University of Richmond, I was a bit more serious, and I did reporting internships at the Richmond Times-Dispatch and The Roanoke Times. All that helped prepare me for the challenges I faced when I transferred for my junior year at W&L.

I had some great teachers in sociology and economics, but I spent most of my time either in Reid Hall or over on Main Street at The Roanoke Times’ now-defunct Shenandoah Bureau. Throw in basketball practices and games, and I was busy most waking moments. I never worked for the Ring-tum Phi, but I stuck my nose in its business by writing letters to the editor questioning the paper’s editorial decisions and calling out behind-the-scene intrigues regarding control of its top management positions.

All in all, I learned a lot about journalism, in a lot of different ways.

Which professors made a lasting impact on you, and why?

Professor John Jennings taught me the intricacies of media law – always vital knowledge if you’re trying to do investigative reporting. Professor Ham Smith helped me get over my timidity about asking tough questions and my nonchalance about meeting deadlines; I feared his wrath and valued his words about the responsibilities and burdens of being a reporter.

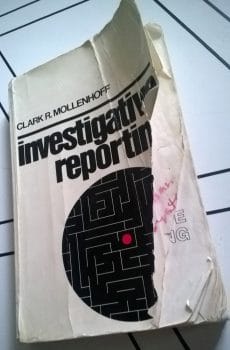

The late Professor Clark Mollenhoff, who won a Pulitzer in the 1950s for his investigations of Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters, introduced me to the work of the muckrakers of the early 20th century, showing how their techniques could be adapted for modern times. He taught me that good journalism wasn’t about hierarchies and connections, it was about hard work. You don’t have to be part of the media in-crowd to do good work. You just have to be meticulous and dogged. A reporter with a “controlled sense of outrage at injustice, unfairness or corruption,” he said, could succeed as an investigative reporter through hard work and the application of “systematic and logical research techniques.”

I still crack open his book, “Investigative Reporting: From Courthouse to White House,” whenever I feel stuck on an investigation and need inspiration. Its pages are crisscrossed with underlines and notes, and the paperback cover has begun to flake away from overuse.

Can you recall any particular lessons that you have carried with you in your career to this day?

Never be satisfied. Always ask five more questions in an interview than you think you need to ask. Always make 10 more phone calls than you think you need to make. Never hold back accurate, relevant facts from a story because you’re worried about angering your sources. If they’re principled and reliable sources – rather than spin doctors – they’ll live with it, even if they don’t like it.

Despite major concerns about fake news and decreased trust and respect in mainstream media, journalists seem busier than ever since the new administration took the White House. Is it possible that today’s political climate is actually helping journalism?

I think Trump and his aides have given the news media a huge gift.

By making it clear that it considers anything other than deferential coverage to be fake news, the Trump administration has freed many journalists from the usual tendency to suck up to powerful figures in the hope that they can cultivate high-level officials as sources of inside color. Instead, reporters can just do their jobs – tracking down sources at all levels of government, squinting over court records and other documents, and generally digging deeper than the standard-operating methods of access-driven journalism typically allow.

While print newspapers continue to downsize and struggle, ICIJ shows that there is a way to keep digging deep on big, investigative pieces. What can current journalism students take away from this? What about everyday news consumers?

The media world has been fraught with struggle and hope for as long as the news business has been a business. I worry about the loss of local reporters around the country, but I’m mostly optimistic, especially about national and international coverage. There are plenty of good things going on in journalism and hundreds of new jobs with interesting new angles of vision – thanks to nonprofit funding models, the rise of Big Data and technologies that allow stories to be told in new ways and spread farther than ever before.

If you know any W&L alumni who would be great profile subjects, tell us about them! Nominate them for a web profile.

Scott Bronstein '93 Reports from Panama

How did a Pennsylvania native end up living and working in Panama?

In 2002, I took a job for the BVI Beacon in the British Virgin Islands. I had been working for a daily newspaper, and I saw it as an opportunity to try something different.

While there, I started writing stories about the offshore financial industry, as the BVI is one of the largest jurisdictions in the world. I also met my wife, Rita Vasquez, who was working for a Panama law firm that had an office in the BVI. We got along fairly well, and in 2007, we decided to move to Panama where she would further her law career.

The move was somewhat risky as I didn’t have any good job prospects. But at that time, Panama’s economy was growing, and it was becoming a top location for ex-pats, so I figured there would be opportunities for me to find something to do.

As it happened, a few months after we moved, a local newspaper decided to start an English language section, and I was hired to run it. At the same time, Rita was offered a management job at the newspaper, so she decided to give up her legal career to become a journalist. Personally, though, I think she couldn’t resist the opportunity to boss me around at both the house and the office.

As a W&L student, were there particular classes or professors that made a lasting impact on you?

In all honesty, I was a terrible student. I didn’t work very hard and pretty much spent four years reluctantly dragging myself to classes. Looking back on it, I probably wasn’t ready to go to college right after high school.

