Squirreled Away The 13-lined ground squirrels currently residing in the Science Center for associate professor of biology Jessica LaPrice’s research have inspired a cross-campus collaboration that showcases W&L’s emphasis on hands-on learning.

Ground squirrels hibernating under the comfort of hand-made quilts might conjure images of Beatrix Potter characters come to life, but for Jessica LaPrice, associate professor of biology at Washington and Lee University, these small creatures are more than cute — they’re an integral part of her research on the biological processes that occur during hibernation cycles, as well as a unique opportunity to showcase the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of a W&L education.

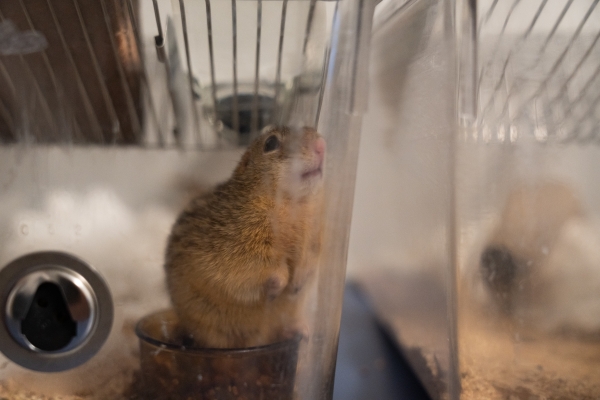

W&L’s Science Center is currently home to a small colony of 13-lined ground squirrels that LaPrice transported last summer from Iowa to Virginia in a truly one-of-a-kind road trip. The juvenile squirrels emerged from their first hibernation in March and are now spending the summer preparing for their return to hibernation in the fall. This seasonal lifestyle is what makes the squirrels such an intriguing research subject, and LaPrice’s lab studies the physiology of the squirrels as they transition in and out of hibernation.

Ground squirrels are active in the summer, like the non-hibernating tree squirrels we’re most familiar with, and they do as much as possible to gain weight before going into hibernation. Then, LaPrice explains, a switch flips at a certain point, and their body temperature drops to match the outside temperature. They burrow underground, where their body temperature adapts to the temperature of the soil. Because the squirrels’ body temperature and metabolic rate drop so significantly, they are not burning nearly as much energy, and their bodies begin burning the fat they stored during the summer and burn through it over the course of the winter.

“What happens when the squirrels are in hibernation is basically the cessation of most normal biological processes,” LaPrice said. “Everything is just really slow, as if they’re in suspended animation. In a way, they act ‘warm-blooded’ during the summer and ‘cold-blooded’ in the winter. Then, the switch flips back in the spring, and they go from hibernation to resuming their summertime active lifestyle from just one day to the next.”

The ground squirrels’ weight might drop from 350 grams to 100 grams over the course of hibernation, and their body temperature drops to match the temperature of the ground, which is usually 40 degrees Fahrenheit. The squirrels’ heartbeat also slows to two or three times per minute, from a normal rate of 300 beats per minute, and they breathe only once every two to three minutes.

As soon as the squirrels emerge from hibernation, they begin reproducing and eating to prepare for the next hibernation cycle. The immediacy with which this shift happens is unusual for mammals, which typically can’t go through an estrus cycle and reproduce with diminished fat reserves. Once they mate, the male squirrels will begin gaining weight and go into hibernation in July, followed by the females in August, once they have nursed their offspring and stored fat for themselves. The juveniles won’t hibernate until October or November, spending those months gaining as much weight as they possibly can.

Hands-On Learning

Kylee Cross ’27 and Brian Kim ’26 spent this past Winter Term working as student researchers with LaPrice to track these transitions in and out of hibernation, particularly that “spring switch” when the squirrels emerge from hibernation and immediately resume an active lifestyle. The team first used thermal cameras to observe the squirrels while they were hibernating inside the lab and moved the squirrels to their individual cages when they woke up. Cross and Kim then monitored the squirrels every day, conducting feedings and routine blood draws to test hormone levels, metabolic rates and oxygen levels. Tracking these indicators gives LaPrice and her team a better idea of why the squirrels can quickly bounce back from the energy deficit they experience in hibernation and resume an active lifestyle.

Kim was inspired to work on more animal studies after conducting research with Nadia Ayoub, professor of biology, on the circadian rhythms of spiders, and he found this experience translated well to studying the hibernation patterns of the ground squirrels. He was pleasantly surprised by how hands-on he was able to be throughout the study, including being able to anesthetize the squirrels for their blood draws. A biology major on a pre-veterinary track, Kim had experience shadowing veterinarians at a clinic, but LaPrice’s lab offered unique opportunities to handle the animals he was caring for and gain valuable experience for his future career.

