Mapping the Past As part of a community-based learning course in collaboration with Rockbridge Regional Tourism and the Rockbridge Historical Society, Washington and Lee University students researched and mapped Black-owned businesses that thrived in Lexington during the Jim Crow era.

“… a lot of people who do know Lexington are not aware of the Black businesses that were once here. The fact that these businesses thrived should be celebrated. Their histories are important.”

~ Professor Sascha Goluboff

Students in a community-based learning course at Washington and Lee have helped to highlight the hidden histories of Lexington’s Black-owned businesses on a digital map that expands on ongoing efforts by the Rockbridge Historical Society.

The course, Unheard Voices of Black Lexington, was taught this Winter Term by anthropology professor Sascha Goluboff, director of the Office of Community-Based Learning (CBL). It focused on Black businesses that thrived in Lexington during the Jim Crow era, and included historical research and guest speakers who offered accounts of growing up in the community.

The digital map expands on a model that Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society, developed several years ago when he created a walking tour of Diamond Hill and the Green Hill community as the outgrowth of a fourth-grade Virginia Studies project. In 2019, he then worked with a class of James Madison University public history and computer science students to further develop a prototype of an interactive map that helps visualize changes in the neighborhood from the late-19th to the mid-20th centuries.

“Sometimes with individual student projects, it can be harder to get follow up,” said Wilson, who was also a guest speaker in the W&L class. “A professor steering a project provides a real anchor, and Sascha’s own expertise in local histories clearly paved the way for authentic student inquiry. This map will have value in the Visitor Center but will also allow for greater storytelling as a web-based map.”

Working with the Historical Society and Rockbridge Regional Tourism, students began by investigating the histories of such erstwhile Lexington businesses as the Rose Inn, the Walker & Wood Brothers Sanitary Meat Market and Joe Wood’s Subway Barber Shop. The students’ narratives now populate the digital map, which the Visitor Center can use to help increase awareness of Black residents’ contributions to Lexington.

“I’m excited to have this opportunity both to learn more myself and then to share this information with our visitors,” said Jean Clark, director of tourism for Lexington and the Rockbridge area. “This project has been an excellent way to connect students with the community and vice versa.”

Goluboff said that CBL courses create opportunities for participants to reflect on their experiences in the community. In Unheard Voices, she wanted students to dig as deep into themselves as they were digging into the histories they were uncovering.

“Most students don’t know Lexington,” she said. “But a lot of people who do know Lexington are not aware of the Black businesses that were once here. The fact that these businesses thrived should be celebrated. Their histories are important.”

Many of these businesses were located on North Main Street. Among the most prominent was Walker & Woods Brothers Sanitary Meat Market, which was located in the white-columned building that has since been the site of several restaurants, most recently Macado’s. Harry Lee Walker purchased the building in 1911 and established the market. With the help of his son-in-law Clarence Wood, the market became renowned for its smoke-cured Virginia hams. The business was also the principal supplier of meats to VMI.

Three Lexington businesses, Washington Café, Rose Inn and Franklin Tourist Home, were featured in The Negro-Motorist Green Book, the segregation-era compilation of businesses that would accept and were safe for Black customers throughout the U.S. Published between 1936 and 1967, the Green Book was featured in the somewhat controversial movie of the same name, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2018.

The Rose Inn property was purchased by VMI in 1983 and was torn down in 2018 to make way for VMI’s Corps Physical Training Facility. The Franklin Tourist Home, run out of the home of Zack and Arleana Franklin, is still standing on Tucker Street in the Diamond Hill neighborhood. It was a common stop for travelers, including Black musicians who came to Lexington to perform at W&L functions and chauffeurs who dropped their white patrons off at the R.E. Lee Hotel.

As she was mapping out the course, Goluboff and several of the class’s peer mentors uncovered deeds and documents to provide context to the businesses. They discovered that the Subway Barber Shop had once operated downstairs in the building known as the Jacob Ruff House, which is on the National Registry of Historic Houses and has been a staple on historic tours.

“In our research, we found mentions of a barber shop that was supposedly across from the Woods Brothers Market,” said Goluboff. “Once we did a deed search on the Ruff House, we discovered that Joe Wood and his brother Clarence became owners of the house in 1928 as the result of a court case and opened the barber shop on the first floor. That part of the building’s history had been erased, and this is what we were trying to bring back to life.”

