‘There’s Nothing Like Art’ A generous donation of art last year from Rick Kramer '69 includes three works by Sam Gilliam, one of the most significant living artists of our time.

Mid-December seems a lifetime ago. That’s when I installed the painting “Chinese” by African American artist Sam Gilliam, a recent gift from Richard E. Kramer ’69, in Wilson Hall. Gilliam, whose work is both experimental and experiential, is one of the most significant living artists of our time.

The installation was intended to support a Winter Term course on African American Art and to be a resource for future classes on post-1945 art. As we all know, classes that began in the traditional way in January went remote in March because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gilliam’s painting remains in place, however, awaiting the return of our students.

Sam Gilliam (b. 1933) has been called one of the great innovators in postwar American painting. Associated with the third wave of the Washington Color School, he broke away from the flatness of the canvas that the color field artists emphasized, folding and crumpling his support to create multiple directions. In doing so, he challenged the boundaries between painting and sculpture. In 1968, Gilliam took a profoundly revolutionary step when he released his abstract paintings from the confines of stretcher bars to hang freely. In a pivotal group exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the following year, he suspended large swathes of color-stained canvases from the walls and ceiling.

“The year 1968 was one of revelation and determination—something was in the air, and it was in that spirit that I did the drape paintings,” Gilliam stated in a 1991 article titled “Solids and Veils” (Art Journal, 10).

Indeed, something was in the air that year: Artists like Gilliam’s mentor, Thomas Downing, as well as Frank Stella, who is represented in W&L’s art collection, were also experimenting with shaping paintings as part of the artistic process. But 1968 was momentous in other ways. The Smithsonian Magazine (Jan/Feb 2018) called it a “seismic year in which movements exploded with force” — the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the civil rights movement, human rights issues and student demonstrations. It was a year that included the Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike, the assassinations of both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, and the Fair Housing Act, among so many other events.

While Gilliam had taken part in the 1963 March on Washington and would go on to help organize the 1971 De Luxe Show in Houston, Texas — one of the first racially integrated exhibitions of contemporary artists in the United States — he was criticized as a Black artist for working abstractly instead of addressing the social and political situation of the day. However, as the L.A.-based David Kordansky Gallery, which today represents Gilliam on the west coast, states on its website: “For an African-American artist in the nation’s capital at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, this was not merely an aesthetic proposition; it was a way of defining art’s role in a society undergoing dramatic change.” In a 2005 exhibition catalog of the Corcoran Gallery, Gilliam himself stated, “Art is at least as important as politics when it comes to creating new ways of thinking about society and moving it forward.”

Gilliam is one of many artists who were acclaimed in the 1960s and 70s, only to recede in celebrity in the next decades. The art market is fickle, but Gilliam had at least two additional strikes against him: his race and his choice to live and work in Washington, D.C., which was not a major art market. In spite of the mercurial art market, Gilliam continued to paint consistently and prolifically, and his popularity has resurged in the last decade. In 1972, he was the first African American artist to be included in the Venice Biennale; He was not invited again until 2017, when he returned as the most prominently placed artist in the international exhibition.

By the 1970s, Gilliam revisited the stretched canvas and continued his lifelong exploration of texture, dimensional direction, materials, processes and always color – continuous riffs on the process of creating art and testing the boundaries between painting and sculpture. His work is as improvisational as jazz, which Gilliam admits was influential. In a 2014 web article on Gilliam for W Magazine, Jim Lewis quoted the artist: “Before painting, there was jazz. I mean cool jazz. Coltrane. Ornette Coleman, the Ayler brothers, Miles Davis. It’s something that was important to my work, it was constant. You listened while you were painting. It made you think that being young wasn’t so bad.”

Other influences on Gilliam include the full pantheon of artists, including Giotto, Rembrandt, Braque and Stella. “I have been holding court with all of painting,” he stated in 1991, singling out the work of the Spanish Baroque artist Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, through which in 1985 he “was able to discover the feel of volumes added to the surface of the picture” (Art Journal, 11). This became apparent in his work in the 1980s and early 1990s, three examples of which are now in the W&L Museums’ collection, thanks to alumnus Rick Kramer. The three pieces together represent a single decade of Gilliam’s interests in different media, formats and processes.

In 2019, Kramer generously donated 41 works of art that were collected over half a century by his parents, Judith and Eugene M. Kramer ’40. In the late 1950s, they were active partners in the Gres Gallery, a significant leader in contemporary art in Washington, D.C., before it closed in 1962. Several pieces in the Kramer collection were purchased at the Gres Gallery, including an early work by Colombian artist Fernando Botero. Through their connections, travels and love of art, the couple amassed a small but significant collection of works by leading artists of the second half of the 20th century across the globe. That collection was initially loaned to the university by Kramer in 2017 for an exhibition titled “A Passion for Art,” which hung through June 2018 in the Kamen Gallery of the Lenfest Center. This was a particularly appropriate venue because Gene Kramer was an active member of the Lenfest Center development committee before his death in 1996.