“This was my first time handling animals in a research setting, having only handled small animals like dogs and cats at the veterinary clinic,” Kim said. “The level of involvement, including helping with the anesthesia, was totally unexpected, but relevant to veterinary school and allowed me to get more animal experience.”

Like Kim, Cross was not expecting the chance to be so involved in the research and is grateful for W&L’s emphasis on a well-rounded liberal arts education that allowed her a hands-on research experience along with a variety of opportunities across campus, including Army ROTC. Working with the ground squirrels was also Cross’ first clinical experience, and as an animal-lover who plans to attend medical school, she appreciated the opportunity to work closely with the squirrels (she could eventually tell them apart based on their different personalities!) and become more comfortable in a lab setting.

Beginning in June, LaPrice was joined by two students in the Summer Research Scholars program, Whitney Obialor ’28 and Christina Ziccardi ’27, and Lia Rodriguez Moreno ’29, who is participating in the Advanced Immersion and Mentoring (AIM) Summer Scholars Program. Obialor, Ziccardi and Moreno are continuing to build an in-depth profile of how this species of ground squirrel transitions between life stages during their active season. The team will study how long the squirrels stay in their breeding season and how they transition to the summer fattening stage to prepare for the coming winter’s hibernation. The scale of the project will also expand over the next couple of years, with the current squirrels reproducing and LaPrice and her students traveling back to Iowa to gather more squirrels for the colony.

Collaboration Across Campus

To best study the squirrels’ hibernation cycles, LaPrice had to mimic the conditions of an underground burrow in a lab setting, creating a dark, quiet and cold environment where the squirrels can naturally transition in and out of hibernation.

The solution was to create a chamber — picture a walk-in refrigerator — that can mimic the seasonal temperature changes and stay cold all winter. The squirrels, each in their individual cages, can then move through their natural cycles, offering a singular opportunity for LaPrice and the students to study their hibernation patterns. However, this man-made solution also created a few man-made complications. The chambers make a lot of noise, and every time the door is opened to check on the squirrels, they are exposed to light and more sound, potentially disrupting their hibernation.

“Because the animals are seasonal, we have to keep and use the same squirrels all year-round for this experiment,” said LaPrice. “The fewer times they wake up during hibernation because of disturbances, the more likely they are to be in good body condition, to be healthy and to be as close to what they would be in a natural setting as they can possibly be in the lab. What we want is a healthy, happy animal that is as least stressed as possible and closer to how they normally would be in the field.”

LaPrice mentioned this dilemma in passing to Chawne Kimber, then dean of the College, who suggested squirrel quilts to drape over the cages and keep out sound and light. A quilter herself, Kimber knew to direct LaPrice to Ady Dewey, the Reynolds Visiting Assistant Professor of Strategic Communication, who was teaching Fast Fashion during Winter Term 2025 and had collaborated with Kimber in the past on upcycling projects.

This partnership was quintessentially liberal arts, with Dewey’s class receiving a hands-on education about upcycling and the textile industry while supporting the scientific research of LaPrice and her students. Julie Knudson, before retiring from her position as ITS technology adoption and training coordinator, also joined the project to guide Dewey’s students in creating the quilts with the sewing machines housed in W&L’s IQ Center, an interdisciplinary and collaborative space designed to foster scientific curiosity, literacy and creativity.

“The project was a natural intersection,” said Dewey. “Jessica had the need, I provided the labor, and Julie provided the instruction.”

The Fast Fashion class is designed to be interdisciplinary and examines issues of overconsumption and sustainability. Dewey, who was teaching the class for the third time, welcomed the opportunity to take a new approach to the class and provide her students with hands-on textile experience.

Working with quilts, quilted placemats and table runners that Dewey and Knudson bought from thrift stores, the students created a pattern to fit over the squirrel cages and began crafting the covers on the sewing machines in the IQ Center. In addition to learning the tangible skills of sewing, which most of the students had not done before, the process introduced them to the benefits of upcycling and encouraged them to consider how clothes are made and the life cycle of a piece of fabric.

“This project was a chance to look at how we can interrupt the cycle of purchasing-to-landfill by upcycling,” said Dewey. “It’s looking at the textile industry from another angle and giving the students a sense of what I think is one of the reasons we have become an over-consumption society, that we’ve lost the thread of where our clothes come from — who’s made them and how they have been made. Working on the quilts can open up opportunities for students to look at something they’ve taken for granted, like the clothes they chose to wear that morning, and think about it differently.”

Knudson agrees that having the students make the quilts themselves helps them put a lot of textile creation and the fashion industry into perspective. She also believes that it’s important for the students to learn basic sewing skills, as the textile arts are not only a creative pursuit (and a personal passion of Knudson’s) but also encourage W&L students to engage with the IQ Center and provide an accessible entry to STEM fields for students of all backgrounds.