Other businesses highlighted on the students’ map include Clark’s Pool Room, Dock’s Tea Room and the offices of two Black physicians, Dr. John H. Gilmore and Dr. Alfred W. Pleasants. The map also features the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, Lodge 2461, a Black fraternal organization, the members of which pooled their resources to buy several buildings to house Black businesses.

“I have always thought that the past gives us an insight into how things operate in the present,” said Christian Basnight, a first-year student from Virginia Beach. “Looking into documents like the 1930 and 1940 censuses and into the old photographs made a profound impact because it showed me these were actual people with complete life stories.”

Even as they were building their narratives, the students were asking questions of themselves and of each other, and several students referred to the experiences as having helped pierce that infamous Washington and Lee bubble.

“I do think W&L is very much a bubble,” said Elspeth Suber ’21, a sociology major from Tallahassee, Florida. “Students get into their own social circles, and you have to be intentional about leaving that bubble. The CBL program with its course work has been a great way to disrupt this pattern which, in my view, has been going on for way too long.”

Jhade Jordan ’21 acknowledged that W&L students may have interactions with the community as students, perhaps as volunteers or by attending church services. But in her view, the class took the interaction to a different level.

“Learning more about the history of the community did pop the bubble a bit,” she said. “But I also think there are bubbles within bubbles at the university. There are many communities inside W&L, and I’ve been able to interact with a lot of people here that I’ve not interacted with in the last four years.”

Those interactions were often intense. Goluboff engaged four peer mentors, each of whom was a student of color and all of whom led the small group discussions that followed her lectures. “Students do a lot of critical reflecting in the class,” she said, “and I thought peer mentors could help them reflect on what it’s like, for example, to be a Black student at W&L and in Lexington.”

Although COVID-19 pushed the class onto Zoom, Goluboff credited the peer mentors with successfully guiding the conversations in that format.

Tanajia Moye-Green, a sophomore from Mulberry, Florida, was one of the peer mentors. She spent part of the summer of 2020 assisting Goluboff on research for the course, which included sifting through documents in Special Collections and at the Rockbridge Court House as well as having conversations with community members.

Moye-Green had some notions about the history she would be uncovering but said it was still disheartening to realize how segregated Lexington was.

“The Confederacy has been the primary focus of the history of Lexington, and the Black community has been mostly side notes,” she said. “I was interested in learning for myself what life looked like for Black people and how it’s changed. I also wanted to be part of creating something that will present this information to others.”

Moye-Green said leading the discussions was emotionally exhausting as she related personal stories of confronting racism growing up and drew connections to what they were learning about Lexington in the Jim Crow era. The process, she said, worked because the students were willing to be open and honest in their conversations.

“It’s one thing to be at arm’s length from the story and another to hear experiences of someone you know,” she said. “You are occupying the same space but having two very different experiences.”

Jenny Lerner ’24 grew up in Massachusetts and credits Moye-Green and the other peer mentors for lending their very personal insights. She said that the hour and a half always flew by. “Everyone is inclusive in the discussions,” she said. “We all say what we want to say. There are lots of different viewpoints, and I’ve gained so much valuable insight into myself.”

Lerner opted for a community-based learning class in only her second semester because she had hoped to get hands-on experience that would take her out of her comfort zone. COVID-19 put a stop to the hands-on part, but she has definitely been challenged on many levels.

“It had never occurred to me before I got to W&L how racially divided this area was,” she said. “I’ve realized how important it is to acknowledge the privilege I have as a white person. A lot of people walk around wearing a blindfold. It’s easier to ignore things and say I’ll deal with it later and not acknowledge the privilege race can give somebody. This class forced me to remove the blindfold and talk about things that are uncomfortable.”

As opposed to Lerner, Suber was quite familiar with Lexington’s history. Her family has a long connection with the area. She’s even related, by marriage, to Stonewall Jackson. Plus, her father, Jesse, is a 1980 W&L alumnus.

“I was aware of what the narrative of these Black businesses would be, but it was still sobering,” Suber said. “My group examined the work of one of the Black physicians, Dr. Gilmore. But rather than focus on the negatives, like the fact that he wasn’t allowed to see patients at Stonewall Hospital because of the segregation there, I really cared about celebrating how he provided health care to Lexington residents, both Black and white, who were otherwise denied health care.”

Like Lerner, Suber believes the peer mentors provided important context and said that “even with Zoom, this has been one of the most beneficial and engaging classes that I’ve ever had.”