But that doesn’t mean I wasn’t paying attention. Professor Brian Richardson was a brand-new professor when I was there, and I worked with him on a paper my senior year that involved combining elements of philosophy with journalism. It was somewhat ambitious, and working with someone who was battle-tested in the industry helped me out a lot.

I also took a course with Professor Ham Smith during the spring semester of my senior year in which we spent six weeks working on one article. I did a long-form feature story on a local NASCAR driver that turned out pretty well. At my first job a few months later, I spent a few weeks working on a story about a high school basketball player whose chances at a scholarship were ruined when he was shot while walking near a playground where a drug deal was taking place.

I don’t think that story would have turned out as well as it did without my experience of working closely with my professors at Washington and Lee.

Do you recall your initial reaction/impressions when you first heard about the Panama Papers leak?

My wife was invited to go to Germany for a meeting about the project, which was top secret. She couldn’t even tell me why she was going. So the first time I heard about the project was when we were driving home from the airport. When she told me about it, I didn’t think it was going to be a big deal. This was because, while I didn’t know that much about the firm involved, I knew the kinds of things she had done while working as a lawyer. And it was pretty boring stuff. Her clients were mainly people setting up trusts for their kids and companies that needed help with issues like currency conversions.

But that all changed when I started looking at the files, and I realized that Mossack Fonseca was nothing like her firm. In all honesty, if Rita’s files were made public from her days as a lawyer, you couldn’t pay newspapers to run stories about them. But when I saw the names of the people in the Mossack Finseca files, I knew right away that it was going to have a worldwide impact.

Describe you and your wife’s involvement in the reporting of this project.

There were a number of prominent politicians from Panama in the files, including a former president, so I wrote those stories. I also wrote a major story about a native of Guatemala who was living in the United States and who appeared to be using a venture capital firm to launder money and evade taxes. That story wasn’t picked up by any of the U.S. partners, but the New York Times covered it extensively in one of its stories.

In addition to the reporting, my wife was getting several questions a day from partners in the project about information in the files that they didn’t understand. She had a hard time keeping up with all these queries, so I started helping her answer them. We also helped provide information about the firm, the history of the offshore industry and Panama and the BVI.

We also hosted the partners who came to Panama, including seven television stations. We set them up with interviews with people who worked in the industry and helped them with the stories that they were working on.

What we weren’t allowed to do was to appear on camera ourselves, as there was a concern about our safety. I didn’t agree with this decision, but it was probably the right choice. It’s one of the reasons that our involvement in the project was somewhat a secret.

What were the best and worst aspects of working on this project?

The best aspect was working with so many incredibly talented journalists from around the world. It’s hard to put into words, but for me, this was basically like getting to tag along with Woodward and Bernstein while they were investigating Watergate. As a journalist, you dream about being involved in something like this.

The worst part was losing a lot of close friends. Rita and I knew a lot of people who worked at the firm. For example, its compliance officer, who will never get another job and who could end up in prison, graduated from high school with Rita. So she has been blamed by a lot of people for ruining that person’s life, even if it wasn’t really her fault.

How’d it feel when you heard about the Pulitzer?

When the award was announced, I wasn’t that excited initially because I figured that only the U.S. media partners would get to take credit for it. Then I started getting text messages from people congratulating me, and I realized that I had to figure out what was going on, because I didn’t want to take credit for something I didn’t win. A short time later the ICIJ sent out a message making it clear that everyone who worked on the project got to share in the award, so that was my answer.

What has this experience, and the experience of being a career journalist, taught you about the profession that you would like to pass along to current journalism students?

I think the biggest lesson that I have learned is that the future of journalism may not be one that is competitive, but one that is collaborative. As globalization becomes a greater reality, the media has to ask itself if it is capable of adequately covering stories that have aspects to them that impact several different parts of the world.

During the Panama Papers, I worked on stories with reporters from Brazil, Costa Rica, the U.S., the U.K. and Germany. For one story, I had to track a $500 million gold transaction made by a Colombian citizen working for a German company that was processed by a brokerage house in Panama through a trust in a British Overseas Territory. Individually, I don’t think any newspaper or media house would have the resources to have properly investigated that story on its own. But through a collaborative effort, it was reported thoroughly in several different countries, expanding its impact.

I think that the media in general can learn something from the Panama Papers, which is that to adequately cover global stories in times of shrinking resources, it may be necessary to create partnerships and to work together. And if you look at an organization like the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, that is exactly the kind of model they are promoting.

Michael Hudson ’85 served as a senior editor on the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers project.

Michael Hudson ’85 served as a senior editor on the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers project. Hudson joined a panel discussing “Journalism in the Age of Trump” on the W&L campus in March 2017.

Hudson joined a panel discussing “Journalism in the Age of Trump” on the W&L campus in March 2017. Mike Hudson’s well-used copy of Professor Clark Mollenhoff’s book.

Mike Hudson’s well-used copy of Professor Clark Mollenhoff’s book. Scott Bronstein (right) with his wife, Rita Vasquez.

Scott Bronstein (right) with his wife, Rita Vasquez.

You must be logged in to post a comment.