“My favorite part of working with students in the makerspace is to see that ‘aha!’ moment when they have made something and have that sense of pride in what they’ve created,” Knudson said. “So often in education, you can’t immediately see the results of what you’re learning — it’s intangible. But right in the makerspace, you have tangible results.”

The quilts that Dewey’s students made will be used when the squirrels return to hibernation this fall in a newly renovated chamber within the Science Center, a project supported by Drew Kepley, university architect and director of planning, design and construction; Kevin Beanland, associate dean of the College for administration; and Kjellstrom + Lee Construction. This larger chamber will better accommodate the environmental needs of the hibernating squirrels, as well as the growing size of the colony.

Throughout the project, LaPrice has appreciated the amount of collaboration and support she has found across campus and is grateful for the work her colleagues have contributed on behalf of the squirrels.

“This is a really liberal arts moment of bringing together so many different interests while doing something for the health and well-being of the animals we’re working with,” LaPrice said. “And the more we can provide students with the clear, useful skills and interdisciplinary activities that we can as part of this liberal arts experience, the better they’re going to be as citizens, as humans, as scientists, or anything they end up doing.”

Why It Matters

Studying the physiology of hibernation is important because animals that hibernate tend to live longer than animals that don’t hibernate. This is in part because prey animals are less likely to be eaten when burrowed underground several months out of the year, but also because they can repair the damage that happens to their body over hibernation.

Specifically, the telomeres that protect the ends of chromosomes become shorter with age, leading to increased exposure of the chromosomes and potential damage, but during hibernation, these telomeres get longer. Learning how to better protect or even restore telomeres can help us better understand the physiology of aging in humans and how to treat complications of aging.

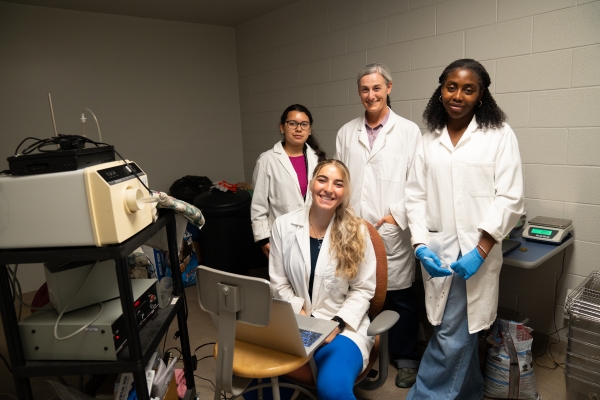

Professor Jessica LaPrice with Summer Research Scholars Whitney Obialor ’28 and Christina Ziccardi ’27, and AIM Scholar Lia Rodriguez Moreno ’29.

Professor Jessica LaPrice with Summer Research Scholars Whitney Obialor ’28 and Christina Ziccardi ’27, and AIM Scholar Lia Rodriguez Moreno ’29. The seasonal lifestyle of 13-lined ground squirrels makes them an intriguing research subject.

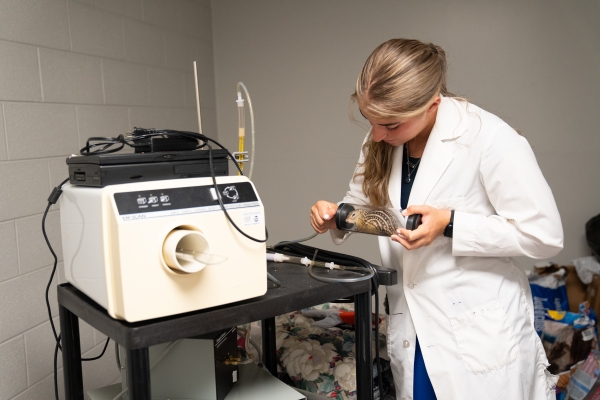

The seasonal lifestyle of 13-lined ground squirrels makes them an intriguing research subject. A team of student researchers are studying the squirrels’ physiology as they transition in and out of hibernation.

A team of student researchers are studying the squirrels’ physiology as they transition in and out of hibernation. The individual cages pictured here will be covered by the student-made quilts when the squirrels go into hibernation this fall.

The individual cages pictured here will be covered by the student-made quilts when the squirrels go into hibernation this fall. The squirrels will return to hibernation in a newly renovated chamber within the Science Center. The larger chamber will better accommodate the environmental needs of the hibernating squirrels, as well as the growing size of the colony.

The squirrels will return to hibernation in a newly renovated chamber within the Science Center. The larger chamber will better accommodate the environmental needs of the hibernating squirrels, as well as the growing size of the colony.

You must be logged in to post a comment.