The interaction with the community included guest speakers, such as pastors and Lexington natives, who offered important perspectives and had clear impact on the students. “The community members gave us a lot of first-hand information,” said Suber. “Each speaker selected a reading for us, and we wrote them a response letter to reflect on our discussions. It was an important element of the class.”

Wilson echoed the value of that exchange, saying that “those student letters were not only a meaningful signal of their own current historical curiosities and growth, but also highlighted some new areas our institutional work can build on and emphasize in the future.”

The map is a tangible product that will last well beyond the class, but Goluboff hopes other lessons may last longer.

“I am hoping the students will get a better sense of their place in the world and what they can do to make a positive change,” said Goluboff. “Since change is incremental, I hope the class will also show them the change we do make may be small but over time can lead to big change. Most of the change-makers aren’t the big ones out there we know about; they’re the everyday things we do.”

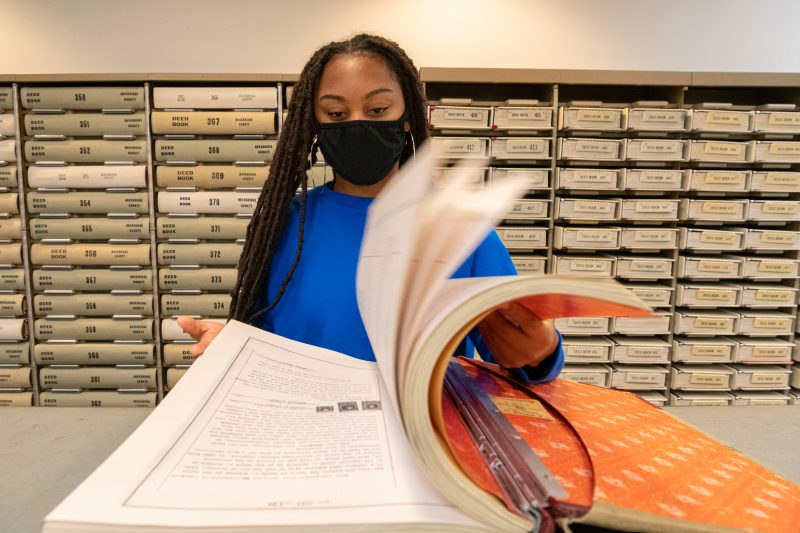

Tanajia Moye-Green ’23 and Kamryn Godsey ‘23 work with Director of Community-Based Learning Sascha Goluboff to search property records in the Rockbridge County Courthouse.

Tanajia Moye-Green ’23 and Kamryn Godsey ‘23 work with Director of Community-Based Learning Sascha Goluboff to search property records in the Rockbridge County Courthouse. Professor Sascha Goluboff, Tanajia Moye-Green ’23, Kamryn Godsey ’23, Assistant Director of Special Collections Seth McCormick-Goodhart and Lexington resident Ely Spencer listen as Lexington native Francis Watts talks about Black Lexington during a walking tour of the city.

Professor Sascha Goluboff, Tanajia Moye-Green ’23, Kamryn Godsey ’23, Assistant Director of Special Collections Seth McCormick-Goodhart and Lexington resident Ely Spencer listen as Lexington native Francis Watts talks about Black Lexington during a walking tour of the city. Elspeth Suber ’21 and Phil Kinoti ’21, both students in Unheard Voices of Black Lexington, participate in a scavenger hunt that required them to find the site of historic Black-owned businesses in Lexington today.

Elspeth Suber ’21 and Phil Kinoti ’21, both students in Unheard Voices of Black Lexington, participate in a scavenger hunt that required them to find the site of historic Black-owned businesses in Lexington today. Jade Krol ’22 and Phil Kinoti ’21 participate in a scavenger hunt to find the site of former Black-owned Lexington businesses as part of CBL 100.

Jade Krol ’22 and Phil Kinoti ’21 participate in a scavenger hunt to find the site of former Black-owned Lexington businesses as part of CBL 100. Kam Godsey ’23 searches property records for black-owned businesses in the Rockbridge County Courthouse as part of a community-based learning project for a class that will be taught during Winter Term.

Kam Godsey ’23 searches property records for black-owned businesses in the Rockbridge County Courthouse as part of a community-based learning project for a class that will be taught during Winter Term.

You must be logged in to post a comment.