After the exhibition closed, the collection was used by art classes and has been displayed across campus. The gift significantly expands the university’s collection of art to include more multicultural examples, providing students the opportunity to interact with works by notable Latin American, European, African American and women artists including Rufino Tamayo, Max Ernst, Antoni Tàpies, Sam Gilliam and Grace Hartigan. Gilliam’s work joins that of two other African American artists already represented in the university’s collection: Harlem artist Alvin Hollingsworth, a member of the Spiral Group during the 1960s, and the late Robert Reed, a Charlottesville native and influential teacher who taught for 45 years in the Yale University School of Art and who exhibited in W&L’s duPont Hall in the early 1990s.

Gilliam’s work has a very personal connection to the Kramers. In writing about his parents’ collection, Rick Kramer states: “Some of the artists were longtime friends and others, like Sam Gilliam, became friends.” He said that his parents visited Gilliam’s Washington, D.C., home and studio, as well as the galleries of his wife and manager, Annie Gawlak. The artist also visited the Kramers: “One of Gilliam’s visits to my parents’ apartment was in August 1989. The artist had offered my parents two pieces from his ‘Tulip’ series… in exchange for an investment in the project. My folks were giving me one of the monoprints, so I was present when Gilliam brought the pieces for my parents to see.” Gilliam himself mounted the work they purchased, “Blossoms,” which was a joint venture between Gilliam and artist William Weege, an art professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who had established “Off Jones Road Press,” where they worked, assisted by graduate art students. The construction is an experimental mixed media piece that now hangs in Wilson Hall, serving as a very fine example of collaborative work for our art students.

Kramer recalls Gilliam returning the following year to hang “Chinese,” a small drape painting completed in early 1990, in his parents’ dining room, where the artist bent it around the entrance into the living room. Gilliam returned to reinstall it years later in a new home, and at Kramer’s suggestion, bent a lobe of the painting onto the ceiling. Kramer states that “Chinese” is one of his favorite works of his parents’ collection because “… it has no pre-established configuration and will always bear an imprint of the displayers’ whims and tastes …”

The painting, which is signed, titled and dated on the reverse, is shaped with four lobes, much like a four-leaf clover. It is also slit in several areas, and long strips of canvas, thickly painted and textured, are woven through. In 1991, Gilliam wrote, “The use of the circle was a resolving element in the paintings of the last year and a symbolic one as well, to some degree, suggestive of a sphere.” He continued: “The mystery is over; in the paintings of 1990, the works are in full relief and maintain high sculptural content. The work is presented as a sculpted or faceted object in space. They have been constructed to extend the feeling of the draped painting of 1969. They are objects that abstractly embrace the content of painting and sculpture through solids and veils” (Art Journal, 11).

When I installed the painting this time, I kept Gilliam’s words in mind and looked for inspiration from both his small drape paintings created in the early 1970s, such as “Ruby Light,” and his other work produced around 1990, including “Waking Up.”

The last work by Gilliam in the Kramer collection is an untitled monotype on hand-made paper that is signed and dated 1995. Like other work made at this time, Gilliam cut segments of monotypes into pieces and reassembled them, adding them as collage to the whole, stating “The fracturing presents the wholeness more fully.”

Gilliam continues to paint. His work is found in the collections of major museums throughout the world, including the Tate Modern, London; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. In 2016, the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture commissioned Gilliam to paint a work for the museum’s lobby. Titled “Yet Do I Marvel,” it was inspired by Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen’s work by the same name. In 2018, Gilliam was the subject of a major retrospective at the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland.

In December 2012, the Smithsonian American Art Museum interviewed Gilliam as part of their series titled “Meet the Artist Videos.” In his piece, he states that he was “free to be the artist that he wanted to be” and added at the end: “Every work of art has a moment. Has a time. But, there’s nothing like art. I mean there’s nothing like art.” We hope that the students who experience the Gilliam paintings and other works in the Kramer collection will feel the same: There’s nothing like art.

“Chinese” by Sam Gilliam. Acrylic on shaped canvas. Gift of Richard E. Kramer ’69.

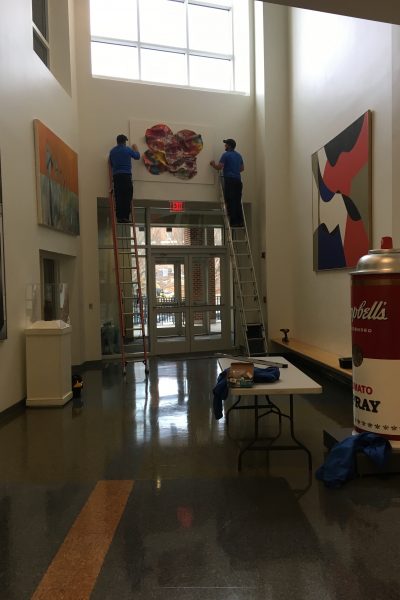

“Chinese” by Sam Gilliam. Acrylic on shaped canvas. Gift of Richard E. Kramer ’69. “Blossoms” by Sam Gilliam installed in Wilson Hall.

“Blossoms” by Sam Gilliam installed in Wilson Hall. “Untitled” by Sam Gilliam. Monotype with collage on irregular hand-made paper. Gift of Richard E. Kramer ’69.

“Untitled” by Sam Gilliam. Monotype with collage on irregular hand-made paper. Gift of Richard E. Kramer ’69. Installing “Chinese” in Wilson Hall in 2019

Installing “Chinese” in Wilson Hall in 2019

You must be logged in to post a comment.